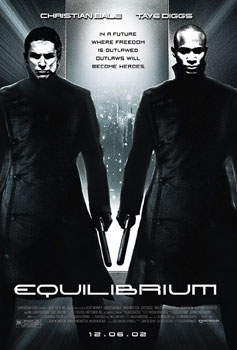

One of my favorite movies is the 2002 science fiction film Equilibrium. Written and directed by Kurt Wimme, the film is set in a future society called Libria. In Libria it is against the law to feel.

One of my favorite movies is the 2002 science fiction film Equilibrium. Written and directed by Kurt Wimme, the film is set in a future society called Libria. In Libria it is against the law to feel.

The main character of the film named John Preston (played by Christian Bale) is a law enforcement officer. He is tasked with destroying objects that could incite emotion, including art, poetry and classical music. He is also required to kill rebels, known as “Sense Offenders”, who choose to experience illegal emotions.

The citizens of Libria have been brainwashed into believing that feelings are the cause of war, suffering and conflict. Accordingly, most of the citizens in Libria willingly participate in their own enslavement by taking a daily injection of a drug, known as Prozium II, which suppresses all emotion.

One day, when Preston accidently misses his dose of Prozium II, he begins to be awakened to beauty through works of art he was hired to destroy. Gradually he begins questioning the disordered sense of morality that had previously motivated his actions. By using his skills in martial arts, Preston eventually is able to overthrow the leadership of the police state and assist the rebels in restoring human emotion to society.

In many respects, the dystopian society represented in Equilibrium is much like our own. This might seem like a strange observation since we live in a time that has elevated emotion to the point of idolatry. Under the guise of “being true to yourself,” often we treat our feelings as self-authenticating. This has even infected the church, where all too often people are ready to assume that if something feels right, then that must be proof of the Holy Spirit’s leading.

Still, there is another sense in which we have become like the citizens in Equilibrium who look on feelings as the enemy, an apt example of the spiritual principle that we destroy whatever we worship idolatrously. Instead of learning to manage, control and talk about our emotions, it is easier to simply eradicate them, drowning out our feelings with noise, addictions, distractions and entertainment. As the great Christian mystic Thomas Merton (1915–1968) observed, our continual saturation in noise keeps modern man alienated from his inner self. If we do not take time to slow down and experience inner stillness, then often we do not even know what we are feeling and we run the risk of becoming strangers to ourselves. Gender stereotypes have also contributed to widespread emotion-suppression, as countless men feel they cannot share what they are feeling for fear of appearing “sissy.” Similarly, many women fear being rejected if they open up and become vulnerable about their emotional struggles. Even our closest relationships often do not provide the safety to share what is really going on inside of us, and so our calls for emotional connection become distorted by fear, frustration and misunderstanding.

It is easy to react to the subjectivism of our culture by becoming like the citizens in Equilibrium and embracing a rationalism that denies both the role of feelings and the important role that beauty plays within the moral ordering of our lives. This is a mistake because it is through an emotional attraction to beauty that we are motivated to make moral judgments and to order our lives according to transcendent realities. Through the sense of beauty we are moved out of indifference to become emotionally invested in pursuing one outcome rather than another. For example, when Eve succumbed to the temptation to disobey God (Gen. 3:6), it was because the beauty of the tree and its effects (“pleasant to the eyes… desirable to make one wise”) captured her imagination with greater force than the beauty of remaining faithful to the will of God. That example might lead us to disparage the role of beauty in moral decision-making, and yet the same principle also works in the other direction as the Holy Spirit sanctifies our feelings and imagination. Through a sense of Christ’s beauty, we become emotionally invested in following Him. For example, when we observe character traits in Bible characters and saints that are worthy of emulation, when we identify certain conditions as honorable or shameful, when our praise of God is rooted in heart-felt admiration, or when we order our actions based on a longing for outcomes that lie outside the scope of the present life but which are attractive to our imagination—when we experience these types of emotions it is because of “the beauty of holiness.” (Ps. 96:9) A rightly-ordered sense of beauty is thus central to the moral imagination of the believer.

