Struggle is good. It is through struggle that you and I become the sort of people we are, and it is through struggle that we form the attitudes and dispositions that eventually come to feel natural to us. It is also through struggle that we determine what we find enjoyable, attractive, and beautiful.

For example, if you think of the joy a married couple feels when celebrating their 40th wedding anniversary, few would doubt that such joy is the product of years of sacrifice, hard work, and maybe even hardship. Indeed, struggle is often a necessary prelude for joy. Ultimately, the reward of properly directed struggle is to become a certain sort of person, one who can delight in what is good, true, and beautiful.

It is easy to misunderstand the type of reward that comes at the end of struggle, since modern economic systems are built around reward incentives that usually have no organic connection to our labor. When I used to clean toilets for a living, the rewards that were intrinsic to my work (for example, the satisfaction of seeing a clean toilet) were not sufficient to motivate me to keep showing up to work each night. I showed up because of the paycheck, which was a reward entirely extrinsic from the work itself.

In the modern world, if we want to find examples of rewards that are organically connected to our work, we will be more likely to find them in the field of education and morality. I have a friend who achieves great joy by writing poems with alliterative meter in the style of Beowulf, yet his joy is only possible because he spent years studying Anglo-Saxon literature and language. Similarly, the enjoyment a man might derive from having a relationship with a modest, virtuous woman is organically related to the work of becoming virtuous himself. One who has not worked to appreciate good literature may puzzle why my friend would derive so much enjoyment from imitating Anglo-Saxon verse, just as a man who has not worked to cultivate virtue may find it hard to understand why another would enjoy having a relationship with a modest, virtuous woman. Yet it is through struggle, including the struggle of habit-forming behaviors that may initially feel contrived, that we arrive at our deepest dispositions that determine which behaviors eventually come to feel enjoyable to us.

The training of our desires and affections is, of course, the telos of education as classically conceived. Before education was taken over by relativism, educators believed it was their duty to form students according to what is really good, true, and beautiful. As C.S. Lewis put it in The Abolition of Man,

The little human animal will not at first have the right responses. It must be trained to feel pleasure, liking, disgust, and hatred at those things which really are pleasant, likeable, disgusting, and hateful…. From his earliest years [he] would give delighted praise to beauty, receiving it into his soul and being nourished by it, so that he becomes a man of gentle heart. All this before he is of an age to reason; so that when Reason at length comes to him, then, bred as he has been, he will hold out his hands in welcome and recognize her because of the affinity he bears to her.

As modern men and women, it seems presumptuous that educators would aspire to train attitudes and preferences. We tend to assume that our preferences, and the emotions with which they are correlated, just happen to us like getting a cold, and are thus off limits to what can be trained through effort, behavior, and struggle. Thus, the assumption is that if we have to work at feeling a certain way, or if we have been influenced to feel a certain way by struggle, then the resulting feelings are somehow less authentic, less true to ourselves compared to dispositions that arise involuntarily and without effort. Accordingly, we may think that dispositions arising after a period of struggle, and after a period of habit-forming behaviors, are somehow artificial and fake. Culture and advertising reinforce this message, implying that we are at our most authentic when we are being spontaneous.

But this is simply not accurate to how the world works, as we saw from the previous examples. The joy a married couple feels when celebrating their 40th anniversary is no less genuine merely because their relationship required enormous effort and work; in fact, quite the contrary. As any healthy married couple will tell you, for a relationship to thrive, one must continually engage in practices that cultivate closeness even when you don’t feel like it. For example, a man doesn’t only kiss his wife when he feels attracted to her; he also kisses his wife in order to cultivate feelings of attraction. This is similar to how the Christian will kneel to say prayers of repentance not merely when she feels penitent, but also to cultivate appropriate penitence.

How The Struggle-Free Life Became Attractive

In our culture of comfort and self-gratification, the concept of training our affections through struggle has fallen on hard times. In large part this has occurred, not because we have rationally deduced that struggle is no longer good for us (on the contrary, all the latest science attests to the value of struggle), but because our hearts and imagination have been stirred by the counterfeit beauty of comfort, ease, and the frictionless life. Our music, movies, and media present the path of least resistance as beautiful. For example, country music, once a genre where you could be sure to get inspired by the glory of hardship and struggle, has begun pandering to weakness by romanticizing comfort, convenience, and passivity.

