“As the world must be redeemed in a few men to begin with, so the soul is redeemed in a few of its thoughts, and works, and ways to begin with: it takes a long time to finish the new creation of this redemption.”—George MacDonald[i]

“It has been well said that no man ever sank under the burden of the day. It is, when tomorrow’s burden is added to the burden of today, that the weight is more than a man can bear. Never load yourselves so, my friends. If you find yourselves so loaded, at least remember this: it is your own doing, not God’s. He begs you to leave the future to Him, and mind the present.” —George MacDonald[ii]

In Rod Dreher’s book, How Dante Can Save Your Life, he tells the story of his return to Starhill Louisiana, the community where he grew up.

Rod expected to happily reintegrate with his family, but instead he found a web of troubled relationships, misunderstandings, and family secrets. The stress of the family problems became so great that Rod descended into anxiety, depression, and fatigue. With his immune system compromised by the stress, he contracted a debilitating—and potentially life-threatening—virus. Rod’s rheumatologist urged him to flee from the stress by relocating again. This advice seemed to make sense given that his disease went into remission during the times when he was away from the Starhill community. However, instead of packing his bags and leaving, Rod decided to follow his wife’s promptings and see a therapist.

Rod recounts his first session with a man named Mike Holmes, a Southern Baptist preacher who was also a professional counselor. After hearing about Rod’s story, Mike said that instead of trying to fix the situation, he would help Rod view circumstances in a different light.

“…I’m not going to tell you how to fix it,” he said. “But what I am going to do is this. We are going to explore all these stories you’ve told me, and look at them to see where you might be misreading the situation, and where there might be room for positive change.”

“Here’s what I want you to focus on, … You cannot control other people, but you can control your reactions to them.”[iii]

By the end of the book, all the same problems and misunderstandings still persisted in the Louisiana community. But Rod was able to achieve recovery through learning to perceive the situation in a new light, to move out of a narrative in which he was a passive victim. As Dreher quoted his therapist saying towards the end of the book, “You have power over the images you want to let into your mind. You control them; they don’t control you.”[iv]

I’m sure we can all relate to Rod’s struggle. Often when we think we are simply making an objective observation about a situation, we are actually reacting to the situation as viewed through the lens of a script our minds have created to explain the situation.

Research shows that much of what we experience in life is fundamentally ambiguous and open to a variety of interpretations.[v] One of the ways we make sense of life’s circumstances is by the meanings we ascribe to what we encounter. The narratives we tell ourselves have enormous power because of the web of reciprocities linking how we think with how we feel, behave, and relate to others. The problem arises when we impose meanings onto our experiences that stem from distorted or incomplete views of reality. Sometimes the narratives we tell ourselves are rooted in defense mechanisms that keep us tethered to self-deception, self-justification, victimhood, or enabling behaviors.

Thoughts, Feelings and Behavior in Historical Perspectives

Ancient wisdom has emphasized that disordered feelings often arise because of prior problems in thinking and behavior. For example, the first-century Stoic philosopher, Epictetus, taught that our interpretations of events have a greater impact on us than the events themselves. “Men are disturbed, not by things,” Epictetus commented, “but by the principles and notions which they form concerning things.”[vi] Accordingly, Epictetus taught that the way to avoid unnecessary suffering is to engage in correct thinking. A similar idea can be found in the desert fathers of the Christian tradition, who often taught that the way to address problems in one’s emotional life is first to attend to what is happening in the realm of thinking and behavior.

Despite this ancient teaching, throughout much of the modern history of psychology, very little attention was given to the notion of changing maladaptive feelings through addressing thoughts and behavior. As I wrote in my Salvo article “Remembering Aaron Beck (1921–2021)”

“Under the influence of Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) and his successors, much late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century psychologists saw feelings as uncontrollable impulses from a dark unconscious, the result of processes over which we have little control.

The mid-twentieth century, with its fetish with mechanization and materialism, saw a swing of the pendulum away from Freud. Behaviorist theories pioneered by men like B.F. Skinner (1904-1990) began emphasizing only what is measurable and observable. Behaviorism was part of a movement to buttress psychology’s standing as a science, not a discipline based on speculative theories about consciousness. While behaviorism yielded significant insights about the ways that human beings and animals learn and develop habits, it adopted a simplistic approach to feelings and thoughts, as if these are merely responses to controlling variables rather than aspects that can be controlled through personal agency (behaviorists like John B. Watson and B.F. Skinner actually rejected free will).”

In the latter half of the twentieth-century, researchers working within the framework of Cognitive Therapy made huge strides for better understanding the interconnectedness of behavior, feelings, and thoughts. Psychologists began to recover the ancient understanding that before effective behavioral modification can occur, there needs to be internal changes of attitude and thoughts, not simply altered variables in one’s external environment. For example, Aaron T. Beck famously identified different ways that our thinking distorts reality, contributing to disorders like anxiety and depression.

Despite these advances in psychology, on a popular level many people still perceive their feelings as having a life of their own outside their own control. For example, many people make a false dichotomy between feelings and skills, assuming that feelings simply happen, without sufficient awareness given to the way our emotions can be skillfully managed. But since the human will, mind, emotions, and spirit influence each other in complex webs of reciprocities, the way to work long-term transformation in one’s emotional life is often first to bring thoughts and behavior and spiritual practices into a healthier condition. For example, when problems in our emotional lives start to appear insurmountable, it can be helpful to stop and take a thought-life inventory, asking ourselves questions such as the following:

- What am I spending my time thinking about?

- How might my thought-life be feeding unhealthy emotional reactions?

- What kind of negative self-statements am I believing about myself throughout the day?

- Am I dwelling on everything that is wrong in my life, or ruminating about the future, or entertaining thoughts that lead to self-pity?

- Am I believing disordered or incomplete narratives about others in my life?

Careful answers to these questions may reveal some surprising insights into how your thought-life relates to your emotional well-being. You may also begin to notice times when your emotions become disturbed by various thinking errors. In the rest of this article, we will identify a few common thinking errors, beginning with negative automatic thoughts. These thinking errors are important to understand since it is during periods of our life when we are suffering that we can be the most susceptible to them.

Negative Automatic Thoughts

When Renee was a child, her family moved around a lot for her father’s work. Every few years Renee found herself in a new community, a new school, and a new set of friends that she had to get to know from scratch. Renee found it hard to form relationships since she always expected to be uprooted again. Not surprisingly, Renee had become very shy and suffered from mild forms social anxiety.

When Renee was seventeen, her family finally settled in a small town in Colorado. Having been assured by her parents that they would not be moving again, Renee desperately wanted to make friends in the new community. She especially wanted to have a boyfriend. But at the same time, Renee was scared of forming relationships.

The second Sunday in their new church, the youth pastor spotted Renee and invited her to their Friday youth group. Renee’s mother encouraged her to attend as an opportunity to meet some of the other young people in the area.

When Friday evening arrived, the youth group was not what Renee had expected. After everyone sang and listened to a short talk from the youth pastor, the rest of the evening was unstructured. Everyone grouped together with their friends, leaving Renee to sit quietly in a corner feeling more and more awkward. She began to get frustrated and even a little angry.

