Following the publication earlier this year of three articles with Salvo Magazine about race and identity politics (see here and here and here), I have received questions about racial issues in America, including questions about the way identity politics played out in this year’s civil unrest. Below are my answers to some of the most common questions.

Is America systemically racist?

The word “systemically” makes this question difficult to answer, because many of the people who say that America is systemically racist believe that racism is organically interwoven with the principles on which our nation was founded. To reinforce this narrative, there is a move to date the founding of America, not with the Declaration of Independence om 1776, but 1619 when the first African slaves were brought to the continent. The idea is that America was founded deliberately as a racist nation. Such a theory is problematic on so many levels, and it is very different from simply acknowledging that America has a history of racism.

In 2013, I wrote a series of articles for my former blog showing that the Puritans who first came to these shores used a strange type of crypto-Gnosticism to justify a race-based ideology of supremacy. We can acknowledge these historical facts without making a non sequitur of claiming that racism is systemic. Why? Because America was also founded on Christian and Enlightenment principles (which are not the same, by the way) that existed in tension to these racist philosophies and practices. This uneasy juxtaposition of inconsistent belief systems meant that eventually one would have to triumph over the other. Eventually Christian and Enlightenment ideas about human dignity and equality won out. But this took a long time, and only a decade before I was born, African Americans were still kept from being able to vote in some states, while in many parts of society laws still kept whites and blacks carefully segregated.

The effects of segregation are still felt, particularly in American cities, as David Brooks has pointed out. America’s racist past also exerts an influence on the present in more subtle ways, such as how we conceptualize and think about race.

What do you mean? Can you give me an example of how current conceptualization of race are rooted in America’s racist past?

Well, the ways we define what it means to be “white” or “black” goes back to slavery and the era of the Jim Crow laws. For example, why is it that someone like Barack Obama who had one white parent and one black parent is considered black but not white? Or when corporations or state governments divide people up according to race (as they are increasingly doing), why is it that you often have to be majority white to be considered white yet even the smallest amount of black blood can qualify someone as being black?

The answer to these questions has nothing to do with the science of genetics, but actually goes back to the “one-drop rule” that was used for the benefit of slave owners. In the era of slavery, and later in the era of the Jim Crow laws that officially segregated blacks and whites in a two-tier society, having just one black ancestor disqualified a person from the benefits of being white. For purposes of determining representation in Congress, having one drop of black blood meant that such a person would only qualify as only three-fifths of a person, according to an amendment added to America’s constitution in 1787.

This unfortunate history has left Americans tethered to unscientific ways of conceptualizing race. Why today is it the case that equity policies or affirmative action programs will not consider someone white even in cases where 80% of their ancestors are white? It goes back to America’s racist past and the “one drop rule.”

Where does Christianity fit into all this?

The two-tier society I mentioned earlier kept blacks and white officially separated. This persisted right up through the middle of the twentieth century until Christians began mobilizing themselves to challenge this injustice. Christianity offered 12th century activists a framework for addressing forced segregation, and they used this framework to begin healing the divisions. The role of Christianity in addressing America’s racial divisions was made most explicit by the evangelical pastor, Martin Luther King Jr. King understood that he could appeal to the Christian conscience of Americans when making the case for civil rights. For example, he declared,

“Our method will be that of persuasion, not coercion. We will only say to the people: ‘Let your conscience be your guide.’ Our actions must be guided by the deepest principles of our Christian faith. Love must be our regulating ideal. Once again we must hear the words of Jesus echoing across the centuries: ‘Love your enemies; bless them that curse you, and pray for them that despitefully use you.’ If we fail to do this our protest will end up as a meaningless drama on the stage of history, and its memory will be shrouded with the ugly garments of shame. In spite of mistreatment that we have confronted, we must not become bitter and end up hating our white brothers. As Booker T. Washington said: ‘Let no man pull you down so low as to make you hate him.’ If you will protest courageously and yet with dignity and Christian love, when the history books are written in future generations the historians will have to pause and say, ‘There lived a great people–a black people–who injected new meaning and dignity into the veins of civilization.’ That is our challenge and our overwhelming responsibility.”

Martin Luther King Jr’s Christianity was central to his political agenda because he understood that only Christianity could keep mankind from falling into the primitive pagan condition of fighting amongst different races and tribal divisions.

What do you mean? Can you explain more about what paganism has to do with all this?

