How the Collapse of Modern Individualism is Heralding a New Politics of Community

For years, American politics has overlooked the need for community, treating humans as isolated individuals who can look to the state as the source of all human good.

We saw this conceit on full display with President Obama’s “The Life of Julia” campaign, which walked us through a fictional woman’s life, from birth to death, showing how government-dependence enabled Julia to achieve a near fairy-tale existence without reference to any relationships or community (with the exception of a “community garden” where Julia worked in her retirement). It was a lonely vision in which community was replaced by bureaucracy. Obama’s Julia advertisement gave us a close up view of a paradox that lies at the heart of the modern political project, namely that individualism and authoritarianism cross-fertilize each other in their mutual antagonism to human community.

This individualistic conception of the human being is deeply unsatisfying, for it perpetuates the conceit that we can ignore the inescapable role that non-governmental institutions (i.e., family, church, fraternity associations, neighborhoods, guilds, extended family groups) play in human flourishing.

The role of community, long suppressed in politics, has now returned with a vengeance through anti-individualistic movements on both the left and the right. On the left, the emergence of identity politics repudiates the long-standing tradition of individualism, and associated ideas like free speech and personal autonomy. While offering lip service to personal autonomy, the new race-based tribalism (now given intellectual legitimization in doctrines like CRT) seeks to enforce revisionist virtues based on new theories of race and sexuality. But even while leftist identitarians and LGBTQ radicals are bringing community back to the center of political discourse, the vision of community they offer is one that many find oppressive because of its demand for GroupThink.

Similarly, on the political right, new movements like “national conservatism” and the “post-liberal right,” are gaining momentum in repudiating the values of individualism and its corollary doctrines of personal autonomy, free speech, religious freedom, and limited government. Instead, these movements seek to return to an older model rooted in the centrality of community and voluntary associations. This movement encompasses everything from the academic erudition of Patrick J. Deneen to more authoritarianism proposals for a post-liberal American future.

Whatever else we may think of these movements on both the left and the right, they are exposing the vacuity of atomized individualism, reminding us that humans are inescapably communal creatures. The centrality of community, long suppressed in post-Enlightenment politics, is returning with a vengeance.

Of course, the individual and the community need not be mutually exclusive; on the contrary, it is only through community that we properly flourish as individuals. But individualism has proved inherently antithetical to community ever since it emerged out of the Enlightenment myth that the best way to secure individual autonomy is to produce a value-neutral state that privatizes the good.

John Milbank and Adrian Pabst, working the context of a particularly British Thomistic post-liberalism (yes, such a synthesis does indeed exist), have shown that the Enlightenment privatization of the good has led to a deeply diseased anthropology, a virtue-less politics, and a public order that promotes individualism at the neglect of the human need for community. From their book, The Politics of Virtue: Post-Liberalism and the Human Future:

The whole liberal tradition faces a new kind of crisis because liberalism as a philosophy and an ideology turns out to be contradictory, self-defeating and parasitic on the legacy of Greco-Roman civilization and the Judeo-Christian tradition, which it distorts and hollows out…. Just as liberal thought has redefined human nature as fundamentally individual existence abstracted from social embeddedness, so too liberal practice has replaced the quest for reciprocal recognition and mutual flourishing with the pursuit of wealth,, power and pleasure – leading to economic instability, social disorder and ecological devastation.

The solution, Milbank and Pabst argue, is to reject the political conceits of modern individualism—now on its last legs—and return the community to the center of political discourse and action, thereby attaining “a post-liberal politics of virtue that seeks to fuse greater economic justice with social reciprocity.” Echoing distributists like G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, they urge a model of statecraft that “rejects the double liberal impersonalism of commercial contracts between strangers and individual entitlement in relation to the bureaucratic machine.”

But not everyone agrees that Enlightenment individualism is on its last legs, nor that the present ailments have anything to do with the unsustainability of modern individualism. Last month author George Will published an opinion piece in the Washington Post in which he decried the erosion of individualism in America’s emerging political movements. “Modernity’s greatest achievement,” he wrote, “was the invention of the individual.” His article featured a picture of a lonely woman walking across a bridge, eerily reminiscent of the Life of Julia.

Mr. Will’s article, titled “National conservatives and racial identitarians have a common enemy: Individualism,” drew on the twentieth-century British philosopher, Michael Oakeshott, who suggested that the legacy of modern individualism was (in Will’s words) to create “a zone of personal sovereignty independent of communal arrangements.” Will argues that Oakeshott got this correct, since the purpose of government is “not the pursuit of the good life” but “the pursuit of happiness as the individual defines it.”

The vision Mr. Will articulates is a familiar one, as it has been central to the classical liberalism of the modern age. Classical liberalism asserted that the state can be value neutral, and exists not to secure the good but to privatize it; to create a zone of maximal autonomy in which citizens can go about their business pursuing their own private goods, the chief of which is the pursuit of happiness.

What men like George Will—among the last vanguards of America’s collapsing liberal order—fail to appreciate is that this vision is inherently unsustainable and must eventually collapse under its own weight. Why? Because even supposedly private ends like individualism and personal autonomy cannot exist without some level of community enforcement, a fact that has been on full display in the battle over, so called, “transgender rights.” As Sohrab Ahmari pointed out in a much-discussed 2019 article for First Things, the logic of maximal autonomy requires society to give as wide a berth as possible to anyone wishing to redefine what is good, true, and beautiful, even if that means creating a society that is deeply unsatisfying and unfree for others.

What we are discovering is that humans are essentially communal creatures, while communities are, by their very nature, oriented towards a certain vision of human flourishing, which is to say, some conception of The Good. Failure to recognize this will invite a diseased public order in which the teleological orientation of community emerges in toxic and unexpected ways, and in which disputes about virtue play out in a range of proxy conflicts that fail to acknowledge that what is really at state is really competing notions of The Good.

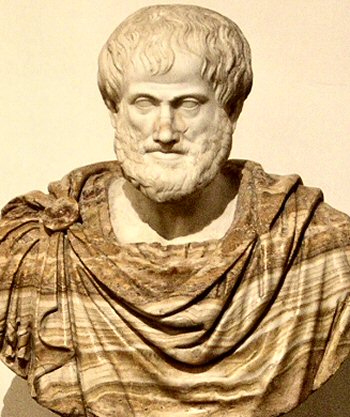

Once we understand that there can be no teleology-free politics of the sort envisioned by Oakeshott and Mr. Will, and once we realize that Plato and Aristotle were actually correct in understanding that the purpose of politics is to produce communal virtues, then we can have a robust discussion about what type of public virtue we should be aiming for and why. Whether we agree with the post-liberal movements on the left or the right, we can at least be thankful that they are returning our public discourse to these fundamental questions, and reasserting the primacy of community.

Further Reading