Renee didn’t know why she was feeling angry, but unconsciously she was thinking something like this: nobody likes me, I’ve never been able to fit in, and no young man will ever want to have me as his girlfriend. Renee was not consciously thinking any of these things—it was more of an impression, leading to a growing sense of frustration.

After about fifteen minutes, a young man with bright red hair came up to Renee and introduced himself. He was a friendly boy who seemed to sense that Renee was uncomfortable. “You’re new here, right?” he said.

“Yes,” Renee replied cautiously. “We just moved to the area.”

“I’m Joe,” he said, holding out his hand. “Well, come on, I’ll introduce you to some of the gang.”

When Renee got home that night, she cried and cried. She just knew she would never to fit in anywhere!

Renee’s mother, Lisa, was a caring woman who desperately wanted the best for her daughter. But Lisa had trouble understanding Renee, who was so different from herself. Lisa was an outgoing bubbly woman and found it hard to relate to her daughter’s complex emotions and social anxiety.

One of Lisa’s best friends, Olivia, had been planning to come and visit that weekend. Since Olivia had just qualified to be an LPC (licensed professional counselor), Lisa asked Oliva if she could talk to her daughter. Renee had known Olivia since a child and always felt comfortable around her. Even though they weren’t related, Renee had grown up referring to her mother’s best friend as “Aunt Olivia.”

The next day, over a cup of coffee, Renee told Aunt Olivia about the incident at the youth group. Olivia was naturally inquisitive and began probing her in order better to understand what had happened. At first, Renee couldn’t explain why she felt so miserable on the evening of the youth group. However, as Olivia helped Renee reconstruct her experiences, it gradually became clear that her sense of frustration and isolation had partly been the result of automatic thoughts. Renee remembered that she had been thinking things like, “Nobody likes me,” “I’m never going to fit in,” or “Joe is just being friendly because he feels sorry for me” and “I’m unlovable.” These thoughts had caused an emotional tidal wave for Renee that left her feeling frustrated, helpless, and isolated.

“Automatic thoughts are impressions or images that flash through our mind with or without us consciously choosing,” Olivia explained. “They are usually triggered by events, or our interpretation of events, and then lead to various emotional—and sometimes even physical—symptoms.”

“I think that happens to me a lot,” Renee put in. “But what can you do about it?”

“Well, when I’m experiencing negative automatic thoughts, I find it helpful to first be aware of what the automatic thoughts actually are, and then to perform a reality check on them.”

“A reality check?” asked Renee. “What’s that?”

“A reality check simply involves asking ourselves if we have an objective basis for believing the automatic thoughts that are passing through our brains. In your own case, that might involve considering whether anything happened the other night to actually substantiate the thought that you will never fit in or that you are unlovable. From what you told me, it sounds like you actually have the potential to fit in very well because there are a lot of friendly people in your new church who want to include you in their activities. You actually have a basis to be encouraged. That is the truth of the situation, not the lies that your automatic thoughts were telling you.”

Then, moving slightly closer to Renee as if to let her into a little secret, Olivia explained, “You know, this sort of thing happens to me all the time. I am constantly plagued by untrue automatic thoughts. For example, on the morning when I was scheduled to take the National Counselor Examination, I began to break out in a sweat and have dry mouth. I didn’t understand why I was having these symptoms because I didn’t think I was particularly nervous. But then I realized that all morning I had been having the automatic thoughts, such as that if I fail this will simply prove I’m stupid, or that I’m a fake and have no business trying to be a professional counsellor, and so on. At other times I have automatic thoughts like ‘I’m unable to cope’ or ‘Something bad is probably just about to happen.’”

Renee was surprised to learn that Aunt Olivia also struggled with negative automatic thoughts. She had always thought of Aunt Olivia as confident and self-assured. Renee reflected a bit before bringing the conversation back to the events at the youth group.

“I wasn’t consciously thinking any of those things when I was at the youth group,” Renee responded. “In fact, I didn’t even understand why I felt like I did until a few minutes ago when you started asking me about it.”

“That’s exactly the point about automatic thoughts,” Olivia put in. “They are not like the types of thoughts we consciously choose. Automatic thoughts are like a non-stop radio playing in the background rather than an actual song that you pull up on your phone and choose to play. Does that make sense?”

“Yes, it makes a lot of sense,” Renee replied reflectively. “I think I’m am troubled by automatic thoughts a lot of the time. But what can I do about it, especially if I don’t even realize until afterwards that it’s even happening?”

“Well, in my own case,” Olivia shared, “I find that training myself to become aware of my automatic thoughts is half the battle. I’m like you in that I often don’t even realize the automatic thoughts that are going through my mind and afflicting me. But once I’ve identified the problem, then I can do a reality-check by asking, ‘Is there any reason that I should be listening to these automatic thoughts?’ I also ask myself questions like, ‘How are these automatic thoughts making me feel?’ Generally, if a thought disturbs your inner peace, then it isn’t from the Lord. Ultimately, it’s a matter of asking the Holy Spirit’s help to take every thought captive to the obedience of Christ, like Paul talked about in 2nd Corinthians 10. It’s not a battle you can fight on your own, but something you need to constantly look to the Holy Spirit to help you with.”

Renee’s story introduces the first of the six thinking errors we will be exploring in the rest of this article.

We have all read verses in the Bible like Phil 4:8 and Col. 3:1-2, so we know that God wants us to have a positive Christ-centered outlook on life. So why do we find it so difficult? Why do we allow little things to get us down? Why do we obsess over the future and ruminate over the past without simply basking in the blessing of the present? Part of the answer has to do with automatic thoughts.

Automatic thoughts are not necessarily bad and are part of how we survive in the world without having to deliberately calculate every situation that comes along. The role that automatic thoughts play in survival may have their origin in our distant hunter-gatherer past. The survival of our hunter-gatherer ancestors depended on “problem fixation,” which means giving constant attention to anything in the environment that might be threatening, lacking, or problematic. By identifying a potential problem, the body is able to respond with increased cortisol, the stress hormone that enables us to quickly react to danger. For example, if you were on a hunt and saw signs of a snake down the path, your survival would depend on being able to quickly recognize the signs and act accordingly. If you had a bad experience with a neighboring tribe in a certain area, your brain would need to remember the place of danger so that when you find yourself there again you could prepare to fight, flee, or freeze. In short, during our hunter-gatherer past we needed to remember everything that went wrong, to analyze our environment for potential problems, to constantly scan our experience for things that are abnormal or lacking. Moreover, we always needed to be thinking two or three steps ahead so as not to become vulnerable to a predator. The human brain is very efficient, and so this type of problem-fixation often occurs in the background of our brain independently of our conscious control, like the operating system on a computer.

You and I no longer live in a world hedged about by constant danger, and those dangers that do exist cannot injure us spiritually without our consent. However, even when our lives are safe, our brains easily default to our primordial condition of scanning our experience for problems. The habits of analyzing, ruminating, worrying, planning, remembering, analyzing, evaluating and problem-fixation have become so second-nature to us as a species that these types of thoughts often occur automatically.