Tune-in To Your Feelings

In 2016, I was hired to write curriculum for five different universities to use in their graduate programs. The topic I was asked to research was about integrating mindfulness practices into the classroom and using mindful breathing to help students and teachers develop emotional intelligence. These universities wanted to use my curriculum for the continuing education of teachers who were enrolled in their graduate programs.

Part of my studies on mindfulness involved spending months reviewing the research on emotional intelligence. I came away from these studies convinced that a person’s wellbeing, overall success in life and the quality of their social interactions, are all largely determined by the level of emotional intelligence.

Emotional intelligence is the term psychologists use to refer to a person’s ability accurately to perceive emotions in himself and others, and to use this information to act wisely.

An emotionally intelligent person is able to correctly identify how she is feeling and to self-regulate her internal states, as opposed to simply being carried away by her latest emotion. Someone with emotional intelligence is also able to perceive and understand what other people are feeling even when the other person’s feelings may be very different to her own.

For centuries, Christian theologians and mystics have understood the importance of emotional intelligence. For example, Psalm 42 demonstrates a high level of emotional intelligence, as the Psalmist is able to correctly identify how he is feeling and then use that knowledge to make wise decisions, including the decision to turn to God for help. (We’ll look more closely at Psalm 42 at the end of this section.)

One of the reasons so many people find it difficult to accurately identify their emotions is because their default response is to judge their feelings, labeling them as either “good” or “bad.” An alternative approach is not to judge our emotions but to see them as messengers offering valuable insight into ourselves, our circumstances and our relationships. For example, Alice feels anxiety every time Eric raises his voice at one of their children. This anxiety has the potential to shed light on some unresolved tension in the family, going back to the time when Eric was harsh with one of the children. This unresolved tension may need to be faced and worked through. The anxiety Alive feels when Eric raises his voice needs to be taken seriously and listened to. However, if Alice judges her feelings of anxiety instead of listening to them, then this valuable insight may be lost.

The point is that emotions are important messengers that may be trying to tell us something, and by developing emotional intelligence we can learn to listen to them. That does not mean that there is no such thing as disordered emotions. But even disordered emotions (i.e., self-pity, avarice, hopelessness, envy, lust, etc.) have the potential to tell us something valuable, perhaps even something uncomfortable that we need to face about ourselves. As we grow in emotional intelligence, we can begin befriending even disordered emotions and learning to listen to them.

“Our thoughts, moods and desires set a path for our life”, Elder Thaddeus once observed. He continued:

If our thoughts are quiet, peaceful, and full of love, kindness, and purity, then we have peace, for peaceful thoughts make possible the existence of inner peace, which radiates from us. However, if we breed negative thoughts, then our inner peace is shattered…. Look at us: as soon as our mood changes, we no longer speak kindly to our fellow men, but instead we answer them sharply. We only make things worse by doing this. When we are dissatisfied the whole atmosphere between us becomes sour, and we start to offend one another.

The type of emotional self-monitoring that Elder Thaddeus advocated is crucial if we are to achieve the type of self-rule that the Bible impresses upon us (Prov. 25:28). By pausing in the stream of life to be attentive to our moods and feelings, we can take a deep breath and ask questions like the following:

- When did I begin feeling like this and why?

- When I feel anger, frustration or judgment, are these simply symptoms of prior underlying emotions?

- When did my mood change to become darker? Was it because of unhealthy thoughts?

- Have I taken something personally that I ought to let go?

- When I get angry, what is behind that? Is it really entirely the other person’s problem, or is his/her problem getting blurred with my own issues?

- Am I feeling this way because I am acting as if I am all alone, independent of God?

- Does my lack of peace arise from any thinking errors, such as comparing myself to others or inappropriate self-criticism?

- Is the reason I’m stressed right now because I am trying to control a situation I’ve already handed over to God?