In paganism, the division between races, tribes, and people groups came as an inevitable consequence of polytheism. In much of ancient polytheism, each tribe, ethnic group, and nation had their particular god that was locked in a zero-sum conflict for domination with the gods of other nations. I have discussed this in relation to the Ancient Near East politics in my article ‘From Eden to New Creation: Rediscovering God’s Purpose for Planet Earth.’ This basic pagan perspective entailed an unavoidable struggle for domination among the races, as each group sought to use violence to prove that their god was supreme over the other gods. This perspective brought very specific ideas of guilt and expiation, whereby one group could only have their guilt expiated by becoming the target of cathartic rage from their rival group. Accordingly, pagan justice involved one group triumphing over another. Because races and tribes are locked in inevitable conflict, justice for my group can only involve injustice to your group and visa versa. In this primitive perspective, there is no concept of the common good that can unite people across groups.

Various modern revolutionary movements—starting with the French Revolution, through to the various Communist revolutions that occurred throughout the 20th century, right through to the identity politics of the twenty-first century—all have affinity with ancient paganism yet without the same polytheistic underpinnings. The Marxist idea of class struggle, where various classes are locked in a zero-sum struggle for supremacy, or the Fascist idea of an inevitable zero-sum conflict between races, or the postmodern notion that we are all trapped in the micro-narrative of our particular group with no ability to pursue a common good and a common justice, are all simply recapitulations of the basic pagan idea of justice.

How does this pagan idea of justice differ from Christian conceptions?

The doctrine of Christian justice—rooted in the Old Testament but coming into full blossom with the arrival of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost—is aimed at achieving the right ordering of the world and human communities. As Biblical scholar, Fr. Stephen De Young, pointed out earlier this year, God’s justice is one of the divine energies and focuses on the restoration of order, and the ongoing work of creation against the forces of chaos and division. God’s justice brings people of different tribes and nations to live in harmony with His order. By living in harmony with God we are able to live in harmony with one another.

One of the interesting things about America’s civil rights movement is that there was a clear juxtaposition between Christian and pagan conceptions of justice. This can be seen in the competing visions of Martin Luther King Jr. vs. Malcolm X. Malcom X and his “Nation of Islam” movement. For the latter, they advocated civil rights but they did so within the context of a pagan doctrine of justice. For them, white people were an inferior race, created by a mad scientist. But the most relevant aspect of their teaching—at least, as far as our discussion of justice is concerned—is that because the races are locked in inevitable conflict, justice can only be found in one group triumphing over another.

Interestingly, the heirs of the civil rights movement have largely followed the vision of Malcom X rather than Martin Luther King Jr., not in the latter’s theory of racial origins, but in his identity politics. Identity politics is just a resurgence of the pagan notion that different groups are locked in an inevitable zero-sum conflict.

What makes modern identity politics interesting, and hard for many people to understand, is that it combines pagan notions of justice with distorted Christian understandings. This may explain why identity politics is so strong in America, where an emerging paganism has grafted itself onto the residue of Christian assumptions. One author who has helped me to understand this is Joshua Mitchell, author of the book American Awakening: Identity Politics and Other Afflictions of Our Time. Mitchell, who is a Professor of Political Theory at Georgetown University, wrote an article for Providence Magazine showing how identity politics—including the type that arose in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder—has arisen as a confluence of pagan and distorted Christian notions of guilt. From Michell’s article:

The pagan world was the world of many gods, each associated with a people who made payments and sacrifices to their gods. Rousseau wrote in The Social Contract that when pagan nations battled other pagan nations, soldiers did not battle soldiers; rather, gods battled gods. Hence, the cathartic rage of pagan wars.

Christianity toppled the pagan world. The cathartic rage of war, Christians argued, in which one nation purged another, could not solve the problem of man’s stain, which was original, a term we no longer really understand. Original sin means that sin is always already there, prior to a person being born into membership of this nation or that nation. What this means is that blood rage cannot expiate stain; the sins of my people can no longer be purged by cathartic rage toward your people, and vice versa. That is why Rousseau concluded that Christianity had ruined politics, and had produced a civilization of pacifists, whose rage toward other nations could not be enkindled for the purpose of war. If you doubt this, ponder the fact that Christianity developed a “doctrine of just war,” according to which cathartic rage could not be reason enough to go to war.

