My previous post, “A Visit From G..K. Chesterton“, raised the issue of what is often referred to as “the sacramental imagination.” Along with other poets and novelists associated with the sacramental imagination (one thinks of authors like George Herbert, George MacDonald, Gerard Manley Hopkins, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien), Chesterton invited his readers to look at the world in a new way, to see the divine splendor that lies concealed in the stuff of ordinary life.

My previous post, “A Visit From G..K. Chesterton“, raised the issue of what is often referred to as “the sacramental imagination.” Along with other poets and novelists associated with the sacramental imagination (one thinks of authors like George Herbert, George MacDonald, Gerard Manley Hopkins, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien), Chesterton invited his readers to look at the world in a new way, to see the divine splendor that lies concealed in the stuff of ordinary life.

Chesterton believed that we can best approach this sacramental vision by becoming like little children. He pointed out that as we mature we often lose the sense of wonder towards the world that came to us naturally when young. Taking inspiration from St. Francis of Assisi, Chesterton believed that the spiritual life was an invitation to regain this elemental sense of wonder, to have our spiritual senses sharpened so that we can begin seeing the halo of sanctity in all natural things. “…the whole philosophy of St. Francis”, he reflected, “revolved around the idea of a new supernatural light on natural things, which meant the ultimate recovery not the ultimate refusal of natural things.”

A Word About “Sacrament”

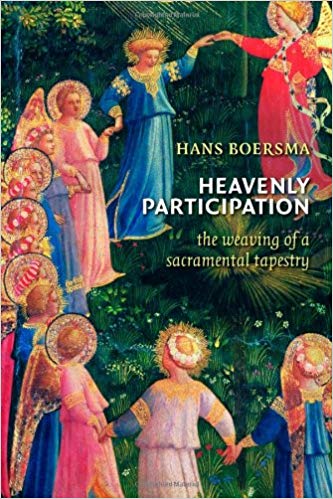

I realize that the word “sacramental” may be problematic for some, perhaps bringing to mind confusing concepts like transubstantiation, or controversies between Catholics and Protestants at the time of the reformation. We can safely set aside all such controversies since I am using the term sacrament in a way that all Christians—Protestant, Catholic and Eastern Orthodox alike—should be able to accept. The best definition of sacrament, at least in the historic sense that I am using the term, comes from Hans Boersma, who currently serves as the J. I. Packer Professor of Theology at Regent College. In his 2011 book Heavenly Participation, Boersma summarized the sacramental lens through which the early church viewed the world:

“For the patristic and medieval mindset…the world was, as the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins famously put it, “charged with the grandeur of God.” Even the most basic created realities that we observe as human beings carry an extra dimension, as it were….

Throughout the Great Tradition, when people spoke of the mysterious quality of the created order, what they meant was that this created order – along with all other temporary and provisional gifts of God – was a sacrament. This sacrament was the sign of a mystery that, though present in the created order, nonetheless far transcended human comprehension. The sacramental character of reality was the reason it so often appeared mysterious and beyond human comprehension.”[i]

Boersma continued by explaining that sacraments are not simply signs pointing towards the spiritual dimension; rather “sacraments actually participate in the mysterious reality to which they point.” [ii]

We can understand sacraments further by reflecting on those occasions when God has been especially near to us. Although God is with us all the time (Psalm 139:8), some of us have had the experience—or perhaps have read about others having the experience—of God manifesting Himself in a special way. During such times, it is as if part of the world becomes temporarily charged with special grace, allowing us to experience God more directly. We read about this occurring when Moses met God at the burning bush, or when Elijah stood before God on Mount Carmel, or when Jesus was transfigured on the mountain, or when Paul describes how he was caught up to the third heaven and “heard inexpressible words, which it is not lawful for a man to utter.” (2 Cor. 12:4) During these experiences, God draws near to men and women in a special way, transforming ordinary earthly things—like a bush, a mountain, a human being—into occasions of special glory, radiance and grace.

We normally think of such experiences as God intervening in a special way to make Himself present to us, or perhaps we might describe it has the natural being overcome by the supernatural. But ancient Christian reflections on the Transfiguration suggest that experiences like these enable us to glimpse a reality that is already inherent within our world but which we are not normally equipped to see.[iii] During such times, the veil separating us from the spiritual dimension is temporarily pulled back, enabling us a glimpse realities that penetrate to the heart of how things actually are.

We see something like this happening in an event recounted in 2 Kings 6. While making war against the people of God, the king of Syria constantly found his plans frustrated because of the prophetic insight of Elisha. Whenever the Syrian king planned to attack at a certain place, God revealed it to Elisha who promptly warned the king of Israel. Eventually the Syrian king learned from his servants what was going on. His response was to send a large force to surround the city where Elisha was staying. When Elisha’s servant arose early the next morning and saw an army encircling them, he went to Elisha and exclaimed, “Alas, my master! What shall we do?” (2 Kings 6:15).

