Those who have been following my work on Gnosticism, have probably grown used to me referring to Plato in a disparaging way. He is routinely touted as the great proto-Gnostic, the guru of all who suffer from body-hatred. I was not alone in this negative view of the great Athenian. Much of the Christian literature that laments the Gnostic tendencies in the contemporary church tends to use the adjectives “Gnostic” and “Platonic” interchangeably (Randy Alcorn and N.T. Wright are two notable examples).

When I was thirty-five and began pursuing graduate studies at King’s College London, I continued to hold this negative perspective on Plato’s legacy. I had a friend named Bret who occasionally approached me to explain that there was another side of Plato that I needed to consider—a side which actually offered a positive valuation to the material world—but I was obdurate: Plato was a proto-Gnostic. “Just read the Phaedo,” I replied. “and you’ll see that he was a systemic body-hater.”

But last year I began exploring Plato more deeply. I found that a correct understanding of Plato’s philosophy, rooted in his historical context, can actually support creation’s goodness. I discussed some of this transition in episode 15 of my podcast. As I explained there, Plato helped me begin to see that it is precisely because the good, true, and beautiful things of this material world reflect realities beyond this world (or, if you prefer more Biblical language, realities beyond the present stage of redemption history) that material creation can be given a high spiritual valuation, even while that valuation must be qualified in important ways.

In the present series of articles (this post, and two to follow), I want to explore Plato’s complex relationship with the material body, and the ramifications this had for Christian Neoplatonism. I will be looking at how Plato’s insights into the metaphysics of goodness, truth, beauty, and love can be leveraged spiritually, in the context of Christian theology. In this process, we will explore how the early Christians appropriated Plato’s doctrine of participation, and how the doctrine of participation brought together both Hebrew and Roman strains of influence. Various thinkers will guide us in this journey, including St. Augustine of Hippo, who used Neoplatonism as a powerful weapon for asserting the goodness of creation against the world-denying heretics of his day. A recurring question throughout this series will be how the beauty of this world (even in its fleshly forms) relates to the beauty of the Almighty.

Let us begin by looking at Plato’s relationship with Gnosticism.

Plato the “Gnostic”?

It is a curious, but highly significant, fact that the Nag Hammadi library of Gnostic texts contained an altered version of Plato’s Republic – altered in order to align with then-current Gnostic theories. The inclusion in this collection of a work by Plato is fitting since he has been associated with the same negative view of the material creation that we find in The Gospel of Thomas and many of the other Gnostic texts within the Nag Hammadi collection. In fact, it seems to me—although I have not proved this hypothesis—that the second most common use of the adjective “Platonic” is in reference to disparaging the physicality of our existence.[i]

Although Plato lived hundreds of years before Gnosticism, it cannot be denied that his philosophy was very influential for the Gnostics. The Gnostic teacher, Valentinus (100 –160), claimed to draw on Plato and relied upon the second of thirteen epistles often attributed to the Athenian philosopher.[ii]

By the third century, Neoplatonism was so popular among the Gnostics that the great Neoplatonic philosopher, Plotinus (c. 204/5–270), had to write a treatise clarifying that Gnosticism was incompatible with the principles of his philosophy. Yet Plotinus’s approach to the body still relegated it to one of the lower levels on his great chain of being. Man, he taught, is suspended between mind and matter, and is only perfected through ascending upward through mind to reach mystical experience and the higher levels of being, rather than descending to the material world at the lowest level of the chain.

It is not hard to see why Plato attracted Gnostics like dead meat attracts flies. He referred to the body as a prison, as reflected in his famous dictum “soma sema” (“a body, a tomb”). His vision of a higher world of forms—the true realities of which everything else is but a shadows—fit nicely with the Gnostic idea that the purpose of existence is to escape from this lower world of matter and differentiation. Unlike Plato’s down-to-earth student Aristotle, who got his hands dirty studying plants and animals, Plato’s pie-in-the-sky philosophy offered very little incentive for valuing the passing realities of our ephemeral world. Or, at least, that is one rather simplistic stereotype of Plato’s philosophical contributions.