On one level this is a worldview problem, related to many of the isms of modernity, including individualism, egotism, utilitarianism, and secular humanism. Yet the fundamental reason we fall for the allure of a struggle-free life is not primarily intellectual but because of corruption at the level of imagination. Once the imagination has become corrupted, it is easy to perceive things that are ugly, false, and dehumanizing as if they are ennobling, beautiful, and glorious.

That is why the new country music is so subversive. Through the use of powerful imagery in songs and music videos, the recurring message, “Don’t struggle, just do what comes naturally,” is contextualized in a way that makes this message seem fun and romantic. Similarly, many contemporary movies—one thinks of the 2010 hit Eat Pray Love—promote a life of utter selfishness as truly therapeutic and self-fulfilling.

There is an important spiritual truth to learn here, which is that the cosmic battle between the seed of the woman and the seed of the serpent often plays out in the domain of imagination. As I explained in Rediscovering the Goodness of Creation:

Satan is quite satisfied to let us go about our business as Christians—to attend church, to lobby our politicians, to have Bible studies and catechism classes—as long as he can control our imaginations. Once a child’s imagination has become corrupted, then all the church services, catechism classes, family worship, and good education in the world will accomplish little.

Imaginative Apologetics

The above observation about the devil’s tactics might lead us to disparage the imagination as if it is wholly bad, an instrument of the devil. Yet in the battle for our hearts and minds, the imagination is also a key instrument the Holy Spirit uses to reorder our affections. This is something that C.S. Lewis understood so well. In his work as a Christian apologist, Lewis used fiction as a vehicle for reordering the imagination.

Christian apologists today must defend the value of struggle, and while we can do this by appealing to the latest discoveries of social science, it is perhaps more important to use art and storytelling to reframe struggle. Art and storytelling can show, on a deep precognitive level, that struggle is beautiful, and that the type of frictionless life promoted by contemporary music and film is ugly, empty, and not even very romantic.

Currently, story-telling through movies tends to do the opposite. For example, movies like the 2010 hit Eat Pray Love, promote a life of utter selfishness as truly therapeutic and fulfilling. More recently, the movie Barbie culminates, not in the main character maturing from girlhood to womanhood, but in finding order in the self-centered independence of perpetual immaturity (see Annie Crawford’s article “Existential Barbie.”) However, many contemporary novels and movies do inspire us with the glory of appropriate struggle and even hardship. Attention to these novels and movies offers an opportunity to push back against the cult of self-gratification. That said, in the remainder of this article, I won’t be looking at contemporary film and literature specifically, but my two favorite movies from the Golden Age of Hollywood. These movies are not only great stories and beautiful art, but do a particularly good job portraying that glories of struggle.

High Noon: The Glory of Struggle

The first of the two movies I’d like to discuss is the 1952 film High Noon, starring Gary Cooper and Grace Kelly. The film opens on the morning of Marshal Will Kane’s wedding to Amy Fowler, who is a Quaker. Because a new marshal will be arriving in town the next day, and because of the pacifist convictions of his bride, Kane hands in his badge and gun, planning to start a new life as a shop owner. But as the couple is preparing to leave town, word reaches Kane that the vicious outlaw, Frank Miller, is on his way to town on the noon train, and that Miller’s old gang have congregated at the station to wait for him.

Miller had been sent to prison some years earlier when Kane was cleaning up the town. But while serving time in prison, Miller vowed to avenge himself on Kane. Knowing that Miller’s quarrel is with Kane alone, and that a new marshal will be arriving the next day, the townspeople hustle the new bride and groom out of town. But a sense of duty calls Kane back to defend himself and the town against the coming threat. He expects his friends in the town to stand by him and help, yet one by one they desert him until Kane is left to face the entire gang all by himself.

Cooper does an amazing job playing Kane. He has none of the bravado or fearlessness of someone like Bruce Willis in the Die Hard movies, or Tom Cruise in the Mission Impossible remakes. Unlike the macho man trope, where a hero never shows the fear and vulnerability that is a precondition to courage, Marshal Kane is genuinely scared. Yet this very fear becomes the birthplace of authentic courage.

Whereas in contemporary tough-guy movies it is usually the outcome that is rewarding, in High Noon it is the struggle itself that we find rewarding, exhilarating, and glorious.