Against the backdrop of pagan history, Christianity is revolutionary, not evolutionary. The evolution of paganism, had it occurred, would have brought about novel forms of cathartic rage toward other peoples. Christianity declared that no matter what evolutionary “advance” paganism might bring, it could never adequately address the problem of man’s stain. Christianity was revolutionary because it declared that we must look elsewhere than toward others, with cathartic rage, to expiate our stains. That “elsewhere” is divine, not mortal. Only through Christ, the divine scapegoat, who “takes upon himself the sins of the world” (John 1:29), can man be cleansed.

If Christianity is receding, then we will likely see the return to the pagan understanding that peoples are the proper objects of cathartic rage. That is a sobering truth, which defenders of secularism deny. The real alternatives might not be Christianity or secularism, but rather revelation or paganism. Should we return to paganism, one people will seek to cleanse themselves of stain by venting their cathartic rage on another people. The war between the gods of the nations would resume in full. The “blood and soil” nationalism that is straining to emerge on the Alt-Right is a witness to the reemergence of this pagan view, which is contemptuous of Christianity’s counter-claim, and always will be. What counts in the pagan world of blood is not me, the “person,” but the people of which I am but a representative…

Liberalism, now under fire from so many quarters, is inconceivable without the backdrop of the Christian claim about persons. That is why liberalism can say without embarrassment that citizens who live in the bordered community that their state recognizes and enforces are equal under the law, that each of their votes counts, that each of their preferences count. Because of Christianity, the liberal state—rather than the national community—becomes thinkable. The question for America is simply this: can it become a liberal state, or will it become a battleground of national communities?

George Floyd’s death and the violent aftermath has prompted questions about what sort of world we live in. If we live in a liberal world that Christianity makes possible, George Floyd’s death is a singular transgression, which law can and will punish. George Floyd was a person. So, too, was the policeman who killed him. Persons are protected by the law; and those persons granted policing authority by the liberal state have a somber responsibility to use their vested authority to protect persons rather than to harm them. That is why the death of a civilian by police hands will always attract attention. The same original sin that is the basis for establishing the category of persons is also the reason why a policing force must be vigilantly watched.

What if we do not live in a liberal world that Christianity makes possible? What if, under the pretext of liberalism and Christianity, America is still pagan? That is, what if America has always been a white nation, and still is? This is the position of many on the American left today. It is a position that holds that the black man, George Floyd, and the white police officer responsible for his death, are representatives of blood nations, not singular persons. The murder of one by the other is representative of the collective murder of one people by the other. American law cannot bring about justice, because each blood nation has its own justice, from which marginalized blood nations can never benefit. American law is white law. Street vengeance, therefore, is the only recourse—whether we call them protests or riots. White people must die, as a just exchange for the black people who have died.

This pagan view certainly informs many analyses of America. What is striking, however, is that intermixed with this view is also a Christian claim that each individual person who is a member of the transgressive people should feel deep personal guilt about what has happened. In a purely pagan world, this would be unthinkable. Once a blood sacrifice was made, the score would be settled. In America today, there are some who are scoring accounts in this way; but what has been most remarkable about the aftermath of George Floyd’s death has been the mix of pagan blood accounting and Christian guilt, which has taken the form of a kind of racial contrition, in which apologies are offered to members of the black nation by whites for their complicity in murder, because they are members of a white nation. This intermixed pagan and Christian logic is what we are seeing play out in America today: persons who, on liberal grounds, are not guilty of a crime, confess their guilty complicity in the crime that through their proxy, a white policeman, they have committed.

The problem of America—and not of America alone—is that she lies somewhere between paganism and Christianity. The Christian hope that man treat his fellow man as a person was first violated by the legalized slavery of one race. We have yet to fully recover. As Tocqueville put it in Democracy in America, “Christianity declared the equality of all men; and yet American Christians introduced slavery into their country.” America: the country where Christianity held sway, and where Christians betrayed what Christianity proclaimed.

How, then, shall we proceed? Onward or backward. A return to paganism would spare us from the embarrassing Christian postulate that all the guilty-before-God descendants of Adam are persons, to be treated equally before the law. Pagan blood vengeance, we would contentedly conclude, is the primordial truth of man—therefore let us unleash the cathartic rage that dwells in every heart. If a man of one race is killed, blood payment is due; the score must be settled; persons must be sacrificed so that the idol of bloodline, of “identity,” can be appeased.

Alternatively, there is the Christian way forward, through which we will recognize the singular person of George Floyd, the transgression that ended his life, and the law through which man does what he can to bring about justice, in a broken world that God alone can heal.