Given this view of Plato—which certainly has prima facie textual support in a number of his important dialogues—it is more than a little ironic that by the fourth century, Christians were using Neoplatonism as one of their chief weapons for affirming the goodness of the created world. Indeed, Neoplatonism offered thinkers like St. Augustine of Hippo (354–430) a resource for defending the high value Scripture placed on the material world. Should this be dismissed as a quirk of history, or is it something that can challenge us to rethink common assumptions about Plato? Was Plato’s philosophy the greatest ally of implicit Gnosticism, or its greatest challenge? This problem can be resolved by placing Plato back in his historical context—a context that evolved throughout his career.

Plato and the Search for True Being

Plato lived at a time when the city-state of Athens was undergoing great political and social turmoil. His teacher, Socrates, had been executed in 399 BC as part of a political backlash as the Athenian government tried to reassert stability following their defeat in the Peloponnesian War. Plato also sought to find stability, but for him it lay in the realm of True Being beyond the present world of change, corruption, mutability, and materiality. Plato came to associate True Being with the ultimate essences, or forms, of values like Beauty, Virtue, Goodness, Justice, and so forth. These perfect forms are not found in this world, although the intellect can deduce their existence through reason.

In one of his early dialogues, the Phaedo, Plato used the example of equality to help explain the relationship between the realm of the Forms and the everyday world of sense perception. In our world we experience things that are alike and unlike. For example, we might see two lines of the same length and then call them equal. But the perfect idea of equality—what some translators of Plato have called its “abstract essence”—is prior to these particular instances.

What is true for equality is also true for essences like Beauty, Wisdom, and Goodness: these forms exist in an immaterial world beyond the physical world. Let’s look closer at the Phaedo where Plato developed these ideas.

Plato the Dualist

The Phaedo is set during the last day of Socrates’ life, just before he drank poison to fulfill his death sentence. Seeking to comfort his mourning disciples, Plato’s Socrates describes the soul as kin to the unchanging, immaterial forms that exist in the higher world beyond this life. Accordingly, death is good because it releases the soul from the chains of physicality to be united with True Being in the realm beyond.[iii] From there, Plato went on to argue that philosophy invites us to dwell on the higher realities beyond the material world, in preparation for death when the soul leaves the prison-house of the body.

Plato wanted his readers to understand that there is a dualism between body and soul that culminates in their ultimate separation at death. In contrast to the Christian tradition, which would come to see the separation of body and soul at death as an aberration and a sign of spiritual disease, Plato saw this separation as normative, and even the special delight of philosophers. “And the true philosophers, and they only, study and are eager to release the soul. Is not the separation and release of the soul from the body their especial study?”[iv] Plato made the same point elsewhere by declaring that the philosopher “has as little as possible to do with the body” and “dishonors the body” and “runs away from the body,”[v] and that philosophers “have been always enemies of the body, and wanting to have the soul alone…”[vi]

For Plato, it was not just the body that is the enemy of true philosophy, but the entire physical world that we perceive through our senses. This is because the philosopher is one who approaches absolute Beauty, Goodness, Justice, and Truth through pure reflection unmixed with empirical observation.[vii]

The Phaedo offered a spiritual psychology that is dualistic, for the human person is divided between the pure soul (associated with the intellect), and the impure soul (associated with attachment to bodily things).[viii] The philosopher anticipates the final freedom when the soul “takes leave of the body, and has as little as possible to do with it, when she has no bodily sense or desire, but is aspiring after true being…”[ix]

The Phaedo reflects theories that Plato likely promoted in the school he founded, known as the Academy. Significantly, this school had the following inscription at its entrance: “Let no one ignorant of geometry enter here.” This inscription is important, because it reflected Plato’s concern to construct philosophy on the model of mathematics. If a mathematician wants to know about the true nature of a triangle, he does not reflect on particular triangles in the world; rather, he contemplates the true form of a perfect triangle as it exists in the mind’s eye. When we describe the properties of a triangle (for example, that the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides), we are describing truths that apply to the perfect eternal idea of a triangle, not truths that are limited to particular triangles that are never absolutely perfect and remain only particular temporal instances of the triangular form. Triangles within the world are at best distortions or shadows of the perfect eternal form of a triangle. Similarly, to find true justice, true goodness, or true beauty, the philosopher must look away from the present world to the unchanging essences of things that can only be accessed through intellectual vision.

