How can we cultivate the virtue of gratitude when it is lacking? Can a person train themselves to actually feel grateful? Is gratitude even a feeling, or is it an act of the will.

These are some questions I want to briefly address in today’s post.

Much of the contemporary research being done on gratitude was published by Oxford University Press in their 2004 book The Psychology of Gratitude. The book brought together scholars working on gratitude from diverse fields: biology, history, spirituality, psychology, anthropology, neuroscience, etc. When reading this book, I wondered if there was some kind of synthesis or common thread that could be traced through the various perspectives. And the one thing that became clear is that gratitude involves the whole person: the will, the mind and the feelings. That might seem like an obvious point. But understanding the three-fold nature of gratitude is key to answering the question of how an ungrateful person can go about cultivating gratitude.

It will be helpful to discuss all three of these aspects, starting with the mind. I am beginning with the mind for purely organizational reasons and am not implying any psychological or logical priority in this way of ordering things. The mind, the will and the feelings all work simultaneously in a web of multiple reciprocities, but for organizational purposes it is necessary to treat them separately.

The Grateful Mind

With the mind we recognize the goodness of our life, and acknowledge that the source of this goodness lies outside the self. To be grateful is to recognize one’s debt to others, and ultimately to God, for good things we need but do not deserve.

Think of a time when you were really grateful to someone. Usually when we do this – when we think back to something somebody did that we were really grateful for – it was either when we were in need and someone helped us, or when someone gave us something we didn’t deserve. It might be a material gift we didn’t deserve, or maybe something immaterial like love, forgiveness, compassion or empathy.

A precondition to experiencing gratitude is to recognize our primal sense of neediness, and also that we don’t deserve anything. On the occasions where you felt grateful to someone, if you had believed that you were completely self-reliant without any needs that the other person met, or if you believed that the other person was merely giving you what you deserved, it is doubtful you would have been able to feel grateful at all.

So our beliefs about ourselves and the world play a key part in gratitude. The belief in our primal neediness and dependency enables us to receive good things as sheer gift. Ultimately this is to recognize that we stand in a debt position to God, and thus everything He gives us, from clean water to medical care to salvation, is pure undeserved favor.

That’s from a Christian perspective, of course. But what is interesting is that empirical data gathered by secular researchers confirms that a person’s worldview affects the degree of gratitude a person can feel. For example, compare the Christian worldview with the Aristotelian perspective. Aristotle believed that since the perfect man was completely self-reliant and stood in debt to no other person, there could be no place for either gratitude or humility. When he described a noble person who fully embodied the Good Life, Aristotle portrayed a man who remembers favors given but not favors received. For Aristotle, to have a completely noble nature was to eschew neediness, since the recognition of needs put a person in debt to others.

But Christianity recognizes our dependence on others. At some level the failure to be grateful is a failure of the mind to recognize the extent of our neediness, the extent of our dependence on others, and the extent of our dependence on God.

The Grateful Will

But while this mental recognition is a necessary condition for gratitude, it is not sufficient. It’s possible to give mental assent to the truth that we stand in debt to God and others and still not choose to be thankful. For example, one might mentally recognize one’s sense of dependency but actually resent it. Or, God-forbid, a person might be proud to have been given so many things he or she does not deserve. So it’s not good enough to simply recognize these things intellectually, we also need to make the choice to be grateful. More specifically, we need to choose to acknowledge what the mind has grounds for recognizing, and choose to offer thanks for all the good things we’ve been given.

The Grateful Feelings

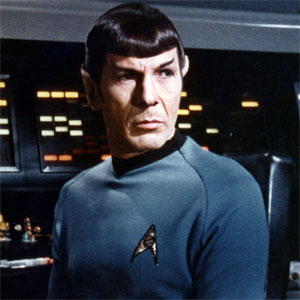

But even this is not enough. One could give thanks because it is the right thing to do and still not feel grateful. Spock in Star Trek might have gratitude at that level. But gratitude is more than just mechanically recognizing, acknowledging and giving thanks. In order to actually have a thankful disposition, in order to radiate a sense of gratefulness, one must feel appreciation for one’s blessings.