- Is the reason I get easily annoyed by a certain person because I am harboring unresolved hurt? If so, am I open to allowing God to bring this hurt to the surface so I can deal with it?

- Are the emotions I’m feeling right now because of a rigid insistence on my need to be right, or a refusal to view things from someone else’s perspective?

The goal in asking these types of questions is to bring self-awareness to our feelings instead of merely being carried away by them. Often we simply feel one thing then another, then another, without always realizing where these feelings are coming from, and without understanding why we react like we do. Consequently, we have a hard time identifying and managing our emotions. Emotional self-knowledge is a way to move into the realm of self-mastery. By getting in touch with our feelings, we can begin to increase the distance between stimulus and response and thus to cooperate with divine grace in the soul’s purification. By beginning to develop emotional intelligence, we can start managing and working through what we are feeling.

One way of working through troubled emotions is to let them come to the surface and breathe a little, like the complaints issued by the Psalmist in Psalm 41 and 42. It’s easy to feel ashamed of our emotions and retreat behind a stoicism that says, “I’m not lonely,” “I’m not scared,” “no one can ever hurt me”, “I will never let myself become vulnerable again.” In such a hardened state, we may find it hard to be real with God about our needs, struggles and temptations. Even though God knows us better than we know ourselves, we often still feel embarrassed coming to Him and being totally honest with the pain we’re feeling.

One of the reasons that Psalm 42 is my all-time favorite chapter of the Bible is because it continually zigzags back and forth between a painful transparency of troubled emotions (“My tears have been my food day and night…why have You forgotten me?”) and a child-like trust in God. I believe there is an important connection between these two aspects: the act of being vulnerable with God about our darker feelings enables us to receive the comfort and healing He longs to provide. Let’s look closer at Psalm 42. Notice how the emotional self-monitoring (“I pour out my soul within me…my soul is cast down”) is integrally connected to wise self-talk (“Why are you cast down, O my soul?”) and appropriate decision-making (“Hope in God, for I shall yet praise Him”). I encourage you to slowly read all of Psalm 42 with this in mind.

As the deer pants for the water brooks,

So pants my soul for You, O God.

My soul thirsts for God, for the living God.

When shall I come and appear before God?My tears have been my food day and night,

While they continually say to me,

“Where is your God?”When I remember these things,

I pour out my soul within me.

For I used to go with the multitude;

I went with them to the house of God,

With the voice of joy and praise,

With a multitude that kept a pilgrim feast.Why are you cast down, O my soul?

And why are you disquieted within me?

Hope in God, for I shall yet praise Him

For the help of His countenance.O my God, my soul is cast down within me;

Therefore I will remember You from the land of the Jordan,

And from the heights of Hermon,

From the Hill Mizar.Deep calls unto deep at the noise of Your waterfalls;

All Your waves and billows have gone over me.

The LORD will command His lovingkindness in the daytime,

And in the night His song shall be with me—

A prayer to the God of my life.

I will say to God my Rock,

“Why have You forgotten me?

Why do I go mourning because of the oppression of the enemy?”As with a breaking of my bones,

My enemies reproach me,

While they say to me all day long,

“Where is your God?”Why are you cast down, O my soul?

And why are you disquieted within me?

Hope in God;

For I shall yet praise Him,

The help of my countenance and my God.

Tune Into Your Emotions by Listening to Your Body

We have looked at the importance of listening to our feelings and emotional intelligence. But exactly how does one develop this skill? Is emotional intelligence something a person is simply born with?

A clue to answering this question emerged when a group of scientists at the University of Iowa set up a gambling exercise in which participants had sensors attached to their hands. Each person was then asked to pick cards from a red deck or a blue deck. In the course of the game, the participants eventually all realize that over time it is only possible to win by taking cards from the blue deck. But most people didn’t realize that until turning over 80 cards. However, the significant part of the experiment occurred before each participants consciously realized that the red deck was disadvantaged. About 40 cards into the game, their palms began to sweat when reaching for a card from the red deck—a clear sign of nervousness. But this is rather strange, because it means that their body knew there was something wrong with the red deck 40 cards before their conscious mind was aware of it.