Most automatic thoughts flow out of our mind as quickly as they come, leaving a residue on our unconscious. Every day we have thousands of thoughts, and if even 15% of these thoughts are negative then that amounts to hundreds of negative thoughts in a single day. Over a lifetime, this accumulative load of negative thoughts can begin to have an impact on our self-identity, our view of the world, and our health. (Symptoms associated with stressful thoughts include heart disease, stroke, decreased immune function, and cognitive decline.[vii])

To start observing all your automatic thoughts would be paralyzing, just as it would be impossible to get work done on a computer if you are constantly watching what is happening in the background with the operating system. However, just as a computer’s operating system might get infected with a virus and require special attention, so our automatic thoughts sometimes require special attention when they become toxic.

How do you know if your automatic thoughts are toxic? There is no one-size-fits-all answer to this question, but a good rule of thumb is this: if a thought causes you to lose your peace, or if you find yourself becoming more and more frustrated, angry, agitated, stressed, or proud, then it might be time to give attention to your automatic thought and perform a reality check on them.

Another way to assess whether our automatic thoughts are healthy or toxic is to ask if they are problem-solving or problem-forming. Here are some examples of automatic thoughts that are problem-forming instead of problem-solving.

- Negative views about the self. Negative views of the self often arise from a self-schema (a mental model of the self) rooted in negative early experiences. If we had parents who criticized or abandoned us, if we were exposed to bullying at school, or if we had other significant challenges during childhood, then this can wire the brain for automatic thoughts that come to us in the form of negative reflexive self-statements. Common negative self-statements include things like,

- “I’m unlovable”

- “it would be better if I were more like so-and-so”

- “I can’t learn new things”

- “I’m ugly”

- “my personality stops me from being able to do such-and-such”

- “I’m worthless”

- “I don’t deserve to be happy, so I’ll block myself from enjoying this”

- Negative views about others. Some automatic thoughts come in the form of judgement and criticism against other people. The problem with these types of automatic thoughts is that they give other people power over us. The more you focus on the wrong other people have done to you, the more you are opening a space in yourself where those wrongs can reverberate and destroy your peace.

- Negative views about the world and social environment. If we were exposed to danger in early childhood, or if we have unresolved trauma, this can lead to negative automatic thoughts about the world around us. The world begins to be perceived as a threatening place and we may look upon others—perhaps even people who love us—with suspicion. This can lead to negative automatic thoughts about our social environment such as,

- “everyone is probably judging me right now”

- “no one values my opinion”

- “everyone is out to get me”

- “people probably think I’m stupid”

- “nobody likes me”

- “I will always be overlooked”

- ‘they are probably thinking about how overweight I am”

- Negative views about the future. Automatic thoughts about the future lead to a constant sense of foreboding, and a sense of dread as if danger is waiting just around the corner. Some common negative automatic thoughts about the future include things like,

- “I’m probably going to lose my job”

- “things can only get worse from here”

- “I’ll never be able to learn what I need to know”

- “when I get older, I’ll probably be just like my parents when they were old”

- “things have been going so well for me that this probably won’t continue”

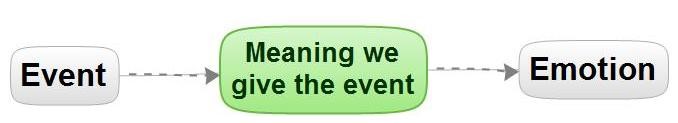

These types of negative thoughts about the self, our environment, and the future do not necessarily correlate to what is actually happening in a person’s life. If someone is weighed down by negative automatic thoughts, they tend to be tormented even when things are going comparatively well. Similarly, if someone’s mind is filled with positive thoughts like appreciation, compassion, and contentment, then they tend to have peace of mind even when things are going wrong in their life. The difference largely comes down to the meanings we ascribe to our life. This can be illustrated by the following diagram.

To understand this three-fold progression, think back to the example I gave earlier about the hunter-gatherer. The event of observing unusual markings on a path is not inherently frightening or stressful in itself; rather, it is what the unusual markings mean (e.g., the potential presence of a snake or enemy) that elicits the particular emotional reaction. What often occurs, however, is that our negative automatic thoughts impose false meanings on the events we experience, as Renee did when she began imagining that Joe was only being friendly because he felt sorry for her. When we impose false meanings onto events, the result is disordered emotional reactions. Once we are aware of these meanings, then we can shed the spotlight on automatic thoughts that might otherwise go undetected. Once we recognize that our automatic thoughts are imposing negative meanings onto our experiences, then we can begin asking ourselves if we want to believe those meanings. It can be helpful to remind ourselves that negative automatic thoughts need not have power over us until we choose to believe them.

Many of the early Church Fathers spoke about mindful vigilance as a way of combatting harmful thoughts. Here’s how Fr. George Morelli explained the ancient Christian teaching about guarding the mind.

“The early fathers of the Eastern Christian Church talked about the vigilance of the mind and heart [nepsis], which is similar to the cognitive-rational-emotive therapy technique employed by psychologists in helping patients to be ‘mindful’ and thus learn to control their thoughts and feelings…. Once we detect a habit that we have that is harmful, or an emotional reaction we have that is damaging to ourselves or others, we can choose to place ourselves “at the head of the column,” to be mindful, watchful, vigilant and to prepare a counteraction: an alternative competing response, a different interpretation of the events around us and a different feeling about the whole incident. This is would be applying the technique of Christian mindfulness.”[viii]

Negative Filtering

Filtering is the thinking error that occurs when we look at an entire situation and hone in on specific negatives while overlooking positives that might balance things out.

How many times do we think about our day, our job, our friendships, or our family relationships in a way that filters out what is good while giving inordinate attention to what is bad? It can be easy for negative details to become so magnified in our thinking that we filter out more positive aspects that could bring things into a healthier perspective. Filtering often happens in married relationships, where a wife will become so accustomed to her husband’s good qualities that she will begin overlooking those qualities and focusing instead on his imperfections. (And, of course, husbands make this same mistake too.)

Filtering can also occur n the other direction, when a person filters out negative aspects of a situation, ignoring problems that actually need to be addressed.

The English Puritan teacher, Richard Baxter (1615–1691), had occasion to counsel many a husband who was filtering out the goo qualities of his wife, giving unbalanced attention to what was negative.[ix] In Baxter’s “sub-directions for maintaining conjugal love,” he wrote to husbands, urging them to filter in a positive direction instead of a negative one. His words are worth quoting in full. Although Baxter is specifically talking about marriage, the same principles apply in a variety of contexts and relationships.

“Take more notice of the good, that is in your wives, than of the evil. Let not the observation of their faults make you forget or overlook their virtues. Love is kindled by the sight of love or goodness.

Make not infirmities to seem odious faults, but excuse them as far as lawfully you may, by considering the frailty of the sex, and of their tempers, and considering also your own infirmities, and how much your wives must bear with you.

Stir up that most in them into exercise which is best, and stir not up that which is evil; and then the good will most appear, and the evil will be as buried, and you will more easily maintain your love. There is some uncleanness in the best on earth; and if you will be daily stirring in the filth, no wonder if you have the annoyance; and for that you may thank yourselves: draw out the fragrancy of that which is good and delectable in them, and do not by your own imprudence or peevishness stir up the worst, and then you shall find that even your faulty wives will appear more amiable to you.