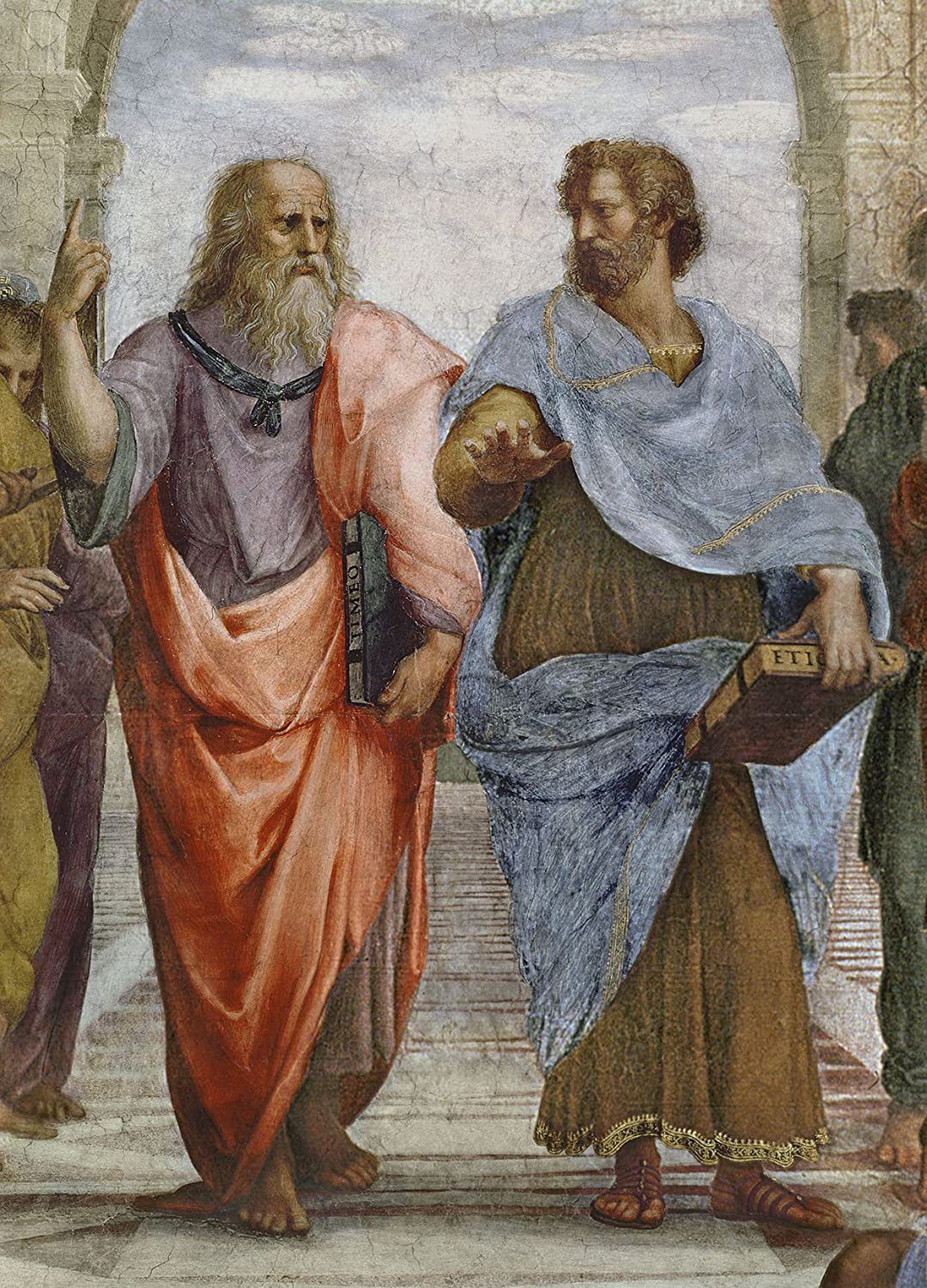

Enter Aristotle

Things became more complex for Plato sometime after he accepted an 18-year-old student named Aristotle into his school. Aristotle, who joined the Academy in 367 BC, had (or came to have) a very different outlook than his master Plato. For Aristotle, the model for philosophy was not mathematics but biology. His father had been a physician, and from a young age Aristotle learned the value of careful observation. Aristotle believed that it is only through observing particular things in this world that we discover the true form of things. Whereas Plato might have spent time reflecting on the unchanging essence of horse-ness, Aristotle would get his hands dirty dissecting an actual horse. Aristotle would come to write books on metaphysics and logic, but he also wrote works on the parts of animals and plants, including a defense of dissection. He was as much a scientist as a philosopher, though the strict distinction between those disciplines did not yet exist.