This experiment demonstrated a truth that we’ve all experienced: emotions have physical effects. Moreover, emotions often affect the body before we are even conscious that we are experiencing the emotion. This fact offers a clue to how we can grow in emotional intelligence. By learning to listen to your body, you can learn better to tune-in to your emotions.

This is easier said than done. In our age of constant noise and stimulation, it is easy to be inattention to the signals from our body. Sometimes we fail to read our body’s warning signs and so we simply react to the results of being hungry, having a headache, experiencing stress, having bad posture, being tired, or having an unhealthy heart-rate. Even when these conditions have reached the point of becoming symptomatic, we often merely treat the symptoms instead of listening to what our body is trying to tell us. For example, we deal with being tired by drinking coffee instead of making sure we get enough sleep; we deal with back pain by taking pain medication instead of making long-term corrections to our posture; we deal with stress by escaping into an even more busy life instead of taking time to pursue appropriate self-care activities.

By achieving present-moment awareness of the body, we can start listening to the messages our physical self is trying to send us, including messages about our emotions. By being mindful of our body, we can learn to preserve enough distance between ourselves and incoming stimuli in order to attend to our physical needs and make wise choices as a result. Let’s take a few examples of how this looks in practice.

Suppose a young man’s attention is so absorbed playing computer games that he doesn’t realize how hungry his body has become and that he actually needs to stop for something to eat. Or maybe he doesn’t realize that it’s 2:30 AM and that his body is sending him signals that he needs to go to bed. In such cases, because the young man’s attention has been scattered by the latest mental or emotional stimuli, he is unable to perceive what is happening in his body. Or suppose a girl is so absorbed in a stressful conversation that she doesn’t realize she’s getting a stress-induced headache and needs to pause to take some deep breaths, or maybe that she needs to postpone the conversation for another time after her heart rate is at a healthier rate.

The cash-value of giving this type of attention to your body goes beyond physical self-care and actually helps us better to regulate what is happening in our emotional life. Remember, subtle changes in mood are often experienced first in the body and only afterwards by the conscious mind.

If you’re skeptical of what I’m saying, try a little experiment. The next time you’re feeling stubborn or defensive, notice how it makes your body feel. Do you feel a tightening of the neck muscles? When you’re grieving, how does that effect your body? When you’re angry, anxious or worried, how does that make your body feel? When you feel embarrassment or shame, how does that impact your body?

By learning to “tune-in” to your body like this, you can begin picking up valuable clues about your emotional life. Scientists are discovering that this type of body-awareness is central to growing in emotional intelligence. This is what Chade-Meng Tan discovered while working as an engineer with Google. The company allowed Meng, as he likes to be called, to spend some of his work time researching the connection between body-awareness and emotional intelligence. Meng’s work was so helpful for workers at Google that the company eventually moved him into Human Resources so he could work full time in helping people become more mindful about their body and emotions. In his book Search Inside Yourself, Meng described the importance of tuning into your emotions by listening to your body.

“Every emotion has a correlate in the body. Laura Delizonna, a researcher turned happiness strategist, very nicely defines emotion as ‘a basic physiological state characterized by identifiable autonomic or bodily changes.’ Every emotional experience is not just a psychological experience; it is also a physiological experience.

“We can usually experience emotions more vividly in the body than in the mind. Therefore, when we are trying to perceive an emotion, we usually get more bang for the buck if we bring our attention to the body rather than the mind.

“More importantly, bringing the attention to the body enables a high-resolution perception of emotions. High-resolution perception means your perception becomes so refined across both time and space that you can watch an emotion the moment it is arising, you can perceive its subtle changes as it waxes and wanes, and you can watch it the moment it ceases. This ability is important because the better we can perceive our emotions, the better we can manage them. When we are able to perceive emotions arising and changing in slow motion, we can become so skillful at managing them…”

Learning to tune into our own emotions is only one half of the picture. A Christ-centered emotional intelligence also involves learning to tune into the emotions of others. Let’s look closer at this.

