Since 2017, I have been receiving inquiries about what I think of the preacher of hate known as “Brother Nathanael.” An internet celebrity whose popularity has mushroomed since 2020, Brother Nathanael now wields considerable influence through his online ministry. His reach extends far beyond the Pacific Northwest as hundreds of thousands now follow his hate-filled rants such as this and this. Before he got kicked off of YouTube, his videos reached views in the millions.

In his online tirades, Brother Nathanael mixes Christianity with what he calls the “nationalist hopes” of “the white Christian man.” He is very forthright in what this nationalism should involve, arguing for the violent overthrow of government, the establishment of a right-wing military dictatorship, and mass executions against his political enemies, particularly liberals, Jews, globalists, and anti-Trumpers.

Brother Nathanael represents, in a particularly distilled and extreme form, a type of right-wing identity politics that has been gaining traction in the last eight years and which I have addressed elsewhere (see here and here and here and here and here). But whereas other extremist voices typically offer argumentation and the pretense of reasoned analysis, Brother Nathanael’s modus operandi rarely rises above scoffing, scorn, and racial slurs.

Brother Nathanael also has channels on multiple platforms where he teaches theology, although in that case his rhetorical jabs are targeted against anyone who isn’t Eastern Orthodox. His theology channel is so dark that I am not linking to it here for fear of giving ammunition to the enemies of the Church. But it is worth noting that his online Bible teaching, accompanied with in-person classes at various churches and groups throughout the Pacific Northwest, is one of the reasons his race-based theology is so popular. If he were merely preaching political extremism, he would be lost in the online sea amid hundreds of other wackos. But he has been able to create a niche following because he offers a complete package: a theological-political-cultural-racial worldview.

But is it True?

Because Brother Nathanael appeals to people’s passions, particularly paranoia and hatred of Jews, few people stop to ask if what he teaches is actually true? More specifically, given that Brother Nathanael is Eastern Orthodox, it is worthwhile to ask: does Brother Nathanael’s racial political theories accurately represent Orthodox theology?

This is a difficult question because pastors understandably shy away from discussion of politics. As I pointed out in an article about discernment earlier this year, many pastors are afraid to engage in political questions because this is an area where human passions are rampant. But this only creates space for toxic political theories to emerge. Believing that politics is just a matter of opinion, biases, and passions, many faithful pastors and priests don’t even realize that the Church has a political theology that can be used to counter the toxic theories of teachers like Brother Nathanael. Let’s look closer at this tradition of political theology.

The Incarnation and Orthodox Geopolitics

Orthodox political theology starts with the Incarnation. Prior to this momentous event when God became man, false gods and fallen angels controlled heavenly bodies and nations, and thus were able to influence human events. These entities were originally part of the divine council who shared in God’s rulership, but after becoming rebellious they used their positions to wreck havoc on the earth. (To learn more about this, listen to the Lord of the Spirits podcast or read my article about this from last year.) We see this havoc in the political landscape of the Ancient Near East, where each tribe, nation or people group believed that their particular god was locked in a winner-take-all conflict with the gods of the other tribes and nations. The conflict between the races was thought to mirror the conflict in heaven, where various gods vied with each other for supremacy. That is why there were spiritual implications whenever God’s people in the Old Testament lost in battle.

With all people groups locked in a never-ending conflict, it followed that justice for one group could only be obtained by injustice against another group. A group perceived to be guilty could only expiate that guilt by becoming the target of cathartic rage and scapegoating from a rival group. This primitive perspective had no concept of the common good that could unite people across groups, nor did it provide a normative framework for solving disputes. Instead rival peoples were treated as sub-human, often believed to be incapable of reason and intellectual virtue. Thus, politics in the ancient world could never rise above raw power and hate.