Plato’s Tripartite Spiritual Psychology

We get a glimpse of Plato’s evolving thought in some of the dialogues he wrote in his latter life, or what historians call his “middle period.” While Plato does not go so far as Aristotle in asserting that the eternal forms of things are embodied in matter, he does begin suggesting that True Being can be reflected in material particulars. For example, in his great work on political theory, the Republic, Plato argued that a just society can reflect, or be an image of, the eternal truth about Justice.

Plato’s spiritual psychology also gradually became more complex, allowing for human beings to reflect (albeit imperfectly) the ultimate forms of things. No longer content with a simple mind-body dualism, Plato began arguing that the soul has three parts. He outlines this tripartite division in the Republic, where he suggested that the three parts of the soul parallel the three classes of people in a just society.

The highest part of the soul is the intellect, through which we perceive eternal forms like Justice, Virtue, Goodness, Wisdom, etc. Below this is the middle part—let’s say the chest—that can choose to listen to reason, and thus to bring Justice, Virtue, Goodness, etc., down to earth. This is the emotional or “spirited” part of man, like a spirited horse who fights its bad impulses to submit to its master. The third and lowest part of the soul is represented by the gut, the part of man concerned with eating, reproducing, lusting, and the bodily appetites.

Through this more complex spiritual psychology, Plato allowed for man to have great potential even while in the body, since it emphasized the possibility of mastering our baser instincts. We can govern our bodily desires and put them in the service of higher purposes as we cultivate the harmony of a virtuous soul. As the emotional and spirited part of man turns away from the appetitive part, and chooses to submit to the rational part, then man can fulfill his function as a good citizen, a good soldier, a good father, and so forth. In this way, the physical human being can partially reflect true Justice, Truth, Virtue, Wisdom, Beauty, Goodness, etc., in the same way that a just society can image the eternal forms of things.

The Ascent of Beauty and Love

In his later career, Plato remained focused on transcendent realities, yet under the presumed influence of Aristotle he began integrating the philosophical quest into all aspects of individual and civic life, rather than simply pointing away from this world. He stopped being concerned merely with escaping from the body and society, but instead he took an interest in ruling the body and society through the moderation of virtue. Even in the famous allegory of the cave in The Republic, the realm of shadows is seen as reflecting, rather than simply obscuring, the true reality that our souls are seeking. The forms of this world—imperfect shadows of ultimate Goodness, Truth, Beauty, etc.—can beguile us if we mistake these shadows for the final reality, or they can become portals through which the highest part of the soul ascends into the sunlight of ultimate truth.

This path of ascent from the shadows to the realities is made explicit in two key texts from Plato’s later writings, the Phaedrus and the Symposium. These dialogues, which should be considered as a pair, show that Plato had become intrigued by questions of love. What happens when we fall in love? Why do we feel what we feel when we see a beautiful human body? Plato’s answer is that falling in love reminds us of an eternal beauty that our soul remembers from before birth. The beauty of another person’s body, and the strong desire we feel to unite ourselves with that beauty, is an echo of the soul’s remembrance of divine beauty, betokening an innate desire to be united with the Ultimate Beauty.

