In an interview for NBC’s TODAY, Tom Hanks talked about his role in the film A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood. Sharing what he had learned from playing children’s TV celebrity Fred Rogers (1928-2003), Hanks summed it up by commenting, “It’s good to talk, it’s good to share the things we feel.”

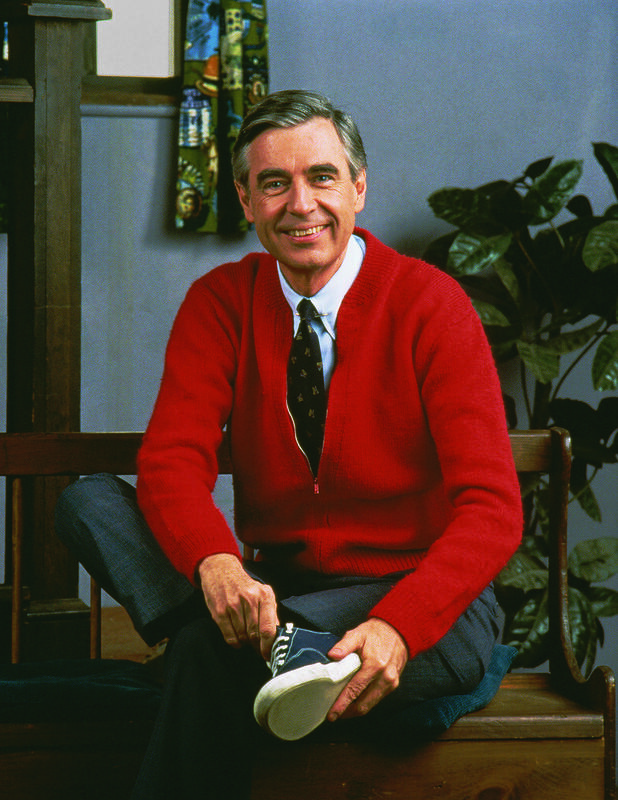

For many children in the last half of the twentieth century, watching Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood may have been the only place they encountered the idea that emotions are okay.

“My parents did not always look favorably on the expression of emotion,” one lady told me. “But when I watched Mister Roger’s Neighborhood, I got a different message. I learned that it’s okay to name my feelings. Feelings can be named and managed.”

Mr. Rogers wasn’t afraid to broach difficult subjects with children, including talking about feelings that are messy and complex. In various ways, he was a model of masculine vulnerability and strength.