Tune Into Those Around You

Have you ever shared a deeply personal emotion or experience with another person and come away feeling like they just didn’t get it? Did you ever feel that however many different ways you tried to explain yourself the other person, he or she just wasn’t connecting with you? Maybe you came away from the conversation feeling stupid. We’ve all had experiences like that. But most of us have also probably had the experience of sharing something with a person who seemed to immediately “get it” without us even needing to go into a lot of detail. In such a case, maybe the other person seemed to have an intuitive sense of where we were coming from and maybe she could even articulate what you were trying to say better than you could yourself. The simple act of the person listening probably made you feel validated, almost like the person was giving you permission to be you.

The difference between these two scenarios—the one where you felt stupid and the other where you felt validated—often hinges on the level of cognitive and emotional empathy in the person we’re talking with. “Emotional empathy” refers to our ability to feel what another person is feeling even when we have not personally had the same experience. “Cognitive empathy” is similar and refers to a person’s ability to know how the other person feels and what they might be thinking. Both types of empathy enable us imaginatively to extend ourselves into the other person’s frame of reference, which is ultimately an act of love and self-donation. Through empathy it becomes possible for two people who are vastly different to share experiences, to participate in each other’s struggles, sorrows and joys.

Much of the conflict we experience, even amongst people we love, arises because of a lack of cognitive and emotional empathy. When we are not able or willing to tune into other people’s emotions, then unnecessary conflict often arises. Consider that in many relationships between partners or within families, we can be drawn into conflict over trivial matters that should never have become matters of provocation. The reason insignificant things often get blown out of proportion is because they trigger deeper areas of unresolved conflict, hurt, confusion, frustration or insecurity. (See my earlier post about this ‘The Material and Personal Dimensions of Conflict.’) Often the real issue behind a conflict is deeper feelings that have never been properly worked through or even acknowledged. Empathetic listening is a way to acknowledge these deeper issues. If both parties in a conflict are working on becoming more attentive to their own emotions, and if they are also trying to lovingly “tune-in” to what the other person is feeling, then they can take a step back and recognize the emotional dynamics at work. Instead of adopting postures of defensiveness and criticism, they can listen with empathy to what the real issues actually are.

I am becoming increasingly convinced that in our age of distractions, inattention and scattered focus, the greatest gift we can offer someone is simply to listen. When we really make ourselves present to another by truly listening, this is healing. Yet we easily underestimate just how valuable a gift we offer when we simply listen to another person. Conversely, we often fail to appreciate just how much we damage relationships through refusal to listen. This has been proved by Dr. John Gottman, famous for being able to observe a 15 minute conversation between a couple and then predict if their marriage will end in divorce within ten years. Gottman conducted extensive studies aimed at identifying the common causes of marital breakdown. He found that one of “the four horsemen” that almost certainly destroys any marriage is stonewalling—refusal to talk and refusal to listen. For any relationship to work, both parties need to know they will be heard. Many divorces could have been prevented if the parties had only been willing to slow down and work at listening, really listening, to what their partner is trying to say. (In case you’re wondering what the other three marriage-killers are, they are criticism, contempt and defensiveness.)

Further Reading

“Every emotion has a correlate in the body. Laura Delizonna, a researcher turned happiness strategist, very nicely defines emotion as ‘a basic physiological state characterized by identifiable autonomic or bodily changes.’ Every emotional experience is not just a psychological experience; it is also a physiological experience.

“Every emotion has a correlate in the body. Laura Delizonna, a researcher turned happiness strategist, very nicely defines emotion as ‘a basic physiological state characterized by identifiable autonomic or bodily changes.’ Every emotional experience is not just a psychological experience; it is also a physiological experience.