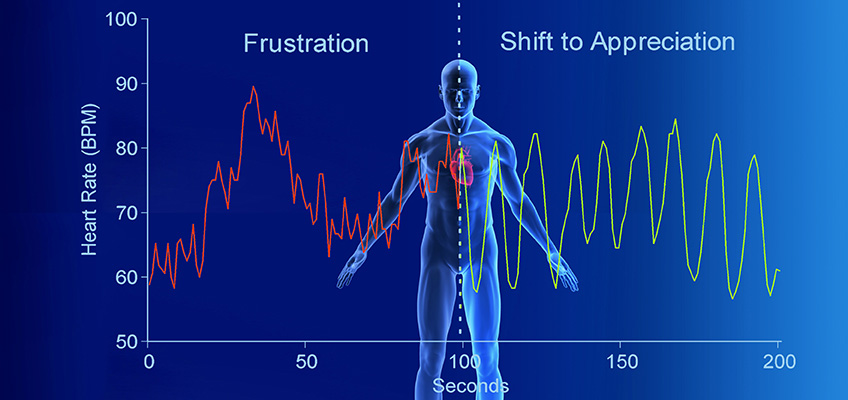

This feeling aspect of gratitude is really important. In fact, it’s probably the most important of all three. Scientists have found that when we feel a sense of appreciation to God and others, the rhythm of the heart goes into a state of “coherence” or what is also referred to as “heart-rate variability.” This is not a state of relaxation, but a state of well-being that we often feel when we’re in the presence of someone who radiates peace, compassion, stillness and inner-warmth. Having a coherent heart-rate initiates a positive web of reciprocities in the mind and body, resulting in increased mental, emotional and physical fitness.

During times of stress, including the type of stress triggered by ingratitude, the rhythm of the heart is disordered, a state cardiologists call “incoherence”. During these times of diminished heart-rate variability, the pattern of neural signals traveling from the heart to the brain is disordered, leading to a decrease in the higher cognitive functions like attention, perception, memory, emotional intelligence, problem-solving skills, and so forth. This decrease in proper cognition leaves people without the inner resources for dealing with stress, which in turn reinforces the negative emotions underlying the heart’s disordered pattern of beating.

In order to move from this incoherent condition to a state of heart-rate variability, guess what scientists are recommending? Gratitude! When we feel appreciation for the good things in our life, especially for the people who have blessed us, our heart becomes healthier, more coherent, and this spreads a sense of well-being throughout the rest of the body.

Scientists who are researching techniques for increasing cardiac health through heart-rate variability also tell us to focus on our heart-area, breath deeply and fix our attention on something we appreciate, something we are grateful for. You can also incorporate meditative techniques such as the Jesus Prayer as you breath deeply in and out. This is what scientists are saying based purely on the data.

A lot of this research is still quite new, but each year there are more and more studies. You can access a lot of these studies at the website for the HeartMath Institute. This is something people have always experienced, but only recently have we developed the equipment for measuring these processes on a biological level. And this is something I’ve experienced first-hand. Earlier in the year I purchased equipment that measures a person’s heart-rate variability. I’ve watched the biofeedback readings on myself and others change dramatically when the only changing variable was focusing on the things for which we’re grateful.

Feeling Grateful is a Skill

What many people don’t realize is that the emotional dimension of gratitude is a skill. In our culture, we tend to make a false dichotomy between feelings and skills. We assume that feelings are outside the control of our volition and thus we overlook the important ways that negative feelings can be censored and positive feelings habituated.