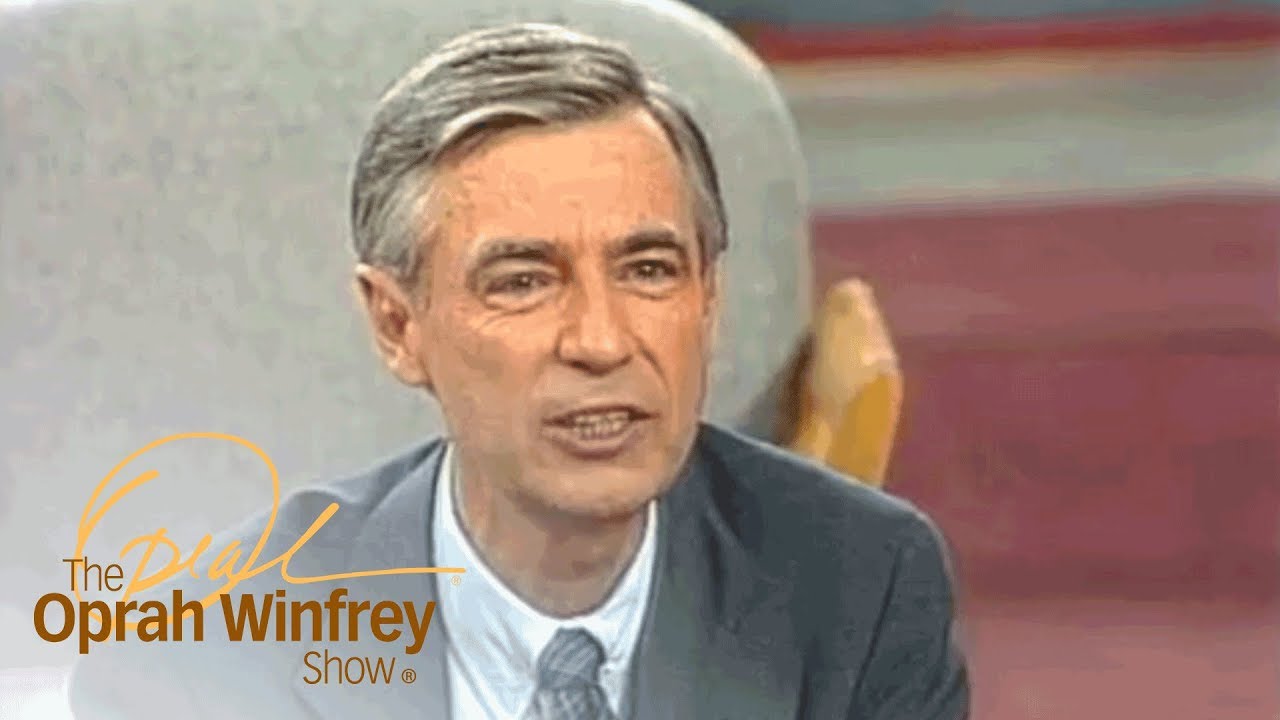

In 1969 Rogers testified before the Senate Subcommittee on Communications to ask for funding for public broadcasting. This was one of the most remarkable speeches ever delivered because Rogers brought discussion of emotion and vulnerability into congress. He talked to the senators about feelings, including sharing a song he wrote about self-control, and opening up about his own feelings of concern about the violence children were exposed to on television. “I think that it’s much more dramatic that two men could be working out their feelings of anger—much more dramatic—than showing of gunfire. I’m constantly concerned about what our children are seeing.” As Rogers continued talking about his vision for children’s television, the tough and abrasive Subcommittee chairman, Senator John Pastore, warmed up to Rogers and even began sharing his own feelings. The point here is not that I agree with Rogers about using tax-payers’ money for to finance public television, but that his gentleness, vulnerability, and EQ were contagious.

When I was a little boy and watched Mister Rogers Neighborhood, I always felt that he was talking directly to me, that he was giving me permission to be myself. People who knew Rogers said that he had this same manner off-set: he made each person feel like they were the most special person in the world, and that he had all the time in the world to listen to him or her.

Tom Hanks observed that Mr Rogers’ vulnerability runs counter to the cynicism of our contemporary culture, a point I have also had occasion to observe. “No one wants to lead with vulnerability,” Hanks remarked. “We all want to be met with compassion but in order to do that you actually do have to lead with some brand of vulnerability.”

Things have moved on since the late 60’s when Mister Rogers Neighborhood began. Getting in touch with our feelings has now become cool, as has vulnerability. Countless self-help books laud the expression of feelings as the key to authenticity and self-actualization. No one embodies this ethic better than Oprah Winfrey, whose show offers viewers a feast of feelings of all sorts, from sympathy to rage to disgust. Oprah has spoken of feelings as “your GPS system for life”, adding “follow your feelings. If it feels right, move forward.”

Some might be tempted to see Rogers as part of this larger cult of feelings-worship. Yet there was one thing that made Fred Rogers different to Oprah and the self-help gurus who followed in his wake. Fred Rogers taught children that learning to be present with their feelings is only one half of the picture. The reason it is important to identify our feelings is so that we can work to manage and transform our emotions. For Rogers, raw feeling was not the goal, but rightly-ordered feelings, and correct choices in response to those feelings. As an example of this, consider the song he composed “What Do You Do With the Mad That You Feel?.” The song opens by helping children talk about their feelings of anger.

What do you do with the mad that you feel

When you feel so mad you could bite?

When the whole wide world seems oh, so wrong…

And nothing you do seems very right?

In these words, Mr. Rogers invited his viewers to name and own their emotions instead of just keeping them bottled up inside. Having studied child psychology, he was aware that being able to talk about how you feel is important for wholeness and emotional health. But that is not where he stopped. In the song’s last two verses, he urged boys and girls not to be defined by their negative emotions, but instead to replace these emotions with a positive feeling of personal responsibility as they press forward to maturity as a man or woman.

It’s great to be able to stop

When you’ve planned a thing that’s wrong,

And be able to do something else instead

And think this song:I can stop when I want to

Can stop when I wish

I can stop, stop, stop any time.

And what a good feeling to feel like this

And know that the feeling is really mine.

Know that there’s something deep inside

That helps us become what we can.

For a girl can be someday a woman

And a boy can be someday a man.