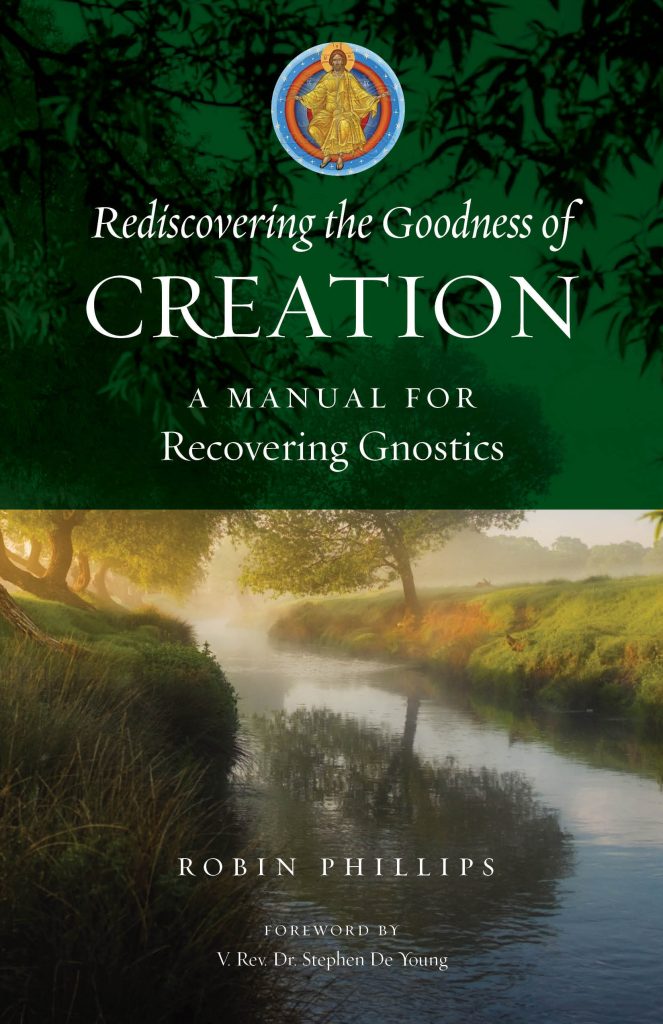

At the Incarnation, Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Ascension, the principalities and powers that war in the heavens suffered catastrophic defeat. Rebellious entities were cast out of the divine council, and Christ reclaimed the thrones, dominions, and principalities for Yahweh, filling these positions with saints and faithful angels. This means that dark powers no longer have authority over specific nations and geographical areas. Christ now rules the nations and His rulership is mediated through his saints. This has massive political implications, many of which I discussed in chapter 10 of my recent book Rediscovering the Goodness of Creation. One such implication – particularly relevant to the present discussion – is that it is no longer meaningful to view geopolitical problems as primarily a matter of group conflict. Let’s unpack that.

Even after the incarnation, the world continues to be a theater of much evil. Yet between the inauguration and consummation of Christ’s kingdom, the residual conflict is characterized by what St. Augustine called the City of God and the City of Man. The City of God represents Christ’s kingdom on earth; the City of Man represents the demonic resistance to Christ’s kingdom by the shadowy forces who were overthrown at his victory. Human beings participate in these cities, depending on the orientation of their love. While entire nations and people groups sometimes let themselves be controlled by the forces advancing the City of Man, the terms of engagement are different than before the incarnation. No longer is justice achieved by giving vent to cathartic rage against guilty groups. No longer is truth served through a process of scapegoating that would seek to explain the complexity of the world’s problems by blaming a single group or religion.

Moreover, because Christ took on all of humanity, and not just one particular race, it follows that the modus operandi for communication need no longer be the intractable us-against-them discourse of the ancient world; instead, Christians can embrace reason-based debate that honors all people as capable of reason and intellectual virtue. This understanding led to a rich tradition of Christian political theology in east and west, including well-developed and nuanced ways for understanding the conflict between the City of Man and the City of God – ways that moved beyond the hate-based tropes of the ancient world.

Turning the Clock Back on the Incarnation

Brother Nathanael seems not to have sufficiently accounted for the Incarnation. Like someone living in the Ancient Near East before Christ, he perceives national and geopolitical disputes as primarily a matter of group-based conflict. He has created a worldview in which all the world’s problems are the fault of Jews, who he sees as the driving force behind globalism, leftism, and basically everything that is wrong in contemporary American society. The purpose of his online rants and musical performances is not to make us more thoughtful, but to stir up feelings of frustration, rage, and hate against these groups.

One of the ways Brother Nathanael fuels rage is by continual stereotyping, scapegoating, fear-mongering, and witch-hunting against Jews and the other groups he hates. This, in turn, fuels a type of right-wing identity politics that has been steadily growing over the last ten years, which tends to interpret all current events through the lens of group-based victim narratives. It’s easy enough for conservatives to be alert to the problem of identity politics when the source is from the left. For example, when we see woke pundits pigeon-holing people based on race, or leveraging group-based victim narratives for political gain, we naturally recoil. And yet Brother Nathanael is doing the same from a right-wing perspective, even using some of the same ideologies and tactics present among advocates of critical race theory.

