Last year I received an invitation to speak at a conference for professionals in the caring professions. The conference, which was attended by doctors, nurses, counselors, psychologists, psychiatrists, dentists, hospital and army chaplains, missionaries, marriage and family therapists, surgeons and students, was on the topic of pain and suffering. The conference organizers asked me to give a seminar on the topic “Gratitude During Times of Suffering” and my marching orders were simple: explain how it’s possible to remain thankful in the midst extreme of suffering.

Now I’ve never been particularly good at being thankful when things are going wrong. If I have trouble sleeping, I grumble the next day. If I don’t have enough money to buy something I want, I whine and complain to whoever will’; listen. If I have a physical injury, everyone in my circle of friends is sure to know about it. So expecting me to give a talk about practicing gratitude during times of suffering would be like asking ask John Wayne to dance Swan Lake, or asking Justin Bieber to sing the part for Count Almaviva in The Marriage of Figaro.

To put it bluntly, I found my assignment daunting. How could I teach other professionals a lesson I had not even mastered myself?

In the end I decided to study the people who had learned to be grateful in the midst of suffering and to see what lessons could be learned from their lives. Specifically, I decided to look at those who experienced the horrors of the Nazis and communists and yet somehow remained positive and optimistic throughout. What was their secret? And could the techniques they used for remaining positive in the midst of so much pain and misery help us better to cope with the mild inconveniences we face every day?

It turns out that their secret isn’t complicated at all. It all comes down to attitude.

I know, I know. You’ve already heard a hundred times that you need to maintain a positive outlook on life. After all, the self-help sections of the bookstores are filled with books essentially saying the same thing: be positive! If you read enough self-help literature, you can sometimes come away with the impression that maintaining a positive attitude is easy, as if there is a switch we can suddenly turn on to “have the right attitude.” The catch is that when someone tries to practice a positive attitude and can’t, then he or she feels worse than in the first place.

Part of the problem is that the self-help gurus who promote the just-be-positive approach usually live comfortable lives, having achieved a measure of worldly success. By studying those who lived on the other end of the spectrum, in conditions of extreme misery, we can look past the tired clichés to strategies of real substance. When we do, we find that living the Good Life does come down to attitude, but not in the way that is often supposed.

The Two-Part Formula for the Good Life

While reviewing the twentieth-century prison literature, I began to see that part of the problem is that we have come to think about attitude in the wrong way. Those who managed to remain grateful and positive in the midst of Nazi and Stalinist death camps understood two secrets that those of us living in comfort and ease are often prone to overlook. These secrets, which collectively amount to what I call the “good life formula”, are these:

- The things we can control in our internal environment are more fundamental to living the Good Live than the things we cannot control in our external environment.

- Meaning, not happiness, is what enables us to live the Good Life.

I want to spend the rest of this postunpacking these two points.

Inside vs. Outside

Linda was a mother of four in her thirties. When she and her husband Matt had their first child ten years ago, Linda had high hopes for the family. But over the next ten years, those hopes gradually dissipated. It started when Matt got laid off from his job and suffered through a long period of unemployment. It got worse when people in her church didn’t understand their decision to homeschool. Then Linda’s father died, following a period in which she gained thirty pounds. Linda became more and more unhappy. To make matters worse, Matt seemed to be growing distant from her. All he ever seemed to do in the evenings was watch TV. Whenever she asked Matt what was wrong, he didn’t want to talk.

One day Linda was sharing her problems with an elderly lady in her church named Meredith. Meredith’s husband had died three years earlier, and since then she spent her time mentoring younger women in the church, as well as helping to baby sit for some of the mothers. Meredith listened attentively to Linda’s problems, but then suddenly stopped her.

“I want to ask you a question Linda” she said. “What would you need in order to be happy?”

At first Linda was taken aback by the question and didn’t know how to respond. But Meredith persisted, even insisting that Linda make a list on piece of paper all the things that would need to change in her life before she could be happy.

“Don’t write down what you think the ‘correct’ or ‘spiritual’ answer is,” she said, “but just the first things that come to your mind. If you could change anything about your life to be happy, what would it be.”

Eventually, Linda wrote a list and handed it to Meredith to read.

Over the next few weeks, Meredith helped Linda to see that the things on her list—the price she had put on her own happiness—were largely things outside her control. With a few exceptions, most of the things Linda wanted to change were completely out of her reach since they depended on other people or circumstances changing. No wonder Linda felt trapped in a cycle of frustration and discouragement.

But then Meredith helped Linda see that there were other improvements she could make to her life that were within her control. For example, she could control the mindset she brought to the situations she faced. She could control the type of person she became in and through the daily challenges. She could control how she treated her husband, even when he was difficult. She could give thanks for the opportunities to practice patience in the face of difficulties. Above all, she could control her attitude.