Americans today are torn between these two distinctly different understandings of what justice entails: pagan blood payment between peoples, which treats persons as mere proxies; or liberal justice, whose foundation is, finally, the Christian understanding of persons. Paganism, let us remember, is the natural condition of man, the condition for which there is no remedy without the divine antidote that breaks in upon the natural world and informs us that justice entails more than cathartic rage that settles scores. An observer with a trained eye will see in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death an America that cannot decide between pagan justice and liberal justice, and which has settled into a dangerous and unstable intermediate arrangement having elements of both. Logic would dictate that either we go back to guiltless paganism or go forward to guilt-ridden, person-centered, liberalism. We have guilt-ridden paganism instead, another name for which is identity politics.

Could you give us a brief rundown of identity politics?

I wrote about identity politics in chapter 16 of my book Saints and Scoundrels. Identity politics is both descriptive and prescriptive. It is a theory for viewing how society organizes itself, as well as an agenda for political action. Descriptively, it tells us that a person’s particular group (i.e., African Americans, feminism, LGBTQ, etc.) is of such paramount importance that group-identity forms the lens through which to view political issues or make policy decisions. Prescriptively, identify politics is the theory that these group-based worldviews are appropriate, inevitable, inescapable, and normative.

Politicians who have succumbed to identity politics see little problem pigeon-holing individuals into belief-patterns based on their group identity, on the assumption that someone’s skin color, ethnic origin, gender, or sexual preferences ought to determine their political beliefs. For example, last year Democrat Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts went on television and announced,

“We don’t need any more brown faces that don’t want to be a brown voice. We don’t need black faces that don’t want to be a black voice. We don’t need Muslims that don’t want to be a Muslim voice. We don’t need queers that don’t want to be a queer voice.”

Pressley was not an isolated case. As I pointed out earlier this year in an article for Salvo about Joe Biden, pigeon-holing people based on race is now routine within corporate America thanks to equity policies. Moreover, once someone has been pigeon-holed by their race, then you can dismiss that person’s views, not based on the truth or falsity of the ideas, but because of the race of the person holding those views (i.e., “a white person shouldn’t think that,” or “that belief is inappropriate for a brown woman,” etc.) We saw this played out in the recent riots, where some people alleged that for white person to object to rioting is itself a racist act. Notice that the argument is not that white person’s ideas are false, but inappropriate for a white person.

Pigeon-holing people based on race is also seen in the growing insistence that white people must prove their non-racism in actions that demonstrate shame for “whiteness.” Some districts are even making this a prerequisite to employment.

As the concept of “racism” is being weaponized by identarian-leftists, the term itself is in danger of losing objective coherence. We see this happening in the fact that many people do not even know anymore what racism actually is. Is in-group preference racist? Are racial generations racist? Is advocating for a color-blind state racist? Is the bell curve racist? Is the bell curve racists if it’s false but not if it’s true? Is it racist to believe that America was founded in 1776? Am I racist if I share BLM’s concern about police brutality yet dissent from the other political agendas that have become tethered to the movement? These are all important questions, and yet we cannot have a rational discussion about these and other questions (at least, not at the level of public national conversation) now that identity politics has weaponized the entire discourse.

Where did identity politics come from?

I already mentioned the ancient pagan pedigree to identity politics. But the modern versions of identity politics draw heavily on certain variants of postmodernism which sees all of us trapped in micronarratives that define us and prevent intelligible interaction across our ideological divides. I have traced the history of these postmodern ideas in my article, ‘John Milbank and the Life of Pi.’ The bottom line is that, as in ancient paganism, society becomes reduced to a battleground among competing among groups who are locked in a zero-sum battle for power.

In addition to its postmodern pedigree, identity politics also draws on Social Marxism, which has been a growing movement in the political left ever since Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937), and later the Frankfurt School, reinterpreted Marxism to no longer be about economics but about power. Social Marxism no longer divides society into economic classes, such as proletariats and bourgeoisie, but instead they divide society into various group identities, such as race, gender, sexuality, religion, etc. These oppressed groups are encouraged to identify as victims, and then to seek ascendency via a redistribution of cultural power. This means that all of culture, academia, art, media—in short, all aspects of society—become politicized in the zero-sum contest between competing groups.

