This article was originally published in my column at the Colson Center. It is republished here with permission. For a complete directory of all my Colson Center articles, click here.

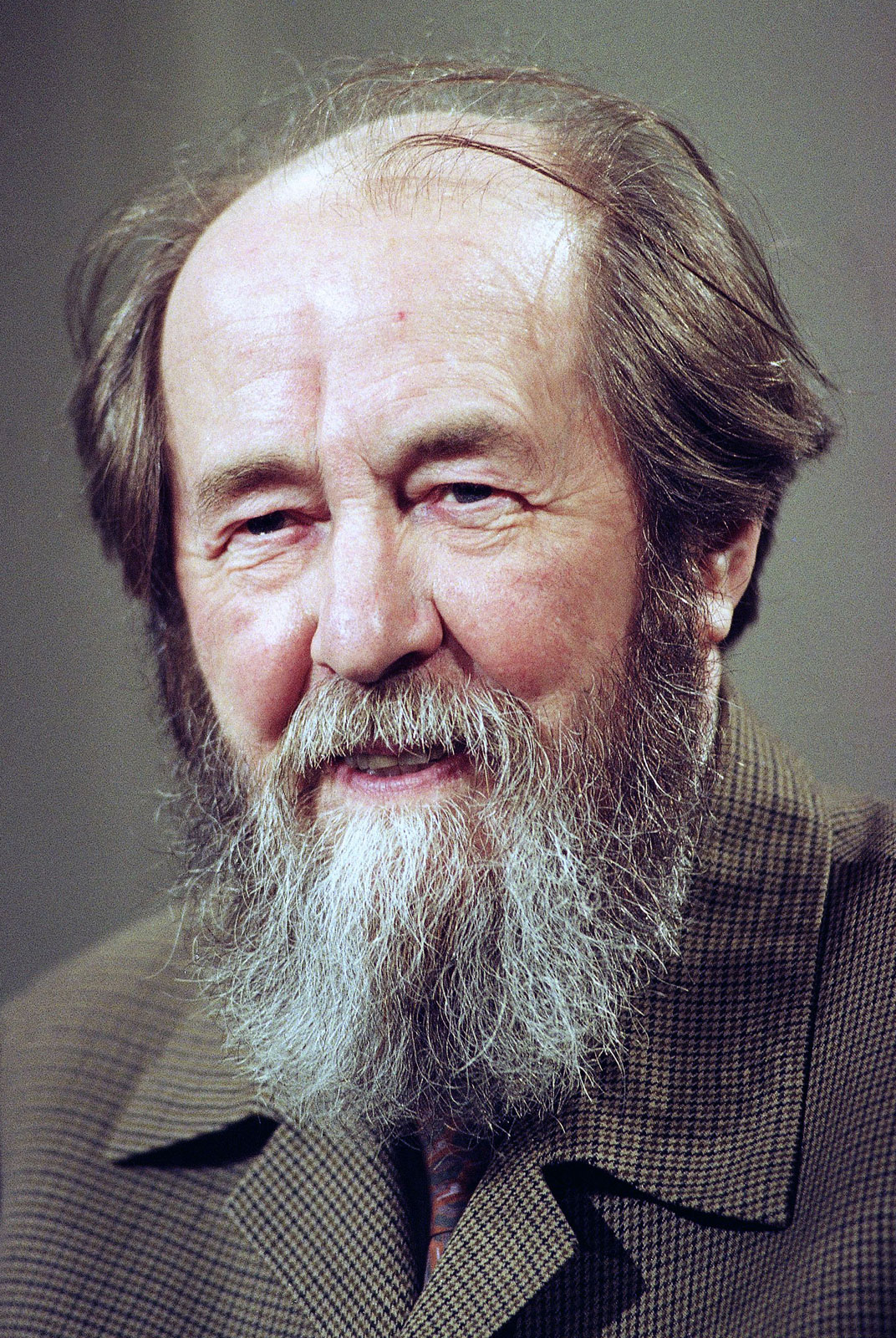

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008) is best remembered for his books on communism – books like the The Gulag Archipelago which ultimately helped to undermine the integrity of the Soviet Union in the eyes of the world.

What is generally less appreciated is that Solzhenitsyn was also a fierce critic of postmodernism.

Don’t be scared off by the term ‘Postmodernism.’ The best way to explain it is against the backdrop of ‘modernism.’ As an ideology, Modernism it is closely aligned with the worldview of secular humanism, which elevates man and his reason to the center of reality. In contrast to the pre-modern worldview, which stressed that all human knowledge is a subset of God’s knowledge, Modernism emphasized that man is at the center of reality and that unaided human reason can discover absolute truth. Solzhenitsyn challenged this view in his Harvard address, claiming that secular humanist ideas were “the mistake” that was “at the root, at the very foundation of thought in modern times.” He continued:

I refer to the prevailing Western view of the world in modern times. I refer to the prevailing Western view of the world which was born in the Renaissance and has found political expression since the Age of Enlightenment. It became the basis for political and social doctrine and could be called rationalistic humanism or humanistic autonomy: the pro-claimed and practiced autonomy of man from any higher force above him. It could also be called anthropocentricity, with man seen as the center of all.

But Solzhenitsyn did not stop by merely confronting Modernism; his message of national repentance also challenged the fashionable Postmodernism of the late 20th and early 21st century.

At the risk of oversimplification, Postmodernism is the worldview which asserts that individuals or groups create truth for themselves. While agreeing with modernism that man is at the center, Postmodernism denies we can discover absolute truth since it rejects the very idea of absolute truth. Within the subjective worldview of the Postmodernist, every person creates meaning for himself. Solzhenitsyn opposed this idea just as fervently as he opposed modernism. He argued that eternal values such as truth and justice do not depend on man for their existence but have an objective existence independent of our minds. As Solzhenitsyn wrote in a samizdat letter while he was still living in the Soviet Union,

“Justice exists, even if there are only a few individuals who recognize it as such…. There is nothing relative about justice just as there is nothing relative about conscience.”

After Solzhenitsyn was deported to the West, he found this message of moral absolutes was just as distasteful to Westerners as it had been to the Soviets. Two days after his Harvard address an editorial in The New York Times declared that Solzhenitsyn was “dangerous” and “a zealot.” His crime? He believed he was “in possession of The Truth.”

Solzhenitsyn’s rejection of Postmodern relativism had direct ramifications for his view of art. In his Nobel Prize lecture, published in 1972, he contrasted two types of artists. “One artist imagines himself the creator of an autonomous spiritual world” while “another artist recognizes above himself a higher power and joyfully works as a humble apprentice under God’s heaven”. Solzhenitsyn urged artists to adopt the latter approach. Reality, including spiritual reality, is not something that we create for ourselves, since it exists external to us. Solzhenitsyn expanded on this in a 1993 speech delivered to the National Arts Club after his acceptance of the Medal of Honor for Literature:

“For a post-modernist the world does not possess values that have reality. He even has an expression for this: ‘the world as text,’ as something secondary, as the text of an author’s work, wherein the primary object of interest is the author himself in his relationship to the work, his own introspections…. A denial of any and all ideals is considered courageous. And in this voluntary self-delusion, ‘post-modernism’ sees itself as the crowning achievement of all previous culture, the final link in its chain…. There is no God, there is no truth, the universe is chaotic, all is relative, ‘the world is text,’ a text any post-modernist is willing to compose. How clamorous it all is, but also – how helpless.