This philosophy of love was partially articulated in a highly significant passage in the Phaedrus, where Plato is exploring the beauty that lies behind our experience of erotic love. At one point in the dialogue, Plato has Socrates make the following observation:

“But of beauty, I repeat again that we saw her there shining in company with the celestial forms; and coming to earth we find her here too, shining in clearness through the clearest aperture of sense.”[xii]

Here Plato is referring to the heavenly realm of forms, where the soul is nourished by perfect Goodness, Truth, and Beauty. But unlike his earlier work, the Phaedo, he now allows that the beautiful things of this world—things that we perceive through the senses—have value in pointing us to the ultimate Beauty in which they participate and from which earthly particulars derive their coherence. Through sense perception we can perceive dim reflections of true beauty even during this life of finitude and mortality. As we perceive beauty in this world, we have two choices: either we can surrender to concupiscence and give way to carnal appetites (what St. Paul would later refer to as “the lusts of the flesh”), or we can respond to beauty as an icon of transcendent, absolute Beauty. If we take the second course, then the beautiful things of this world become portals, carrying us beyond this world to the true Beauty of which all particular instances are but an imitation. Thus, Plato continues:

“Now he who has not been lately initiated or who has become corrupted, is not easily carried out of this world to the sight of absolute beauty in the other; he looks only at that which has the name of beauty in this world, and instead of being awed at the sight of her, like a brutish beast he rushes on to enjoy and beget; he takes wantonness to his bosom, and is not afraid or ashamed of pursuing pleasure in violation of nature. But he whose initiation is recent, and who has been a spectator of many glories in the other world, is amazed when he sees anyone having a godlike face or form, which is the expression or imitation of divine beauty…”[xiii]

Notice the role that physical sight now plays for Plato. In this more mature philosophy, Plato allows that physical vision of beautiful things can aid the intellectual vision of eternal forms, or what he calls “divine beauty.” Seeing a beautiful person—what Plato calls “a godlike face or form”—carries us beyond this world, since this beauty is “the expression or imitation of divine beauty.” Elsewhere in the Phaedrus he declares that when the lover is able to “behold the flashing beauty of the beloved” then “his memory is carried to the true beauty.”[xiv] We might say that Plato’s thought has been able to “redeem” the material world by seeing the good and beautiful things of earth as portals through which the soul can ascend to divine goodness and beauty. In this development Plato not only reflected the likely influence of his student Aristotle, but also the method of constant questioning and truth-seeking that he inherited from his teacher Socrates. Plato was not content to remain static but followed Socrates’ example of constantly searching after deeper wisdom.

Plato’s deeper wisdom reached a pinnacle in the Symposium, widely considered to be one of the greatest works of literature ever produced.[xv] Whereas the main topic of the Phaedrus was rhetoric and only touched on the philosophy of love and beauty in passing, the Symposium is entirely devoted to these themes. This dialogue is set in a drinking party, where the characters take turns giving speeches to explore the nature of love. When it is Socrates’ turn to speak, he recalls having sought out a prophetess from the Peloponnesian town of Mantineia. The prophetesses, a wise woman named Diotima, initiated the philosopher into the mysteries of the deep spiritual connection between desire, love, beauty, and goodness. As Socrates continues recounting what he learned from the prophetess, he progressed from the lesser mysteries of love to the higher mysteries, in much the same way that initiates into the Eleusinian Mysteries would progress from the lesser to the greater mysteries of the cult. The greatest and most hidden mysteries of love that Socrates learned from Diotima, which she maintained could only be grasped with the right spirit, is that the beautiful things of this world act as a ladder by which we ascend to heavenly realities.

The argument that Socrates received from the prophetess proceeded something like this. A well-educated youth will be taught to recognize and love beauty. His journey begins with an attachment to one beautiful thing,[xvi] and through that thing to beautiful ideas. In time, the student is exposed to more beautiful things and ideas, and he begins to see that the particular beauty in these various forms is related by the common quality they all share. (To put this in contemporary terms, we might say that a child who is educated to enjoy beauty in the music of Bach and Schubert, the poetry of Coleridge and Longfellow, and the painting of Michelangelo and Rembrandt, begins to recognize that there is a common quality of beauty that all these works have in common.) The student will thus abandon a fixation on simply one beautiful form but will come to love all beautiful things, and to recognize and love the quality they share in common.