Elisha answered, “Do not fear, for those who are with us are more than those who are with them.” (2 Kings 6:16). Elisha was not referring to human strength but to divine assistance. Elisha was able to perceive the spiritual realities that the young man could not, including a host of angelic warriors. Verse 17 tells us what happened next:

“And Elisha prayed, and said, ‘Lord, I pray, open his eyes that he may see.’ Then the Lord opened the eyes of the young man, and he saw. And behold, the mountain was full of horses and chariots of fire all around Elisha.” (2 Kings 6:17)

This passage gives us an important insight into the nature of Elisha’s prophetic ministry. We often think of a prophet as someone who is able to see into the future and accurately predict what is going to happen. But this passage points towards an even more important aspect of the prophetic ministry: an ability to see the world with spiritual eyes. Elisha knew nothing of the modern dichotomy between the natural and the supernatural, the physical and the spiritual, the sacred and the secular: to him, everything was permeated with the presence of God. Using the language of later Christian theology, we could say that Elisha was able to see things sacramentally, to know that “the most basic created realities that we observe as human beings carry an extra dimension, as it were.”[iv]

Throughout history Christian theologians have taught that part of what it means to grow in Christian maturity is to develop spiritual eyes for perceiving things in a new way. This does not refer to being able to see angels like Elisha, though this has certainly occurred in some people’s experiences. Rather, Christian theologians have emphasized that to grow in maturity involves becoming attuned to the spiritual realities that underlie the commonplace, from our family relationships to our daily routine, from our inner thoughts to our deepest desires, from our lying down to our waking up. God is part of all these experiences, yet often we fail to perceive it until our eyes are opened, like the eyes of Elisha’s servant were opened.

Consider the example of sleep. Sleeping is a process we might be tempted to call “secular”, in contrast to “spiritual” activities like going to church or reading the Bible. Yet Psalm 127:2 tells us that God grants sleep to His beloved, while Psalm 3:5-6 tells us that when we sleep and wake up, God is the one sustaining us. What would our nights be like if we really believed that?

Or take the example of relationships. Whenever a member of your family or church asks you for help, it is actually Christ you are helping (Mt. 25: 35-40), as surely as Simon of Cyrene helped Christ by carrying His cross (Lk. 23:26). What would our relationships be like if we truly believed this? We often fail to notice Christ’s presence because He comes to us disguised in our commonplace relationships, including relationships that may irritate and annoy us.

What about something as basic as breathing? Scripture is clear that our breath comes from God (Is. 42:5) and that every breath we take can be an opportunity for mindful awareness of God’s presence within.

To these examples we might add numerous others. The point is that when we begin viewing the world sacramentally, we start to recognize that ordinary things are enchanted with God’s presence.

The clearest examples of ordinary things being conduits of God’s presence appears in the New Testament’s teaching on the sacraments of baptism and the Eucharist. Yet it is precisely when we approach these specific rites that a question occurs to many. If we view the entire world sacramentally, then do specific sacraments like baptism and the Eucharist lose some of their significance by becoming just more of the same? If everything is sacred, then is nothing sacred in a particularized sense? Throughout the last 500 years, Christians have struggled with these types of questions. Some Christian traditions have attempted to preserve God’s presence throughout all of creation by downplaying His particular presence in specific practices or objects. One thinks of the way the Puritans made it against the law to celebrate special holidays like Christmas, because they wanted to emphasize that every day is holy.

We get a glimpse of a solution by reflecting on God’s presence in the temple in the Old Testament. God was present in the Holy of Holies in a way that He was not present in the temple’s outer court, and He was present in the outer court in a way He was not present in ordinary tents and houses. Similarly, when God’s people were wandering in the wilderness, God was present to them in a pillar of cloud in a way He was not present in ordinary rain clouds. But here’s the important point: God’s particular presence in the tabernacle of the wilderness and later Solomon’s temple did not negate His presence elsewhere, but rather established it. We learn this by the fact that the Old Testament descriptions of God’s special presence in the tabernacle and temple always pointed towards God’s more general presence in all of creation. This came into fuller focus when God took on our material flesh and began to embody temple functions within in His own ministry.[v] When the veil of the temple was ripped from top to bottom, “the boundary between sacred and profane was torn apart” signifying that “holiness dwells in everyday things.”[vi]

We see a similar principle at work in the descriptions of God’s special presence in the particular nation of Israel. Scripture continually makes clear that God’s election of Israel was meant to serve as a template for understanding His purposes for all the nations of the world.

Again and again through the Bible we see that God’s particular work in one time and place becomes the basis for understanding His relation to the entire world. Certain things and places are sacred in a particular sense, but this establishes rather than negates God’s more general presence elsewhere. This might be compared to the way a man, after getting married, finds himself having a new respect for all women, or the way a woman may have a greater appreciation for all children after becoming a mother.

If we take this same principle and apply it to Christian sacraments, it begins to make sense why Christian thinkers frequently point out that God’s special presence in sacraments like baptism and communion can become a template for understanding His mysterious presence throughout the entire world. Just as grace transforms nature in the case of the bread and wine of the Eucharist so that they are no longer merely ordinary bread and wine (though the mechanics of what actually goes on remain open to speculation), so God’s grace also transforms all of nature, including the commonplace realities of our everyday lives.