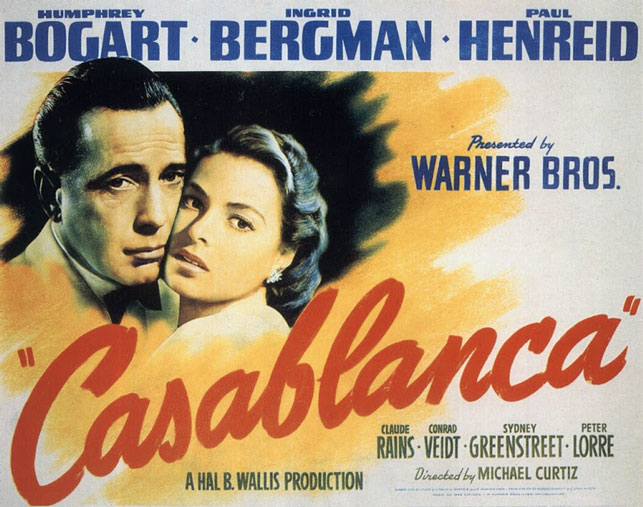

Casablanca: The Beauty of Self-Sacrifice

Another film that offers a positive valuation on struggle is the 1942 movie Casablanca. Starring Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman, it tells the story of American expatriate Rick Blaine, who operates an American style nightclub in the North African city of Casablanca during WWII. Amid the political tensions and intrigues of the Vichy-controlled city, Rick walks a fine line of neutrality, cynically declaring that he cares for no one except himself. Yet through flashbacks, we learn that Rick once did care for someone, a woman named Ilsa Lund that he met in Paris before its occupation by the Nazis. Rick and Ilsa had a whirlwind romance until, on the eve of their escape from impending occupation, Ilsa mysteriously disappeared, leaving a note declaring that she was finished with the relationship. Confused and heart-broken, Rick became transformed into the selfish, cynical nightclub owner we find in Casablanca.

Rick’s life becomes disrupted when Czechoslovakian resistance leader, Victor Laszlo, enters Rick’s cafe with his wife, who is none other than Rick’s former lover, Ilsa. Assuming that Ilsa ditched him for Laszlo, Rick refuses to help the pair escape to the west even though it lies within his power to do so. But as Ilsa and Rick have the opportunity to interact, their old love is rekindled, and Ilsa explains what really happened when she mysteriously abandoned him in Paris. When she had fallen in love with Rick, she had believed her husband, Laszlo, was dead, yet she could say nothing about him to Rick since her role in the resistance had to remain secret. However, on the eve of her planned departure with Rick, Ilsa received word that Laszlo was alive and in hiding waiting for her. Instead of escaping with Rick, Ilsa returns to her husband.

As Rick learns the true context of Isla’s earlier departure, and as the pair continues to interact, Rick and Ilsa’s love is rekindled, until she declares she cannot leave him again, and they make plans to escape to freedom in the West. It is easy to root for the success of their relationship because Ilsa shares a bond with Rick far deeper than anything she feels toward her husband, despite the fact that Laszlo is a good man. Rick risks his life to organize a daring escape, yet at the last minute it becomes clear that his plan is for Ilsa to escape with her lawful husband, while Rick will stay behind to face the consequences.

One of the reasons I think Casablanca resonates with audiences throughout the decades is because it shows that the struggle to live sacrificially is ultimately more exciting and romantic than the “follow your heart” trope in so much contemporary film. As we watch Humphrey Bogart transformed from a self-serving cynic to a sacrificial hero, something deep within us soars. We come away from watching a film like Casablanca with a fresh enthusiasm to embrace our own struggles, and to throw ourselves fully into the life of virtue.

Timely and Timeless

High Noon and Casablanca show that art and storytelling can be a powerful tool in retraining our affections. Even though these movies do not have explicit Christian content, they offer a type of imaginative apologetics by portraying virtue as lovely, and showing how beautiful it is to perform one’s duty when faced with pressure to follow the path of least resistance. During a cultural moment when so much art and music disorders our affections by pandering to a life of ease and comfort, these movies from the Golden Age of Hollywood offer a timely and timeless antidote.

The material for this post originally appeared in my column at Salvo Magazine and is reprinted with permission of the author (me).