Over time, the student will transcend to higher forms of beauty and come “to consider that the beauty of the mind is more honorable than the beauty of the outward form.”[xvii] One way I like to explain this stage in Plato’s argument—that is, the progression from the realm of the senses (“outward forms”) to the realm of the mind or soul—is by observing what happens when we are attracted to a beautiful person. Initially a man may be attracted to a woman for her physical charms, but if she is virtuous then the man can ascend to love for her inner qualities such as her temperance, modesty, kindness, humility, intelligence, and so forth. But if the man is shallow, unsophisticated, or spiritually unformed, then he may never rise above a purely physical attraction. To give an example from the female point of view, a woman may be attracted to a man—let’s say, someone she sees in a Western—because he is handsome, tough, skilled, wealthy, or has a winning personality. But if she is a woman of inner resources, then she will ascend to a love for the man’s inner resources: let’s say his courage, self-control, nobility, truth-seeking, sensitivity, and intelligence. If she is a woman of virtue, then instead of fantasizing about having a husband like the man in the Western, the woman will think, “I want to be courageous, noble, sensitive, and virtuous like that man,” and she will work to cultivate those qualities in her own life. If she is already married, she will love and encourage these qualities as they are manifested in her husband, and treasure these above purely external features.

But love for the soul’s inner qualities is still not the final stage. The Mantineian prophetess told Socrates that after the ascent from love of physical beauty to love of soul, the philosopher ascends to love of city, and the beauty of just laws and institutions. From there we ascend to love of the sciences, until finally we ascend to the highest vision of all, which is to love and long for Divine Beauty. The argument concludes with these words, which are a fitting climax not simply to the central argument of the Symposium, but also to Plato’s lifelong philosophical quest for True Being:

“’He who under the influence of true love rising upward from these begins to see that beauty is not far from the end. And the true order of going or being led by another to the things of love, is to use the beauties of earth as steps along which he mounts upwards for the sake of that other beauty, going from one to two, and from two to all fair forms, and from fair forms to fair actions, and from fair actions to fair notions, until from fair notions he arrives at the notion of absolute beauty, and at last knows what the essence of beauty is. This, my dear Socrates,’ said the stranger of Mantineia, ‘is that life above all others which man should live, in the contemplation of beauty absolute; a beauty which if you once beheld, you would see not to be after the measure of gold… But what if man had eyes to see the true beauty—the divine beauty, I mean, pure and clear and unalloyed, not clogged with the pollutions of mortality, and all the colors and vanities of human life—thither looking, and holding converse with the true beauty divine and simple, and bringing into being and educating true creations of virtue and not idols only? Do you not see that in that communion only, beholding beauty with the eye of the mind, he will be enabled to bring forth, not images of beauty, but realities; for he has hold not of an image but of a reality, and bringing forth and educating true virtue to become the friend of God…'”[xviii]

Here Plato presents a path of ascent in which each rung of the ladder is organically related to the preceding steps. It is through our attraction to beautiful particulars that we form a conception of beauty in general, just as it is through our love for beautiful bodies that we ascend to the love of beautiful minds, and ultimately to love for Divine Beauty. All these levels of beauty and love are genuinely good, and not merely in an instrumental sense. Whereas Plato once saw the human body as evil, he now sees it as genuinely good, although not the highest good. We can stop on the lower rungs of the ladder, or we can allow the genuine beauty in this world to draw our souls into a longing for ultimate Beauty.

The true philosopher will not remain at the lower rungs of the ladder, but neither will he discard the genuine value of the things he encounters in the lower stages of ascent. Rather, one who has grasped Divine Beauty can still feel attracted to genuinely beautiful things of this world, but those beauties are taken as a reflection of, and a participation in, the higher Beauty. Through love and desire for immanent good and beautiful things, the soul is prepared to love and desire transcendent goodness and beauty. On the other hand, the student who is never trained to experience wonder in the presence of earthly beauty will be ill-equipped to ascend to the transcendent Beauty in which the soul finds its final resting place.

Within Plato’s mature metaphysical reflections, beautiful things of creation, including human bodies, are given a real value and dignity via their participation in the higher realities.[xix] Accordingly, the vision of divine beauty illumines and dignifies all instances of imperfect beauty, as the immanent is transfigured by the transcendent.

In the next article in this series, we will explore the fascinating process whereby Plato’s philosophy was picked up by early Christians to combat Gnosticism. Before proceeding, however, it will be helpful to pause and review.

- Plato’s philosophy has been a favorite for Gnostics of all stripes.

- Plato’s early philosophy did disparage the physical world, in addition to offering a sharp mind-body dualism.