A Word About “Imagination”

It’s time now to clear away the brush surrounding another term. Learning to perceive God’s presence in and through the commonplace is something I have referred to as the “sacramental imagination.” I realize, however, that the term “imagination” may be difficult for some. Let me be clear that by “imagination” I do not mean fantasizing, nor do I mean thinking things that are false. Rather, I am using the term similar to how it has been used by Christian philosophers like Charles Taylor[vii] and James K.A. Smith,[viii] as a lens through which we perceive and interpret the world around us and map our experiences within it.

To understand the role of imagination in mapping our experiences, it may be helpful to reflect on how we perceive and interpret everyday objects like chairs and beds. There is a great deal of difference between perceiving a chair as merely a piece of furniture vs. an aesthetic object, which are both different to perceiving a chair as a place where I will be confined. In each case, the chair may look the same while having an entirely different meaning. Similarly, there is a difference between perceiving a bed as the place where I experience insomnia vs. a place that has been carefully prepared for love-making. In all such cases, the same object is being perceived, but the difference comes down to how we “imagine” it. Through imagination we map a sense of meaning onto our experiences.

It is inescapable that we “imagine” our experience in one way and not another. The important question is whether we imagine our experience in a way that leads us closer or further away from the truth. If I imagine an unborn child as “a lump of tissue” or “the heir to the throne of England,” both descriptions may be true in a purely technical sense, but each invite us to think differently about the child, and one description may be closer to the actual shape of reality than the other.

C.S. Lewis explored many of these ideas in his writings since his conversion to Christianity not only involved a shift of his intellect, but a shift in how he imagined the world. Prior to his conversation, his friend J.R.R. Tolkien had invited Lewis to imagine the world differently, even before his intellect caught up. “Tolkien helped Lewis to realise that the problem lay not in Lewis’s rational failure to understand the theory, but in his imaginative failure to grasp its significance.”[ix] In his biography of Lewis, Alister McGrath described the role that imagination played in nudging Lewis towards Christianity:

…there is a certain way of seeing reality that brings it into the sharpest focus, illuminating the shadows and allowing its inner unity to be seen. This, for Lewis, is a ‘realising imagination’—a way of seeing or ‘picturing’ reality that is faithful to the way things actually are.[x]

In the first book Lewis wrote after his conversation, titled The Pilgrim’s Regress, he conveyed something of this imaginative realignment. The main character of this story, John, has a vision of an island in the distance, for which he experiences an overwhelming longing. He sets out on a lifelong journal to find the object of his desire. Eventually, John reaches the land of his longings only to find that he had circumnavigated the globe and arrived at the other side of the Eastern mountains he had known all his life, the home of the Landlord. Lewis explains that John is finally able to see “the real shape of the world we live in.”[xi] For Lewis, the spiritual life is an invitation to see our earthly life in a new way. In his fiction, Lewis used strange creatures and fantastical lands to invite us to picture reality in a new way, so that through imagination we might actually grasp a truer sense of the real shape of the everyday world we inhabit.

That’s enough for one blog post, but I want to continue exploring the theme of the sacramental imagination in further articles.

Endnotes

[i] Hans Boersma, Heavenly Participation : The Weaving of a Sacramental Tapestry (Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans, 2011), 21–22.

[ii] Boersma, 23.

[iii] In a sermon on the transfiguration, the fourteenth-century saint, Gregory Palamas, declared that “in the teachings of the Fathers, Jesus Christ was transfigured on the Mount, not taking upon Himself something new nor being changed into something new, nor something which formerly He did not possess. Rather, it was to show His disciples that which He already was, opening their eyes and bringing them from blindness to sight.” Brian Daley, ed., Light on the Mountain: Greek Patristic and Byzantine Homilies on the Transfiguration of the Lord (Yonkers, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2013).

[iv] Boersma, Heavenly Participation, 21.

[v] On Christ’s appropriation of temple functions within his own ministry, see N. T. Wright, The Challenge of Jesus: Rediscovering Who Jesus Was and Is (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1999).

[vi] Joseph Ratzinger Cardinal, God Is Near Us: The Eucharist, The Heart of Life (San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2003), 99.

[vii] Charles Taylor, Modern Social Imaginaries (Durham, N.C: Duke University Press, 2004).

[viii] James K. A Smith, Imagining the Kingdom: How Worship Works (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2013).

[ix] Alister Mcgrath, C. S. Lewis: A Life (Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, 2016), 149.

[x] Mcgrath, 135.

[xi] C.S. Lewis, The Pilgrim’s Regress: An Allegorical Apology for Christianity, Reason and Romanticism (Glasgow: Collins, 1933), 222.

“For the patristic and medieval mindset…the world was, as the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins famously put it, “charged with the grandeur of God.” Even the most basic created realities that we observe as human beings carry an extra dimension, as it were….

“For the patristic and medieval mindset…the world was, as the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins famously put it, “charged with the grandeur of God.” Even the most basic created realities that we observe as human beings carry an extra dimension, as it were….