Overcome them with love; and then whatever they are in themselves, they will be loving to you, and consequently lovely. Love will cause love, as fire kindleth fire. A good husband is the best means to make a good and loving wife. Make them not froward [ornery or contrary] by your froward carriage, and then say, we cannot love them.

Give them examples of amiableness in yourselves; set them the pattern of a prudent, lowly, loving, meek, self-denying, patient, harmless, holy, heavenly life. Try this a while, and see whether it will not shame them from their faults, and make them walk more amiably themselves.”[x]

Emotional Reasoning

The thinking error of emotional reasoning occurs whenever we allow our feelings to lead our thinking into error, or when we treat our emotional reactions as if they are self-authenticating.

Elsewhere I have discussed the importance of tuning into our emotions and listening to our feelings. But that type of emotional self-awareness is not the same thing as treating our emotions as self-authenticating. It may seem obvious, but it is still worth pointing out that just because something feels true does not mean that it actually is. Often we need to first check to see if our feelings are rooted in fact. This is similar to how Olivia helped Rene perform a “reality check” on how she was feeling after the incident at the church youth group.

Here are some examples of emotional reasoning:

- “I feel shame; therefore I must be a horrible person.”

- “if feel scared about moving, and therefore I shouldn’t do it.”

- “I know my spouse is cheating on me, because otherwise why would I feel jealous?”

- “I feel unlovable; therefore I know that nobody will ever accept me.”

- “what he did made me feel hurt; therefore, he must be in the wrong.”

- “because I skipped my exercise yesterday, I feel like I will never be able to follow through on anything.”

- “I feel like I can’t cope with this; therefore, I can’t cope with it.”

God has given each of us a precious gift for dealing with these types of emotional challenges, and that gift is our prefrontal cortex. This is the part of the brain that enables you to observe your own thinking. Animals can’t do that. Animals can think, but they can’t think about thinking; they can’t observe what is happening in their brains. But human beings can think about thinking, thanks to the prefrontal cortex. Your prefrontal cortex is like your brain’s guard house, tasked with controlling what enters. As thoughts arise in your brain, you can use your prefrontal cortex to watch what is happening and exercise second-by-second censorship, weeding out toxic cognitions and thinking errors.

Often emotional reasoning hijacks ourprefrontal cortex and distorts our thinking without us even realizing it. I was reminded of this in October 2018 after my father asked me to speak at a literary conference he was sponsoring on the works of George MacDonald. One gentleman at the conference, a counselor named Tom Petit, took me out to lunch so we could discuss the intricacies of the human brain. In the course of our fascinating conversation, I shared with Tom that I struggle to remain resilient in the face of stress. In neurological terms, I shared that my amygdala (the instinctive part of the brain that signals the alarm for danger) often hijacks my executive functions (the part of the brain involved in wise decision-making), leading to fight-flight-freeze responses. Tom listened patiently and then asked a very penetrating question that has changed how I approach stressful situations.

“When something happens that triggers an intense emotional reaction for you—whether a reaction of danger, shame, anxiety, sadness, or some other feeling—what does it feel like it means?”

I slowly repeated Tom’s simple but profound question to myself. “What does it feel like it means?”

“You see, Robin,” Tom continued, “when we experience difficulties, the emotional part of our brain tends to take a snapshot of the worst aspects of the situation. This happens for the sake of our safety in order to give us a strong incentive to avoid a repeat of a potentially dangerous situation. But the problem is that the emotional brain isn’t very good at remembering the good side of situations.”

“Can you give me an example?” I asked.

“Well,” Tom said, “when we go through challenging situations, our emotional brain easily forgets things like, ‘God was with me in the midst of this trial,’ or ‘all things considered, I actually coped with this pretty well,’ or ‘The Holy Spirit helped me to grow through this painful experience,’ or ‘if this happens again, I will know how to handle it better.’ Instead of remembering these aspects of the situation, the emotional brain tends to latch onto the worst part of the experience and just remembers that. Moreover, as part of our harm-avoidance system, the emotional brain tends to remember only the perceived meaning of an event and not the actual meaning. Stopping to ask, ‘what does this feel like it means?’ or ‘how am I emotionally interpreting this experience?’, is a way to help uncover these perceived meanings and then examine them in the light of reality.”

“What would be an example of what you’re calling a ‘perceived meaning’?” I asked.

“Well, often the perceived meaning of a traumatic event is something like, ‘it feels like I have to keep living through what happens,’ or ‘it feels like God could never love me after this,’ or ‘I’ll never be able to move on after this,’ and so forth. These perceived meanings can be very powerful in defining our experiences for us.

“When we feel these things,” Tom continued, “it can be helpful to pause and ask, ‘What is it that I really want? In the midst of that painful experience, what is it that I would love to have had access to?’ For most people, what they want to have access to is the truth. For example, if my emotional brain sends the message ‘I’m going to be left all alone,’ then the truth I want access to is that I will never be left alone. If the emotional brain sends me the message, ‘I am stupid and worthless,’ the truth I would love to access is that I am worthy and valuable. If the emotional brains sends me the message ‘I will never see my friend again,’ then the truth I want access to is that we will be reunited in Christ.”

“Once we begin putting it in these terms,” Tom concluded, “we can see that we already have access to the truth we want. By learning to connect with the truth, we can gradually begin replacing the perceived meaning of our past with a new meaning. As George MacDonald said, ‘there is no veil like light —no adamantine armour against hurt like the truth.’”[xi]

From there, Tom went on to share various Scriptures he uses to move from the perceived meaning of an event to the actual meaning. When our lunch was over, I took out a piece of paper and made the following diagram of what Tom had shared.

|

Perceived Meaning of Troubling Event (“what does this feel like it means?”) |

What I Would Like to Have Had Access to in the Midst of Troubling Event |

Actual Meaning I Can Have Access To

|

|

| This feels like it means I’m not lovable. | I would like to have access to unconditional love. | “For I am persuaded that neither death nor life, nor angels nor principalities nor powers, nor things present nor things to come, nor height nor depth, nor any other created thing, shall be able to separate us from the love of God which is in Christ Jesus our Lord.” (Rom. 8:38-39)

|

|

| This feels like it means that God can never love me again.

|

I would like to have access to forgiveness and cleansing.

|

“If we confess our sins, He is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness.” (1 Jn. 1:9)

|

|

| This feels like it means I’m weird and abnormal.

|

I would like to have access to the knowledge that I am worthy and valuable.

|

“I am fearfully and wonderfully made.” (Ps. 139:14)

|

|

| This feels like it means I’m going to be left all alone.

|

I would like to have access to the knowledge that I will never be left alone. | “For He Himself has said, ‘I will never leave you nor forsake you.’” (Heb. 13:5)

|

|

| This feels like it means I’m unworthy and not good enough.

|

I would like to have access to the knowledge that I am fully accepted. | “…to the praise of the glory of His grace, by which He made us accepted in the Beloved.” (Eph. 1:6)

|

|

| This feels like it means my loved one is lost forever. | I would like to have access to the knowledge that I will see my loved one again.

|

“Then we who are alive and remain shall be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air. And thus we shall always be with the Lord.” (1 Thess. 4:17)

|

|

Comparison

“He and I went to school together,” Douglas shared with me, “and we both started out with the same opportunities. But thirty years later, his life has been successful and mine has not. Oh, if only I had made different choices when I was younger—then I might have made something of my life!”