- In Plato’s later life, he began taking an interest in how earthly goodness, piety, beauty, justice, truth, and so forth, reflects and participates in the realm of True Being.

- Through love for immanent good and beautiful things, the soul is prepared to love the transcendent divine goodness and beauty in which the soul finds its true home.

Needless to say, when Plato spoke of divine goodness and beauty, he was not talking about anything resembling the Christian God. After all, Plato was writing hundreds of years before the coming of Christ. Yet Christian theologians were able to appropriate Plato’s philosophy, in addition to building upon the sophisticated intellectual legacy of third-century Neoplatonism. In the next two articles we will consider ways that Christian theologians appropriated Plato’s philosophy, particularly his doctrine of participation, and how they used that in their arsenal of resources against those who were denigrating the material world.

Further Reading

- Plato’s Cave, Education, and the Desire for God

- The Robin & Boom Show #15 – Everything Plato, with Dr. Phillip Cary

- Confessions of a Recovering Gnostic

Notes

[i] The first most common use of the term is to connote a certain type of unconsummated love, which Plato may well have found puzzling.

[ii] Paul Kalligas, “Plotinus against the Gnostics,” Hermathena, no. 169 (2000): 116.

[iii] “What is purification but the separation of the soul from the body, as I was saying before; the habit of the soul gathering and collecting herself into herself, out of all the courses of the body; the dwelling in her own place alone, as in another life, so also in this, as far as she can;—the release of the soul from the chains of the body?” Plato, The Dialogues of Plato (New York: Bigelow, Brown), 199

[iv] Plato, 199.

[v] Plato, 196.

[vi] Plato, 199.

[vii] “And he attains to the knowledge of them in their highest purity who goes to each of them with the mind alone, not allowing when in the act of thought the intrusion or introduction of sight or any other sense in the company of reason…he has got rid, as far as he can, of eyes and ears and of the whole body, which he conceives of only as a disturbing element, hindering the soul from the acquisition of knowledge when in company with her.” Plato, 197.

[viii] The body-soul dualism may seem self-evident to us, but that is because of Plato’s pervasive influence. Both Homer and the Old Testament divide the human person into numerous parts (heart, gut, bowels, spirit/breath, kidneys, liver) that overlapped both physical and non-physical functions.

[ix] Plato, The Dialogues of Plato, 196.

[x] Phillip Cary, Outward Signs: The Powerlessness of External Things in Augustine’s Thought, 1 edition (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

[xi] Not all scholars will agree with my treatment of Aristotle’s influence on Plato. For a survey of competing perspectives on Plato and Aristotle’s relationship, see Christopher Shields, “Plato and Aristotle in The Academy,” in Gail Fine, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Plato (Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 504–5.

[xii] Plato, The Dialogues of Plato, 409.

[xiii] Plato, 409–10.

[xiv] Plato, 414.

[xv] The nineteenth century theologian and classical scholar Benjamin Jowett declared, “Of all the works of Plato, the Symposium is the most perfect in form, and may be truly thought to contain more than any commentator has ever dreamed of.” Benjamin Jowett, Introduction to the Symposium, in Plato, 275 C.S. Lewis went even further, remarking that no one should be allowed to die without first reading the dialogue.

[xvi] At this earliest stage, when a love of beauty is being awakened through a singular instance, it is unclear if Plato means a beautiful person, say a mother or teacher, or beautiful works of art, or something else altogether.

[xvii] Plato, The Dialogues of Plato, 341.

[xviii] Plato, 342–43.

[xix] The historian of philosophy, Richard Kraut, helpfully explains this in The Oxford Handbook of Plato. Diotima never claims that the lover who has moved from the first to the second stage is no longer a lover of bodies…. He now sees how defective his initial response to beauty was because it excluded so much…. What the lover constantly learns as he ascends is that his outlook at each earlier stage was defective because it included too little. So, when he reaches the final stage and recognizes the greatest beauty of all, he does not stop thinking that other things—including bodies—are beautiful as well and responding affectively to their attractiveness. Their beauty may be small by comparison with that of the form of beauty, but they nonetheless participate in its beauty and because of that participation they too have some degree of beauty, however small.” Richard Kraut, “Plato on Love,” in Fine, The Oxford Handbook of Plato, 297.