What Rogers was doing in this song—and many others like it—was helping children reframe their darker feelings, moving to rightly-ordered inner states like self-control and personal responsibility. This is also a move that we frequently find in the Psalms, as I discussed in my post ‘Listen to Your Feelings – they might have something important to tell you.’ Consider how many Psalms begin by naming the darker emotions, but then progress towards a healthy management of those feelings based on God’s work and His promises.

Discoveries in emotional intelligence (or “EQ” as it is sometimes called), have found that there is a link between identifying or listening to our emotions, on the one hand, and being able properly to manage our feelings, on the other. According to all the latest science, it is very difficult to interact responsibly with our emotions, or with the emotions of others, if we have not first learned to acknowledge and be mindful of our inner emotional states. Fred Rogers helped his viewers with both of these aspects. He helped his viewers to notice what they were feeling inside, and then to use that information to make responsible choices in how they dealt with those emotions. Above all, he never encouraged children to think of themselves as simply a victim of unpleasant feelings or of the experiences that caused those emotions.

By contrast, many self-help gurus simply leave us stranded in immature feelings like narcissism and victimhood. This is where Rogers differs significantly from Winfrey. In an article for The New Republic in 2006, Lee Siegel identified some of the ways that Oprah was promoting a culture of victimization.

“Her ‘victimized’ viewers–not all her viewers, to be sure–are simply people who have been hurt and have nothing to guide them and nowhere to turn…. Oprah’s public narrative of private victimization shadows every moment of the narratives that get spun on her show. …

With Oprah’s message of victimization comes a great hospitality to feeling, but feeling as an end in itself without any objective context for discriminating between mature or immature feelings, or between ordered and disordered emotional expression. To quote again from Siegel,

We weep and empathize with the self-destructive mother, we weep and empathize with Sidney Poitier, we weep and empathize with the young woman dying of anorexia, we weep and empathize with Teri Hatcher, we weep and empathize with the girl with the disfigured face, we weep and empathize with the grateful recipients of Oprah’s gift of a new car to every member of one lucky audience, we weep and empathize with the woman burned beyond recognition by her vicious husband. In the end, like the melting vision of tearing eyes, the situations blur into each other without distinction. They are all relative to your own experience of watching them. The fungibility of feeling is really a reduction of all experience to the effect it has on your own quality of feeling.

Not so with Mr. Rogers. Yes, he was someone people could feel safe with in all their vulnerability and pain, but he was also someone who made you want to strive for something higher. An ordained Presbyterian minister, his goal was always to help people towards spiritual and psychological maturity. That is why he not only gave puppet shows for children, but also taught courses about discipline for parents.

Oprah and Rogers both took seriously the fact that human beings feel deeply, but Oprah misdirects the emotive impulse. By promoting a type of commodification of emotion within the context of entertainment, Oprah gives us an outlet for feeling without growth, a way to experience emotion without being challenged to move into deeper self-knowledge or constructive action. Where Rogers helped us focus on our feelings as a means to personal maturity, Oprah helps us focus on our feelings as an end in itself within the larger matrix of autonomous self-actualization.

Oprah’s narcissistic exploitation of feelings reminds us of St. Augustine’s critique of the theater in The Confessions. Reflecting on his wayward youth, he said that the simulated grief, compassion, and affections he experienced at the theater “would not probe into me too deeply,” and “affected only the surface of my emotion.” St. Augustine realized that this self-referential indulging in “the surface…emotion” masked over his spiritual need to go deeper that could only be fully realized in repentance.

Using St. Augustine’s categories, we could say that Oprah traffics in the surface of our emotion, whereas Fred Rogers encouraged us to go deeper. True, his spirituality was of a rather thin sort, and while he never went as deep as St. Augustine in showing that true emotional healing can only be found in repentance, he still offered a message that our world desperately needs to hear: it’s good to slow down, it’s good to talk, it’s good to listen to each other, and it’s good to notice how we’re feeling so we can make responsible choices for ourselves, for others, and for the world.

Further Reading

- The Virtue of Vulnerability in an Age of Sentimentalism, Stoicism and Cynicism

- Listen to Your Feelings – they might have something important to tell you

- Series on Attentiveness

- How Jordan Peterson and Kevin Costner Taught me the Meaning of Courage

- Beautifying Brokenness: How God Works With Weakness and Why it’s Okay to be You

- Self-Esteem, Self-Compassion, and Self-Love