Meredith helped Linda make a new list—a list of goals that were within her reach. These goals included keeping a gratitude journal, finding new and creative ways to serve her husband and kids, spending more time in the Word each day, and so forth. The list also included some practical ways she could be more proactive in her own health and wellbeing. But above all, Meredith helped Linda set some goals that involved changing her attitude through reframing how she looked at her life.

A month later, Linda came back to Meredith with astonishing news: focusing on the things she could change, and not worrying about the things she couldn’t, had been helping her have a more positive attitude about her situation. In fact, she was even beginning to feel happy again.

Meredith was delighted, but warned Linda not to get too focused on her own happiness. “If you’re happy, that is a byproduct of doing the right things—ultimately following Jesus. But never let happiness become your goal.”

Sometimes people aren’t ready to make the transition Meredith helped Linda to make. Sometimes we need to spend some time dwelling on our difficulties in order better to understand them, or even realistically to face problems after prolonged periods of denial. Sometimes we also need to have a listening ear to pour out our troubles to so we don’t feel alone. But Meredith must have sensed that Linda was ready to make the move to a more positive approach, one that shifted the focus away from struggling against factors in the external world that were out there, to working on internal factors within.

The story of Linda illustrates an important point that we often overlook. Living the Good Life depends, more than you might think, on factors you can control in your internal environment, while it depends less than you might think on factors in your external environment.

When I talk about our ‘internal environment” I’m referring to things like our mindset, our values and our core spiritual convictions. These are all things inside of us that we have control over and which largely determine our attitude. By contrast, things in our external environment are factors outside us that we don’t always have control over. This would include things like how other people treat us, what opportunities we have, what is happening around us in the larger world as well as in our immediate environment.

Most of the time, we tend to be like Linda and instinctively assume that a positive attitude occurs as the result of things working out for us in this second realm—the realm of factors external to us that we cannot always control. That is certainly what I thought before I started reviewing the twentieth-century prison literature. For example, if I had more money, more opportunities, a better job, a nicer house, more caring friends and family members, then it would be easy to have a good attitude. Or so I thought.

Sometimes we desire things that are genuinely unselfish and right: if only my son or daughter would come to know the Lord, if only so-and-so would stop treating me unkindly, if only God would heal my child of this illness, then I could have a positive attitude about my life. Regardless of whether our desires are self-centered or others-focused, carnal or spiritual, selfish or unselfish, the common assumption tends to be that the Good Life occurs as a symptom of things going well for us.

The problem is that by making the Good Life contingent on what is out there externally, we set ourselves up for perpetual frustration and misery. This perspective puts our wellbeing into the hands of others and events beyond our control.

In days gone-by, people never needed much reminding that most of what happened in the external world was outside their control. The survival of our ancestors often depended on outside factors like having the right weather, having access to sufficient food sources, and so forth. The irony is that as we’ve come to exercise more control over the external world, we’ve surrendered control of our internal realm, supposing that our emotional, psychological and spiritual wellbeing also depends on what is happening around us. In the midst of our rapidly expanding ability to manipulate the external world with technology, it’s sometimes easy to forget that the things that matter most in life—the ingredients that go into the Good Life—are still completely independent of anything happening in the external world. Rather, happiness and wellbeing are the results of our internal disposition. (“Internal disposition” is the intellectual way of referring to attitude.)

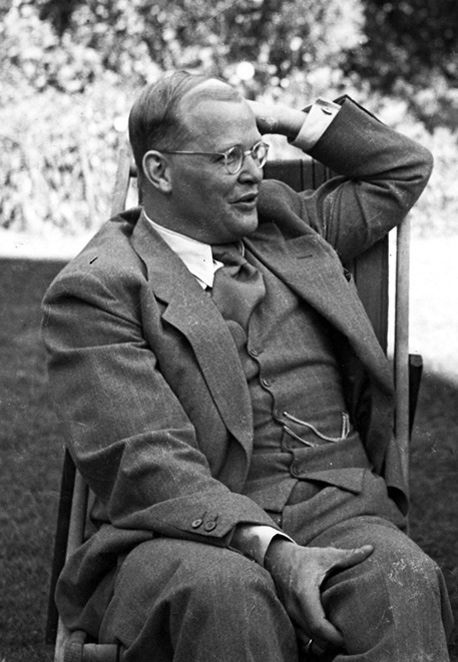

In my research I found that some—not all, but some—of those who suffered under the Nazis or Communists understood the crucial importance of their inner attitude. They understood that the things that matter most in life arise from the attitude we carry in our heart and mind—attitudes like gratitude, peace and love—no matter what is happening around us. In future posts I will share some powerful examples of this from the prison literature, but for now I will limit myself to a quotation from one of my favorite authors, Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945).