The type of complaint Douglas shared with me is very common and is becoming more frequent within our interconnected world. Instead of being able to accept and enjoy the blessings God has given us, we compare ourselves to others, especially people from our peer group.

Comparing ourselves with others isn’t always wrong, especially if it leads us to imitate the behavior of role models like Christian heroes and saints (1 Cor. 11:1). Moreover, comparing ourselves to others can help us maintain humility about our own talents and accomplishments, as we take inspiration from others who have made further progress than us. However, much of the time we compare, it serves no positive purpose but blocks us from experiencing contentment. Instead of being content with the gifts God has given us (1 Tim. 6:6), we begin envying the possessions, lifestyle, wealth and opportunities God has bestowed on others.

Over the years, psychologists and economists have done a lot of research on the neurological and behavioral impact of comparison. Their research shows that by comparing ourselves to others, we sabotage our own happiness and make detrimental decisions. Here is a smattering of some of this research.

- Comparison Influences Spending and Saving Habits. Economists have found that our attitude towards spending and saving tends to be dictated, not by our actual income, but by our income in relation to others around us and in relation to our own past peak income.

- Income Comparison Leads to Unhappiness. Data published in 2010 from a Europe-wide survey found that people who compared their incomes to others were less happy with what they had. The comparisons that were most damaging to happiness occurred when people compared their incomes to friends from school and university.[xii] Other research conducted in other contexts found that social comparisons in an “upward” direction (that is, when we compare ourselves to people we deem superior to us) is associated with decreased self-esteem and decreased wellbeing.[xiii]

- Social Media Breeds Envy. A study published in The Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology showed that the more time someone spends on Facebook the greater likelihood there is that the person will compare herself to others and experience depressive symptoms as a result.[xiv] This type of comparison often happens on an unconscious level so that we are not always aware of the source of our depression. Another study, published in April 2015 in the same journal, found that individuals with low self-esteem were more likely to experience envy when viewing attractive Facebook profiles.[xv]

- Unhappy people enjoy seeing other people miserable. Unhappy individuals tend to increase in self-confidence when other people do worse,[xvi] and tend to conceive happiness as existing at other people’s expense, leading them to denigrate the fortunes of others.[xvii] Unhappy people tend to view happiness as a zero-sum game, whereby we are endlessly competing with those around us.[xviii] This social comparison model of happiness (happiness equals what I get minus what others get) leads many people to actually prefer less optimal outcomes in order to be above other people.[xix] By contrast, research shows that joyful people tend simply to enjoy what they are given without comparing themselves to others. While a miserable person actually enjoys seeing other people be miserable (misery loves misery’s company), a joyful person is able to delight in the good fortune of others, even when he has not been similarly blessed.

When we let go of the need to compare, then instead of thinking of happiness as a zero-sum game, or as a competition between us and our peers, we can develop the mentality of shep naches (happiness at another’s success). One of the tragic things about comparison is that it causes us to lose out on the vicarious happiness we might otherwise enjoy when reflecting on the blessings God has bestowed on others. Instead of feeling envy that Shelly was able to take her family on a vacation this summer, we can rejoice for her family’s good fortune. We can feel happiness that God blessed the Johnson’s with so much wealth. We can thank God for giving Dan such a lovely wife and so many children. By dispensing with comparison, we can begin truly to rejoice in other people’s good fortune. Indeed, a person who can train himself to be grateful for other people’s fortune and well-being, has continual grounds for happiness even when everything is going wrong in his own life.

Mind-Reading

- Eric’s father constantly criticized him. Now that Eric is in his young twenties, he finds it hard to believe he is lovable. When his fiancé, Annette, is tired or less bubbly than usual, Eric becomes suspicious and begins imagining that Annette is cooling towards him.

- Michelle’s teenage son, Stuart, is going through a severe period of rebellion. When Michelle makes any sort of boundary for Stuart (for example, prohibiting drugs on the property or insisting that he doesn’t play rap music around his younger sister), he becomes abusive. On a handful of occasions, Stuart has even hit his mother. When he is being violent, Michelle thinks she knows what is really going on in Stuart’s mind, having convinced herself that the real reason her son is violent is because he loves her. “After all,” Michelle rationalizes, “because he loves me, I’m the only person he feels comfortable really being himself around, which is why he takes out his frustration on me in the form of violence.”

- When the Leah and Matthew Walker lived in Montana, no one at their church ever questioned their decision to homeschool. Then the Walkers were forced to move to California for employment. In their new parish, Leah encountered a great deal of judgment from the other moms because her children weren’t in public school. Although no one ever asked Leah why she and Matthew were homeschooling, most people assumed they knew the answer: it was because they were afraid of the world, or because they wanted to over-shelter their children, or because they wanted to indoctrinate and control. In fact, the Walkers’ main reason for homeschooling was academic and had nothing to do with the various reasons people assumed.

- Miranda’s husband, Jackson, is always criticizing her. Earlier this week when Miranda made Jackson’s favorite meal for dinner for him, he replied, “You’re probably only doing that because you feel bad for how you treated me last night.” On Sunday when Miranda was hurrying the family to get ready for church, Jackson said, “The only reason you don’t want to be late again is because you’re worried what other people will think of you.” When Miranda challenges Jackson about these assumptions, he typically twists her words against her, using her explanations as a basis for a further accusation, such as “you’re just too sensitive”, or “gosh, why are you so defensive all the time?”

The common thread running through each of the above scenarios is some form of mind-reading. The thinking error of mind-reading occurs when we make assumptions about what another person is thinking, or when we prematurely assume we know what is driving someone else’s behavior. You have experienced mind-reading if you’ve even been with someone who overrode your explanations by announcing what you really meant, or who interacted with you as if he understood your thinking, motives and intentions better than you yourself.

Mind-reading is often practiced by people who suffer chronic insecurity, as in the case of Eric in the first example above. Often people who suffer from insecurity end up thinking things like, “she must have really thought I was stupid when I said that,” or “I just know everyone at the party was judging me.” When we fall victim to this type of mind-reading, we often fail to sufficiently distinguish the intent of someone’s behavior from the impact of their behavior, fallaciously inferring the former from the latter.

Mind-reading can also be practiced by people who are enablers, as in the case of Michelle when she convinced herself that the real reason her son was hitting her was because he loved her. It’s easy to read into someone else’s behavior those interpretations that make us feel better, even if this ends up subsidizing problems we need to be addressing.

Mind-reading is also a way of leveling judgment and condemnation on others, the case of the hostility levelled against the Walkers at their California church.

When mind-reading becomes chronic, a person may end up habitually twisting another person’s words to confirm their preconceived interpretations, making authentic communication impossible. Sometimes this can spill into verbal abuse, as in the case of Jackson and Miranda.

Since the majority of human communication is non-verbal, it is inevitable that we pick up implicit meanings and that we will interact with people by intuitively reading between the lines. This is a form of cognitive empathy and it should be distinguished from the thinking error of mind-reading, which involves premature or rigid assumptions about what someone is thinking. One way to distinguish between cognitive empathy and mind-reading is to observe the impact your behavior has on the other person. If you have empathic accuracy towards someone, this helps the other person to feel heard and understood, while fostering their sense of connection with you. By contrast, mind-reading blocks healthy connection, making the other person feel trapped in misunderstanding.