A toxic mix of identity politics, postmodernism, and social Marxism, now dominates the humanities departments of most universities. In most universities now, it is impossible to look at history, religion, literature, culture, art, and numerous other disciplines, without these fields becoming fodder for victimology studies. Each group that is seeking power will give their own interpretation of, say, English literature (to give one example), and so you can read a text through feminist theory, or environmentalist theory, or queer theory, and so forth. Having been primed by postmodernism to believe that we are all trapped in our own ideological tribes and cannot communicate outside our own biases, it doesn’t strike us amiss to have whole disciplines fracturing into a multiplicity of micro-narratives and victimology studies.

Identity politics, though promoted by groups that should have a strong interest in racial healing (such as the Black Lives Matter movement), actually ends up undermining any basis for racial healing, since identity politics tethers all discussion of race to a zero-sum contest for power. Curiously, those who have tried to pursue racial healing outside the framework of identity politics, such as the black musician, Daryl Davis, are opposed by members of BLM.

In the end, I don’t think I’m exaggerating to say that identity politics is even more dangerous than the United States if we were invaded by a foreign power. This is because identity politics is gradually undermining how we view freedom itself. If we were fighting for our liberty against an occupying power, we would still likely understand what it means to be free; however, what identity politics does is to confuse the very idea of freedom itself.

How does identity politics undermine our understanding of freedom?

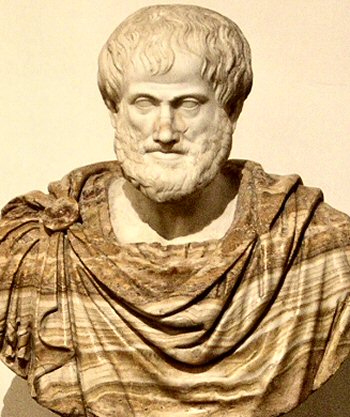

Identity politics is fundamentally at odds with classical and Christian notions of freedom. In this older tradition, going back to Aristotle and finding expression in Christian political thought, liberty is the freedom to pursue the good without external obstacles or restraints. For an organism – whether an individual, a city, or a nation – to be “free” is for that organism to have the liberty to realize its proper telos and thus to flourish in the good appropriate to it. In the case of nation states, the telos towards which it is oriented is the common good of all people, not the good of one particular person or group.

In this classical understanding of freedom, obstacles that prevent a nation from realizing the common good – whether floods or foreign invasion – can rightly be said to threaten the nation’s freedom. Similarly, policies that privilege certain groups in a way that compromises the common good of all, can also be rightly categorized as antithetical to the values of freedom.

Identity politics, and the progressivist philosophy that forms its larger backdrop, is just such a threat to freedom, for it eschews the pursuit of a good common to all in favor of only what is good for my group. Such a philosophy does not even recognize that the common good is a legitimate telos towards which the state ought to be oriented. Bradley Birzer, who holds the Russell Amos Kirk Chair in History at Hillsdale College, wrote an article for The American Conservative where he described the way leftism challenges the notion of common good that is central to American concepts of liberty:

[T]he progressive vision demands conflict. That is, in its understanding, history is made up of winners and losers. This flies directly against the long tradition of republican and Judeo-Christian thought that calls for the “common good” of the res publica, not the greater good of those who might be victorious. In the greater part of the Western tradition, at least up through the writings of Nicolo Machiavelli, the most important intellects recognized the flaws or fallenness of man, noting that power must be divided and guarded against. The progressives, wittingly or not, embraced the idea that those with established power should be taken down by others with power, thus creating a third and new power, itself soon to be the establishment and challenged. As such, the guiding force of society is might, not justice. In the res publica, ideally, each gives up some of his rights and treasure for the benefit of the whole. Thus, while each suffers some, the whole benefits mightily. No such rules or restraints govern the progressive vision. Truly it is a comparative: the greater good, not the common good. Power thus replaces love.

Although identity politics has largely been limited to the political left, it has seen a precipitous rise among right-wingers in the United States since around the middle of the last decade. I discussed this in my article ‘The Republican Retreat to Identity Politics.’ Whereas left-wing identity politics owes itself to post-war social Marxism, with roots in ancient paganism, the new right-wing identity politics comes from the long re-mapping of American conservatism in the post-cold war era. This new left-wing pseudo-conservatism (and I call it pseudo-conservatism since the idea of conservative identity politics is, strictly speaking, an oxymoron), has recently been fueled by the rise of left-wing identity politics, unsustainable immigration, political correctness, and virulent attacks against Judeo-Christian culture.

What can we do about this? Is there any hope?

Unfortunately, that will have to be the topic of a follow-up post.

Further Reading