Just think about those powerful words for a moment: happiness depends so little on circumstances and so much more on what goes on inside us. Bonhoeffer understood that the Nazis could take away his job, his freedom, his friends, family and loved ones, and they could even take away his life; but the one thing they couldn’t take away was the attitude inside his heart. But does happiness even really matter? Bonhoeffer seemed to downplay his own happiness or unhappiness, asking, “Anyway, what do happiness and unhappiness mean? This leads to the second point that I found from the prison literature, which is that the pursuit of happiness (at least, in the modern sense of the term) is not what enables us to achieve the Good Life; rather, it is far more important to pursue a life of meaning.

(For the Greek philosopher Aristotle, as well as for many philosophers and theologians throughout the Middle Ages, “happiness” meant something very different to the contemporary meaning. Happiness was not conceived as a subjective state of mind associated with pleasurable sensations, but something more akin to Christ’s use of the term “blessed” in His sermon on the mount. Happiness was about living a life oriented towards virtuous goals. Because the word “happiness” has been debased in our culture, I find it easier to talk about a life of meaning instead. However, if “happiness” is understood in the more ancient sense, this coincides with my use of the term “meaning.”)

The Will to Meaning

Frankl saw that the ability to accept suffering with dignity and spiritual integrity, and the ability to find a higher meaning in and through the confusion and agony, could determine whether a prisoner literally shriveled up and died, or whether he continued to live. Being able to tap into inner resources of meaning was even more predictive of whether a prisoner would survive than the physical condition of that person upon entering the camp. Sensitive people of “a less hardy make-up” who possessed “a life of inner riches and spiritual freedom”, often “seemed to survive camp life better than did those of a robust nature.”[2]

The suffering in the death camps presented the prisoners with the same choice each of us face when confronted with suffering. Will we revolt against our circumstances, or find ways to grow in and through the hardships to become richer, deeper and more meaningful people? Frankl saw that revolting against hardships could take the form of bitterness, or it could take the form of passivity, hopelessness and emotional numbing. In all such cases, we miss the opportunity to grow deeper into a life of intense meaning. Only through meaning are we able to rise above what would otherwise be a hopeless situation.

It is through such heroic attempts to embrace a life of meaning, rather than the pursuit of personal happiness (in the modern sense of the term, at least), that the Good Life consists. In fact, a life of meaning often involves turning away from pursuing our own personal wellbeing for the sake of serving others. In one moving passage, Frankl told of those who, though starving to death, chose to give their last bits of precious bread to help others, and thus to realize the ultimate sacrifice of choosing to take up one’s cross for the sake of another. Such prisoners were able to add a deeper meaning to what would otherwise be a hopeless and purposeless situation.

But what does a life of meaning look like in practice? Frankl showed that a sense of inner meaning comes in many different forms, but it always involves attitude and decision. In the death comes, some people realized a higher meaning in the choice to accept their suffering instead of escaping into a condition of numbness and passivity. For some, spiritual freedom came in their refusal to give up hope, even when the likelihood of ever surviving the war seemed very slim. For others, meaning could be attained by choosing to practice gratitude, including thankfulness for little things we usually take for granted. For still others, meaning was realized in the decision to pour one’s last ounce of life into service to others.

“We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way. …in the final analysis it becomes clear that the sort of person the prisoner became was the result of an inner decision, and not the result of camp influences alone. Fundamentally, therefore, any man can, even under such circumstances, decide what shall become of him—mentally and spiritually. …the way they bore their suffering was a genuine inner achievement. It is this spiritual freedom—which cannot be taken away—that makes life meaningful and purposeful….

“The way in which a man accepts his fate and all the suffering it entails, the way in which he takes up his cross, gives him ample opportunity—even under the most difficult circumstances—to add a deeper meaning to his life.”[3]

Frankl was later able to use these insights in his work as a psychotherapist. He taught his patients that each of us have the power to bring meaning and purpose to our lives by how we interpret the circumstances that confront us. The quality of our life depends, not on everything working out well for us, but on our “will to meaning”—the determination to find meaning, purpose and significance through situations that might otherwise lead to hopelessness and depression.

I think the Apostle Paul must have had something like this in mind when he wrote to the Corinthians about finding positive meaning—which for Paul, is always rooted in Jesus Christ—in and through the tribulations he encountered.

“We are troubled on every side, yet not distressed; we are perplexed, but not in despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; cast down, but not destroyed; always bearing about in the body the dying of the Lord Jesus, that the life also of Jesus might be made manifest in our body.” (2 Corinthians 4:8-11)

Meaning vs. Happiness

This “will to meaning” does not involve blind optimism, nor does it involve putting an optimistic gloss over the difficulties we face. On the contrary, both Viktor Frankl and the Apostle Paul were very realistic about the sufferings they endured.