The more you get to know someone, the more temptation there is to second-guess what that person is thinking. Although this is a natural and beautiful part of having a close relationship, it can also spill into mind-reading. To illustrate this, imagine the following scenario.

Steve returned home after a long and tiring day at work. His wife, Jennifer, had also had a long day. She had intended to have a warm dinner waiting for her husband, but all day she had been harried by unexpected distractions. When Steve came home, all that was waiting for him was a big pile of dishes. A few minutes after his arrival, Steve asked Jennifer, “What did you do today?”

Angrily, Jennifer responded, “You only asked that because you want to know why I didn’t make dinner! You aren’t actually interested in my day at all.”

In this exchange, Jennifer is mind-reading since she is imposing a narrative onto Steve’s words that may not be accurate. Steve certainly might have been asking his question as a subtle way of finding out why there was no dinner, or maybe he was genuinely interested in Jennifer’s day. It may even have been a combination of both. Whatever may have been Steve’s real meaning, it would have been better for Jennifer to respond with another question, perhaps asking something like, “Honey, are you asking that because you are genuinely interested in how my day went, or only because you want to know why I didn’t have dinner waiting for you?”

Again, the point is not that we can never read between the lines to pick up non-verbal cues. Often we really do intuit what other people are thinking, especially people we know well. But even when you are pretty sure you know what another person is thinking, hold it lightly and don’t be afraid to check in with the other person.

Mind-Reading and Verbal Abuse

Have you ever come away from a conversation feeling like you didn’t know who you were anymore, yet without really understanding why? Have you ever had an interaction where the other person remained outwardly pleasant and respectful, and yet you came away feeling negated, or maybe even feeling like you were drawn into an alternative reality? If the answer is yes to any of these questions, then you may have been interacting with someone who used mind-reading as a form of verbal abuse.

A pervasive myth is that verbal abuse is limited to emotive behaviors like yelling, name-calling, and criticism. But a far more damaging—though less understood—form of verbal abuse occurs when a person twists another’s words or viewpoints to fit within categories they can comfortably manage and control. This could involve the abusive person imposing a false context onto the victim’s words, or it might simply involve making observations like, “the only reason you don’t want to talk about that is because you don’t have an answer,” or “I know what you were really thinking when you said that, and that’s why I’m ending this conversation right now.” These types of verbal jabs are do not necessarily signal the presence of abuse and can often be worked through with communication and repentance. But mind-reading does signal abuse when connected to a larger profile of control.

Control is not just about being bossy or achieving one’s will through domination. Control involves defining the other person, and a refusal to let the other person be herself. Mind-reading is one of the most common mechanisms in the controlling person’s toolbox. The controlling person defines the other person, telling her what she thinks, what her motives are, how she feels. In short, he defines who she is. The victim may feel mentally suffocated, squeezed into a fantasy world of her partner’s making. The impact of this abuse is even worse than criticism, for while criticism tears down another person’s actions or beliefs, this type of mind-reading tears down a person’s very sense of self. The victim in this type of a relationship typically tries desperately to defend herself, to explain, and to pacify her partner. However, once you begin engaging with this particular type of verbal abuse, you have already lost. As soon as you try to defend yourself (“no, I didn’t mean that, please let me explain”) you have already come into the orbit of the person who is trying to control you. You may even find your additional explanations being used against you.

Someone who uses mind-reading as a form of abuse may appear respectful, thoughtful, and even charming to the outside world, and yet people go away from conversations with him or her feeling negated and maybe even feeling like they have temporarily lost their sense of self. If the victim tries to explain about this to others, she may have trouble being believed. If she tries to bring these problems to the table, the abuser will typically blame the victim, piling on guilt and manipulation until she stops.

To learn more about the role that mind-reading plays in verbal abuse, see Patricia Evans book Controlling People.

Catastrophizing

Catastrophizing is closely related to emotional reasoning (see above) and involves inferring a dramatic pattern from insignificant events or forecasting the worst possible outcome to a situation. For example, we may be tempted to put a catastrophic context around our own shortcomings (“the fact that I did that means I’m a complete failure as a mother”), or to dramatize other people’s mistakes (“the fact that my wife believes that about me just proves we’re incompatible”) or to jump to extreme conclusions from a single incident (“only a manipulative and controlling husband would say that to me.”)

One of the most common forms of catastrophizing is when we forecast disastrous consequences about the future. Here are some common examples of catastrophic forecasting:

- “the fact that I can’t pay this bill proves we’re on the road to bankruptcy.”

- “if I compromise with my wife in this one area, then everything I’ve worked to achieve in our marriage could begin crumbling.”

- “things have gone so smoothly for so long that tragedy is bound to be just around the corner.”

Catastrophizing often hinders us from taking appropriate action since it leads us to underestimate the role we can play in overcoming problems and finding creative solutions to challenging circumstances.

It can be particularly easy to fall into the error of catastrophizing during times of stress, heartache, physical illness, or sleep deprivation. When you find yourself beginning to think catastrophic thoughts, the key is to recognize the error and remind yourself that you don’t need to go down that path. It is always possible to reframe catastrophic-based thoughts with a more realistic assessment of a situation. For example, instead of saying to yourself, “I think this is finally going to push me beyond coping point,” you could say, “I know from the past that I’ve been able to endure a lot more than I thought I’d be able to.” Instead of reflecting on how bad things are for you right now, you might could think, “Given everything I’m up against, I think I’m actually doing pretty well right now.”

One very effective way to combat catastrophizing is to imagine the worst possible outcome to a situation (i.e., the thing you are most afraid of happening) and then to remind yourself that even if this happens, you will still be alive, and God will still be there to help you grow through the suffering. As George MacDonald put it, “the best way to manage some kinds of painful thoughts, is to dare them to do their worst…and you find you still have a residue of life they cannot kill.”[xx]

When Ingrid was worried about losing her job, she began catastrophizing in her mind. This created such high levels of anxiety that she could hardly function. But then she paused and asked herself, “If I do lose my job, I am not going to starve. I will still have my loved ones. And most of all, God will still be there to help me grow through life’s trials.”

While Jess doing his taxes, he began catastrophizing about making a mistake. But then he stopped and reflected, “Even if I do make a mistake on my taxes, is it really going to be the catastrophe I’m worried about? Is it going to kill me? Is it going to ruin the life of my loved ones? Will the Lord turn His back on me?”

Another way to buttress ourselves against a catastrophizing mentality is to recognize that whatever difficulties we may be going through (including genuine catastrophes), it is a normal part of being human. Recognizing this can help us not succumb to a catastrophizing attitude even in the midst of genuine disasters. As Jordan Peterson reminds us, “it is a rare person indeed who isn’t suffering from at least one serious catastrophe at any given time—particularly if you include their family in the equation.”[xxi]

Remember, no disaster has the power to disrupt our inner peace unless we let it. We cannot control what is happening around us, but we can control our reactions.