But this merely turns the clock back on the Incarnation and Pentecost, as if the intractable us-against-them discourse of the ancient world (now embraced as normative by various woke and postmodern theories) is a condition Christians should flow with and even seek to supercharge. Of course, if you believe there is something cathartic in venting rage against offender groups, then Brother Nathanael’s website or his BitChute channel is the place to go. If you believes that our political problems can be solved by a rhetoric of contempt, and that our public discourse is necessarily a theatre of incomprehensibility between waring ideological tribes, that in the end all conflict boils down to race, then Brother Nathanael is your man. If you believe that Christians should abandon St. Paul’s advice about striving to live respectfully and peaceably with our enemies, then you should donate to the Brother Nathanael Foundation.

Is there a better way? What might a politics rooted in Incarnation and Pentecost look like? I offer some tentative answers to this question in my book, Rediscovering the Goodness of Creation. From chapter 10:

“

Living in harmony with God empowers different peoples to live in harmony with each another and the natural world, at least in principle. Thus, God’s Kingdom is intensely political, for it offers a mandate that promotes flourishing in the entire earth, including the body politic. Crucially, however, the politics of God’s Kingdom do not align with specific parties, candidates, or platforms; rather, God’s Kingdom is countercultural, offering a way of being human that runs contrary to the spirit of this age. God’s Kingdom shows us how to organize human affairs, including civil society, based on the virtues of justice, truth, and love rather than the mere exercise of power.”

Let’s think about this last line: justice, truth, and love rather than the mere exercise of power. We might debate what this involves, but if you think these kingdom priorities are consistent with Brother Nathanael’s call for a military dictatorship dealing out mass executions to Jews and Democrats, and if you think these kingdom priorities are consistent with a rhetoric of contempt, scorn, and scoffing, then you don’t need a theologian but a therapist.

Conclusion

In this article I tried to assess the race-based based political theories of Brother Nathanael. I suggested that his theories of geopolitical conflict make the same mistake as wokeness by resuscitating the hate-based tropes of the ancient world, which would recast all problems through the lens of group conflict. Through a hate-based modus operandi that includes scoffing, mockery, scorn, and racial pejoratives, Brother Nathanael offers an online space for people seeking cathartic rage against offender groups, whether immigrants, liberals, or Jews. But this, I have suggested, fails to do justice to the incarnation in numerous specific ways that I have tried to outline.

In a future post, we will continue exploring Brother Nathanael, but from the perspective of the epistemic virtues. Because Christianity is incarnational, and that means that we do not simply assess teachings rationalistically; rather, we must also assess if a pattern of messaging is virtuous. If it turns out that Brother Nathanael is deficient in the epistemic virtues, then that throws into question his reliability as an interpreter of current events. But that is the topic of my follow-up post, “Assessing Brother Nathanael’s Messaging in Light of the Epistemic Virtues” and my full Brother Nathanael Archives.

Update on June 22, 2024

Today, as we prepare to celebrate Orthodox Pentecost, I return to this article for an update.

Just as online satanism often ramps up around the time of Easter, so on the eve of Pentecost (the holiday where we celebrate the coming together of all tribes and nations in the church), Brother Nathanael has taken his divisive us-vs-them racial agenda to new levels of heterodoxy.