The will to meaning also does not involve pretending to be happy when you are not. On the contrary, Bonhoeffer was correct that we should not even concern ourselves with something as mercurial and transitory as our own personal happiness. In fact, when a person’s life is filled with meaning, he will sometimes turn away from pursuing happiness in order to aim at something higher. We see this in Bonhoeffer’s decision not to escape from prison when he had the opportunity, lest this inadvertently endanger members of his own family.[4]

Paradoxically, however, by living lives filled with meaning, especially when that meaning is directed towards serving others, we increase our opportunities for happiness more than if happiness had been our direct goal. Frankl showed this in a manuscript he wrote prior to his imprisonment and which he took with him into the camp. The work, titled The Doctor and the Soul: From Psychotherapy to Logotherapy, argued that joy could never be an end to itself, but arose as a byproduct to a life directed to outward ends. When the manuscript was discarded at the camp, Frankl reconstructed it from memory and published it after being released. Listen to these powerful words from the book:

“…joy can never be an end in itself; in itself, as joy, cannot be purposed as a goal. How well Kierkegaard expressed this in his maxim that the door to happiness opens outward. Anyone who tries to push this door open thereby causes it to close still more. The man who is desperately anxious to be happy thereby cuts off his own path to happiness. Thus in the end all striving for happiness—for the supposed ‘ultimate’ in human life—proves to be in itself impossible.”[5]

Natural vs. Synthetic

Recent laboratory research supports Frankl’s basic thesis that happiness occurs as a byproduct of pursuing ends other than happiness itself. The research even suggests that a life of ease—a life in which everything goes well for us in the external world—can actually block us from having an inner sense of wellbeing.

Much of this research comes from the psychologist Dan Gilbert, who has spent a good portion of his career doing clinical experiments on the ingredients that go into a fulfilled life. In his Ted Talk on Happiness, Gilbert makes a distinction between what he calls “natural happiness” and “synthetic happiness.” Natural happiness is the sort of happiness you receive when you get what you want. For example, you want a new car, your dream job, or a soul-mate, and when you manage to obtain the object of your desires you may feel happy. But what Gilbert calls “synthetic happiness” is the type of happiness you make for yourself when you don’t get what you want, when your needs are not being met and yet your attitude is still one of thankfulness, joy and peace.

The really interesting part of Gilbert’s research is that sometimes it takes deprivation in the realm of natural happiness (i.e., not having one’s needs and desires met) to propel a person to produce “synthetic happiness” (a type of happiness rooted purely in attitude).

I personally don’t like Gilbert’s terminology, as “synthetic happiness” sounds rather artificial, which it is certainly not. However, Gilbert’s basic point coheres with what I saw when studying the victims of the Nazis and Communists. Again and again the prison literature shows that when a person’s external world becomes unusually restricted, it forces a person to realize resources that are available within her own heart (resources a person may not realize she had, if her life had remained easy and without suffering). Often it is great personal tragedy that enables a person to tap into deeper meaning and to realize that what is truly important in life is more lasting and important than what is happening around us.

Gilbert’s research shows that the things inside us that we can control (i.e., things like our attitude, values, and deepest spiritual convictions) are more important than the things in the world that we cannot control (i.e., how other people treat us, what opportunities we have, what is happening in our external environment).

This happened to the Apostle Paul when he was imprisoned by the Romans. Some of the Apostle’s most joyful words are found in his epistle to the Philippians, written during his imprisonment. There is much advice Paul could have given the Philippians, but through the Epistle he keeps coming back to one recurring theme: the importance of attitude. Paul’s concern about attitude culminated in this powerful passage from chapter 4.

“Be anxious for nothing, but in everything by prayer and supplication, with thanksgiving, let your requests be made known to God; and the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will guard your hearts and minds through Christ Jesus. Finally, brethren, whatever things are true, whatever things are noble, whatever things are just, whatever things are pure, whatever things are lovely, whatever things are of good report, if there is any virtue and if there is anything praiseworthy—meditate on these things.” (Philippians 4:6-8)

References

[1] Dietrich Bonhoeffer, cited in Eric Metaxas, Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy : A Righteous Gentile vs. the Third Reich (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2011), 496.

[2] Viktor E Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning (New York, NY: Simon & Schulster, 1959), 55–56.

[3] Ibid., 86 & 88.

[4] Metaxas, Bonhoeffer, 494.

[5] Viktor Emil Frankl, The Doctor and the Soul: From Psychotherapy to Logotherapy (Vintage Books, 1986), 40.