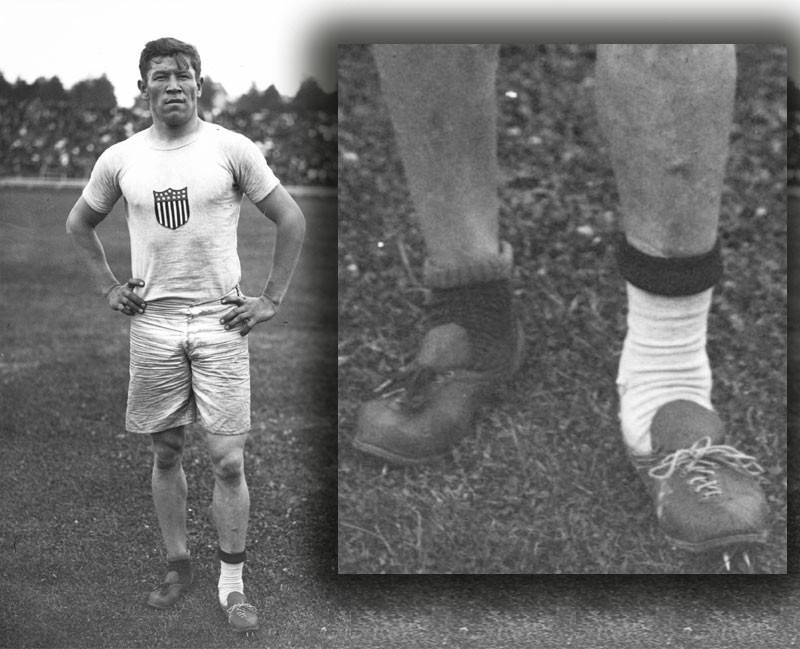

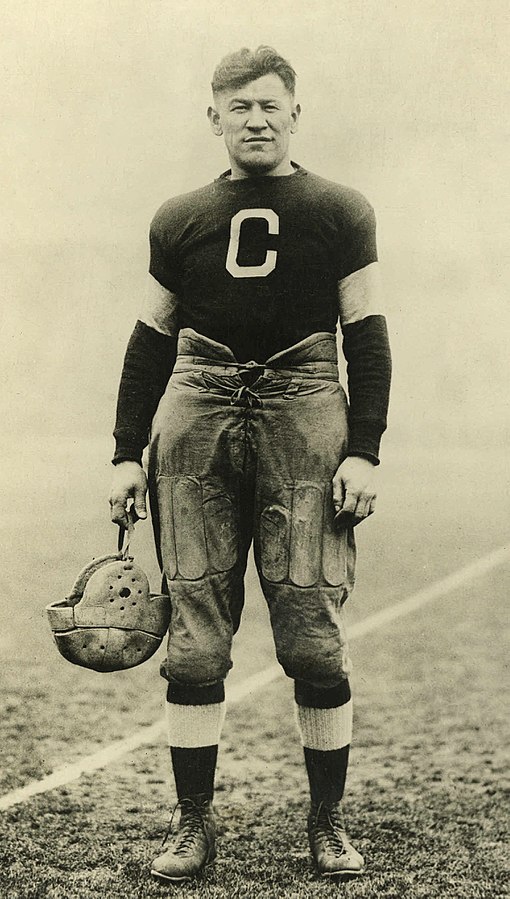

One person who has inspired me not to surrender to a catastrophizing attitude is the sporting take0legend Jim Thorpe (1887–1953). Thorpe was one of America’s most extraordinary athletes, with a career that involved success in football, various track and field events, baseball, and even basketball. Throughout his career, Jim experienced numerous setbacks that could easily have resulted in a catastrophizing mentality. Some of these setbacks included his twin brother dying when he was nine, being orphaned as a teenager, and being raised as a ward of the government. Yet throughout all these difficulties, he refused to give into a defeated attitude or a victim mentality.

Jim’s resilient attitude was manifested one afternoon in 1907 when he showed up on the field where the football team for his college, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was practicing. Although Jim was the school’s best track and field athlete, he wasn’t satisfied: he also wanted to play football.

“Go away and come back when you have some meat on your bones,” the trainer Wallace Denny replied in response to Jim’s request to play football.[xxii]

When it became clear that Jim wouldn’t take no for an answer, the team’s coach, “Pop Warner,” reluctantly agreed that Jim could help the men work on their tackling. The idea was simple: Thorpe was instructed to take the ball and run into a line of men, each standing around five feet from the next, so they could have practice tackling. But Jim had other plans. Wanting to prove himself, Jim shot right through the line of defenders to the touchdown line. After making his way through an entire line of defenders twice in a row, Jim was allowed a spot on the team for the upcoming season.

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School football team had to overcome prejudice about Native Americans—often stereotyped as “lazy and easily discouraged”—as they strove to compete as equals with the nation’s top schools.[xxiii] With Jim playing as a running back, the team managed to win the national collegiate championship in 1911, proving that Native Americans were just as capable of playing football as white people.

The next year, Jim had the opportunity to represent America in track and field at the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden. Once again, Jim faced enormous odds. Since Jim was a Native American, the United States government did not consider him to be a full citizen. (It wasn’t until 1924 that Congress granted full citizenship to Native Americans.) Thus, Jim’s legal status was a ward of the state. This meant that while Jim could represent America at the games, he was not allowed to control his own money and could not access funds that were available to the other athletes on America’s team. When Jim telegraphed the government agent at his reservation asking for $100 to help finance his trip to Stockholm, the agent replied that Jim should stop “gallivanting around the country” and return to the reservation to work on his land allotment.[xxiv]

At Stockholm, Jim won a string of medals and set numerous Olympic records. Despite being labelled by the media as “the greatest all-around athlete in the history of sports,”[xxv] Jim he was so poor that he did not even have a pen to sign autographs with.

Jim continued to suffer setbacks that could easily have resulted in a catastrophizing attitude. In 1913, newspapers discovered that Jim had played minor league baseball in the summer of 1909 and 1910. This meant that he was officially a “professional” athlete, even though he had played for meagre pay. This disqualified Jim from the Olympics according to America’s strict rules of amateurism that persisted at the time. (It was common for Olympic athletes to play minor league baseball in the summer, but they usually did it under fake names to preserve their amateur status.) Consequently, the Olympic committee decided to retroactively strip Thorpe of his honors. Someone even snuck into Jim’s room to steal his gold metals and send them back to Sweden. To this day, Jim Olympic records still do not appear in the Olympic annals, although his Gold medals have been posthumously awarded back to him.

In his later career, Thorpe entered professional sports with gusto. He played more baseball, as well as being a success in the newly established professional American Football League, which later evolved into the NFL. He even played on a professional basketball team from 1927–28.

Throughout his sporting career, Thorpe had numerous opportunities to surrender to a spirit of catastrophizing and victimhood. But instead he chose to persevere against tremendous odds, always pushing ahead towards the next goal.

My favorite story about Jim goes back to the time when he was competing at the Olympics in Stockholm. Before one of his events, somebody stole his shoes. Jim was penniless and couldn’t afford to just go into town and buy a new pair. Instead of giving into defeat, he simply rummaged through garbage cans until he found shoes people had thrown away. The shoes he found were not a matching pair and both were of different sizes, yet Jim put them on anyway to compete. Since one of the shoes was too large, he made up for that by wearing extra socks.