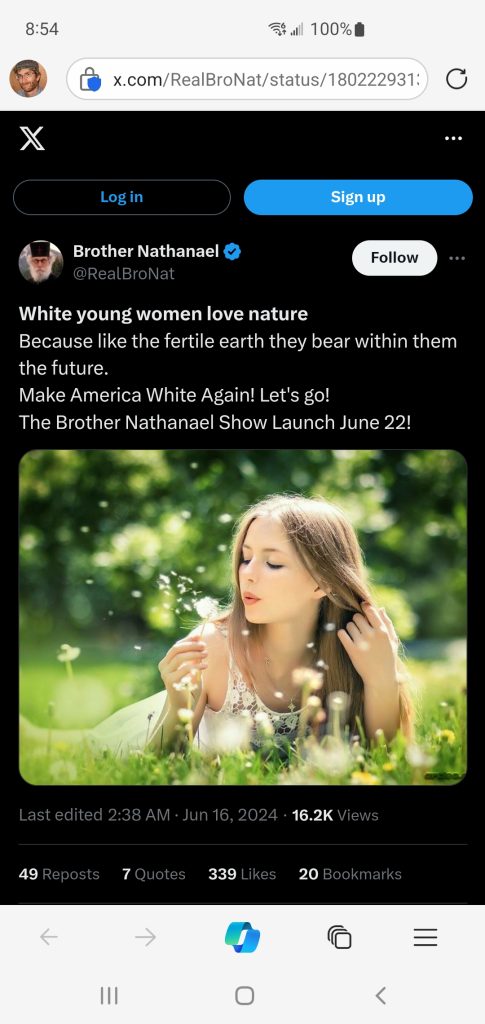

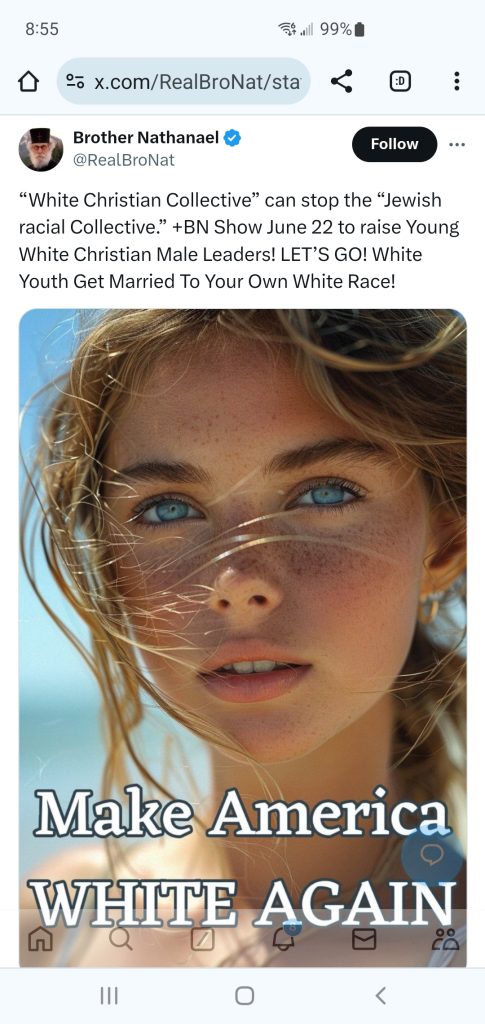

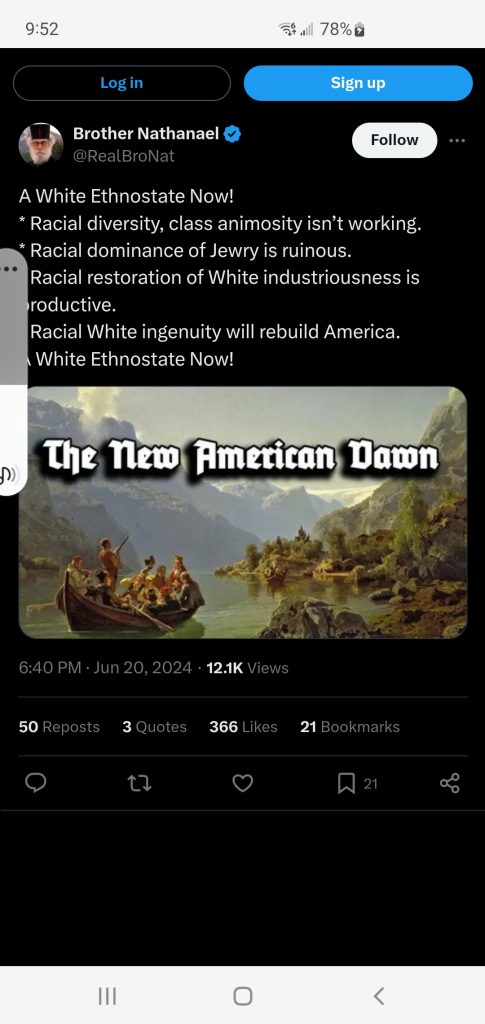

Today he announced on Twitter that he is starting “The Brother Nathanael Show” with the purpose to “Make America White Again.” Powered by a new website, the show will continue scapegoating and witch-hunting people with the wrong skin-color. How do I know the show will do this? Because in the runup to the launch, Brother Nathanael has been marketing it with a string of propaganda borrowed from the Nazi playbook. This propaganda features images of white female models alongside calls for racial purity, admonitions against interracial marriage, a string of tweets shaming mixed-race couples, and calls for the establishment of “a White Ethnostate.”

I’ll leave you with a sampling of some of the images advertising his new venture, just so you know I’m not making it up.

Further Reading

- Antisemitism and the Gospel

- America and the Collapse of Politics

- Epistemic Virtue, Discernment, and Buck Johnson’s Podcast

- Racism and Identity Politics in America Today

- How COVID-19 Led to a Spiritual Pandemic

- Right-Wing Violence and the Trump Personality Cult

- The Republican Retreat to Identity Politics