With these throw-away shoes, he went on to win Gold.

Take-Home Points

- Our emotional responses are largely conditioned by how we interpret our experiences.

- You have a specific part of your brain, just above your forehead, that has the task of weeding out thinking errors. The more you use this part of the brain, the better it will become at doing its job.

- By dispensing with unhealthy comparisons, you can achieve great joy by appreciating the blessings God has given to others.

- When you think you know what someone else means, don’t be afraid to ask. You may often find that your assumptions are wrong.

- There is a difference between experiencing a catastrophe vs. surrendering to a catastrophizing mentality. Disasters that happen around us do not have the power to disrupt our inner peace unless we let them.

References

[i] MacDonald, Unspoken Sermons Second Series, 131.

[ii] MacDonald, Annals of a Quiet Neighbourhood, 203.

[iii] Rod Dreher, How Dante Can Save Your Life: The Life-Changing Wisdom of History’s Greatest Poem (New York, NY: Regan Arts, 2015), 66.

[iv] Dreher, 234.

[v] For some specific examples of how much of what we perceive in life is ambiguous and open to a variety of interpretations, see my earlier article, “Gratitude as a Way of Seeing.”

[vi] Epictetus, Enchiridion, or Manual (South Bend, IN: Infomotions, Inc., 2000), 2.

[vii] Caroline Leaf, Switch On Your Brain: The Key to Peak Happiness, Thinking, and Health, chap. 1.

[viii] Fr. George Morelli, “Mindfulness as Known by the Church Fathers.,” Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America, ww1.antiochian.org/mindfulness-known-church-fathers, accessed March 16, 2000.

[ix] For background on Baxter’s life and ministry, see Phillips, Saints and Scoundrels, chap. 7.

[x] Richard Baxter, The Practical Works of Richard Baxter (London: J. Duncan, 1830), 118–19.

[xi] George MacDonald, The Marquis of Lossie, The Sunrise Centenary Editions of the Works of George MacDonald (Eureka, CA: Sunrise Publishers, 1877), 375.

[xii] Emma Wilkinson, “Comparing Salaries Leads to Blues,” BBC News, May 29, 2010, www.bbc.com/news/10182993, accessed March 16, 2000.

[xiii] Jin-Liang Wang et al., “The Mediating Roles of Upward Social Comparison and Self-Esteem and the Moderating Role of Social Comparison Orientation in the Association between Social Networking Site Usage and Subjective Well-Being,” Frontiers in Psychology 8 (May 11, 2017).

[xiv] Mai-Ly N. Steers, Robert E. Wickham, and Linda K. Acitelli, “Seeing Everyone Else’s Highlight Reels: How Facebook Usage Is Linked to Depressive Symptoms,” Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 33, no. 8 (October 1, 2014).

[xv] Helmut Appel, Jan Crusius, and Alexander L. Gerlach, “Social Comparison, Envy, and Depression on Facebook: A Study Looking at the Effects of High Comparison Standards on Depressed Individuals,” Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 34, no. 4 (April 1, 2015): 277–89.

[xvi] In 1997, Sonja Lyubomirsky, who teaches psychology at the University of California Riverside, teamed up with Lee Ross from Stanford, to explore the different ways happy and unhappy people responded to positive and negative feedback following a teaching exercise. They found that positive feedback enhanced the self-confidence of happy participants even if the happy person learned that their peers got a better result. On the other hand, unhappy people increased in self-confidence when they received positive feedback alone, but increased only minimally when they learned their peers did better. However, the really interesting part of the study was when participants were given negative feedback and told that their peers did even worse. During this part of the study unhappy participants showed greater increases in self-confidence after learning that they did poorly than after learning that they did well, because in the former case they were told that their peer did even worse than them, and in the latter case they were told that their peer did better. By contrast, for the happy participants, the condition of doing well while their peer did better resulted in more self-confidence than when they learned that they did poorly but that their peer did worse. S. Lyubomirsky and L. Ross, “Hedonic Consequences of Social Comparison: A Contrast of Happy and Unhappy People,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73, no. 6 (December 1997): 1141–57.

[xvii] S. Lyubomirsky and L. Ross, “Changes in Attractiveness of Elected, Rejected, and Precluded Alternatives: A Comparison of Happy and Unhappy Individuals,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76, no. 6 (June 1999): 988–1007. Elizabeth Weil described the import of this experiment for The New York Times: “Dr. Lyubomirsky designed an exeriment in which people ranked 10 desserts, knowing they’d get one. Each participant was then given his second or third choice and told to rank all 10 desserts again. …Dr. Ward remembered, ‘The happy people said, “Well, this dessert is good, and I’m sure the others are good, too!” The unhappy people liked their desserts just fine but indicated they were extremely relieved not to have received the ‘awful’ nonchosen dessert. In other words, unhappy people derogated the dessert they did not receive, whereas happy people felt no need to do so.’” Elizabeth Weil, “Happiness Inc.,” The New York Times, April 19, 2013 accessed August 30th, 2019, www.nytimes.com/2013/04/21/fashion/happiness-inc.html, accessed March 16, 2000.

[xviii] Dr. Lyubomirsky did work with children and found that unhappy children had unconsciously imbibed the notion that the only way to achieve true happiness is at another person’s expense. As The New York Times explained, “Dr. Lyubomirsky asked two volunteers at a time to use hand puppets to teach a lesson about friendship to an imaginary audience of children. Afterward the puppeteers were evaluated against each other: you did great but your partner did better, or you did badly but your partner was even worse. The volunteers who were happy before the puppeteering review cared a bit about hearing that they had performed worse than their colleagues but largely shrugged it off. The unhappy volunteers were devastated. Dr. Lyubomirsky writes: ‘It appears that unhappy individuals have bought into the sardonic maxim attributed to Gore Vidal: “For true happiness, it is not enough to be successful oneself. … One’s friends must fail.” This, she says, is probably why a great number of people know the German word schadenfreude (describing happiness at another’s misfortune) and almost nobody knows the Yiddish shep naches (happiness at another’s success).” Weil, “Happiness Inc.”

[xix] The irrationality of social comparison emerged in a study conducted at Harvard. “…students at the Harvard School of Public Health were asked to choose in which of two worlds they would prefer to live. In World A, your current yearly income is $50,000 and others earn $25,000. In World B, your current yearly income is $1000,000 and others earn $200,000. Which one would you choose? A majority of the students preferred World A in spite of it providing half the income available in World B, presumably because their relative income position was higher. This same answer pattern was given for several other domains of life, such as intelligence and attractiveness. Again, people prefer lower absolute levels as long as they have an advantageous relative standing.” Manel Baucells and Rakesh Sarin, Engineering Happiness: A New Approach for Building a Joyful Life (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2012), 51.[xx] George MacDonald, Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women (London: Smith, Elder, 1858), 92.

[xxi] Jordan B Peterson, 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos (Toronto: Random House Canada, 2018), 316.

[xxii] Steve Sheinkin, Undefeated: Jim Thorpe and the Carlisle Indian School Football Team (New York, NY: Roaring Brook Press, 2017), 110.

[xxiii] Sheinkin, 68.

[xxiv] Sheinkin, 170.

[xxv] Sheinkin, 181.