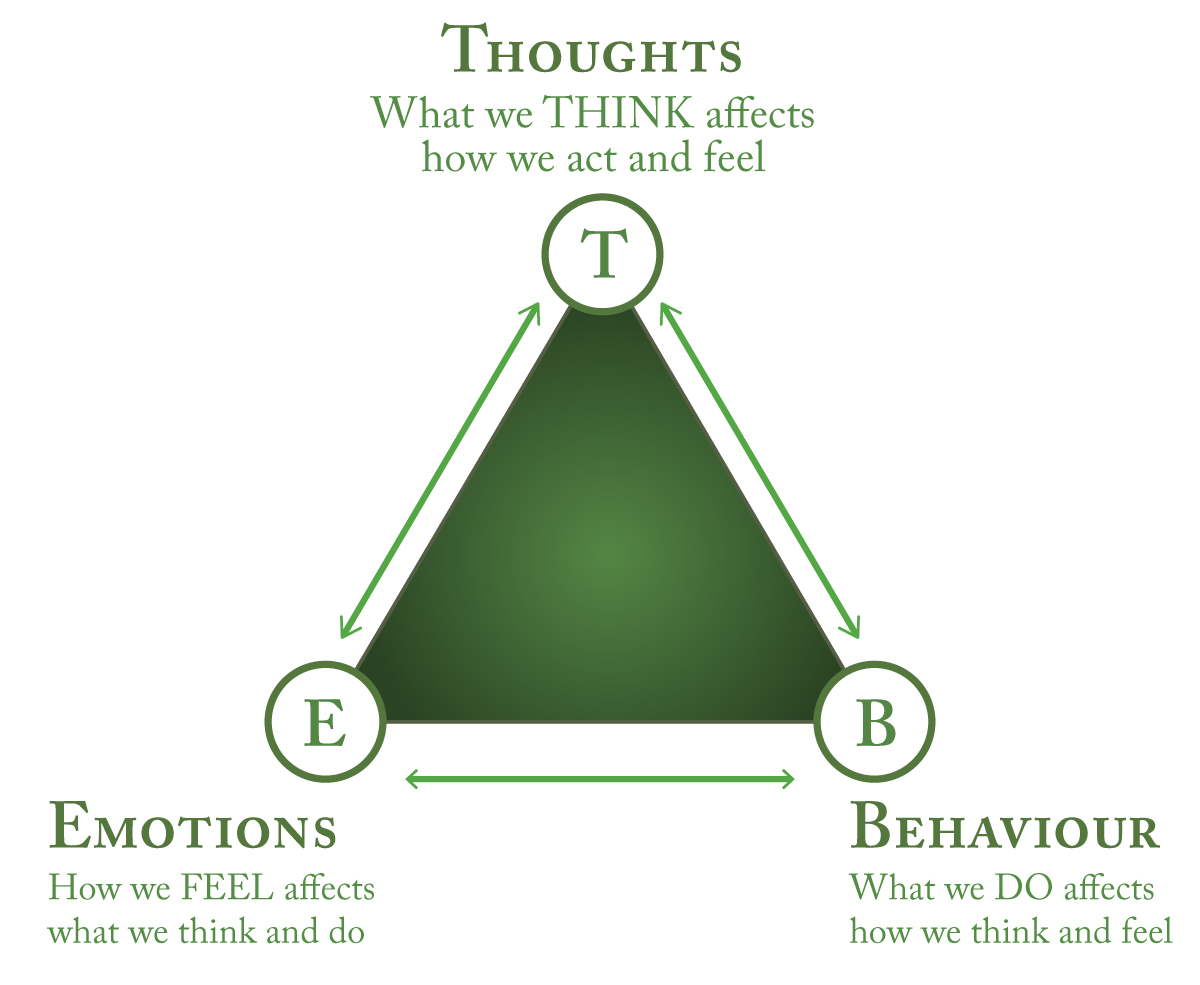

One of the great benefits of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy research has been to underscore that our emotions can be skillfully managed. The reason emotions can be managed is because of the web of interconnections between our feelings, our behavior, and our thoughts or cognitions.

Because we are whole people, and because our will, mind and emotions interconnect in complex ways, the way to transform one’s emotional life is often to first bring our thinking and our behavior into alignment with what is true and right. This principle is helpfully illustrated with this picture of the CBT triangle.

Notice these arrows running in all directions. These arrows indicate that what we think affects how we act and feel, how we feel affects what we think and do, and what we do affects how we think and feel. (To read more about the CBT triangle, visit my TSM post ‘The CBT Triangle and You.’)

The point is that our emotional states don’t just arise in a vacuum but are continually being fashioned, refined and strengthened by our thoughts and behavior. Similarly, disordered behavior doesn’t just happen, but is fueled by maladaptive thoughts and feelings. Or again, toxic thoughts don’t just arise automatically, but are continually fashioned by our feelings and behavioral priorities.

One of the reasons it’s easy to perceive our emotional life as an autonomous zone outside our volition is because we often attack our emotions head-on instead of working side-ways through the other areas. Confronting maladaptive feelings head-on, like so much psychotherapy did in the first half of the 20th century, can often have value in helping someone come to know themselves, but it can be painfully slow when it comes to actually changing one’s emotional dispositions. Such an approach is often not successful, thus fortifying the impression that emotions have a life of their own outside our control. However, it is a myth that a person can’t change his or her emotions. The way you change your emotions is via thoughts and behavior.

Being aware of the web of connections between feelings, behaviors and cognitions enable us to get out of autopilot mode whereby we are pulled along by emotions, thinking automatic thoughts, and reacting to these feelings and thoughts with maladaptive behaviors. We need to get out of that autopilot mode so that we can be deliberate over our lives and take control. And one of the ways we do this is by recognizing that what we think affects how we act and feel, how we feel affects what we think and do, and what we do affects how we think and feel.

So how does this apply to gratitude? The goal is obviously for gratitude to permeate our entire experience. We want to reflect gratitude in our emotions, our thoughts and our behavior, but we especially want to be able to FEEL grateful. But sometimes while the habit of gratitude is still in formation, we have to focus on the two other areas on the CBT triangle to give our emotions time to catch up.

Focusing on your thoughts would include such things as mentally rehearsing all the things you have to be thankful for, engaging in cognitive reframing techniques, bringing one’s thinking into alignment with reality every time you’re tempted to grumble, learning to practice mindfulness, and so forth.

Focusing on behavior could include things like keeping a gratitude journal, committing to try to make it 21 days without complaining, choosing to give thanks to God for ordinary things that you normally take for granted, developing the habit of meditation, and so forth.

By doing these things — that is, by actively cultivating gratitude in our thoughts and behavior — we create the conditions in which feelings of gratitude can flourish and eventually become habituated.

Virtue Takes Practice

This goes against deeply-held assumptions in our culture. A pervasive notion today is that to be true to yourself, you have to let your behavior follow your feelings, and that if you commit to think or do things that are contrary to how you’re feeling, that is being hypocritical. This is how love is often approached, as evidenced by so many movies today, and it is also how many people instinctively think about morality.

Consider how increasingly our society is making a virtue out of lifestyle choices that require the least amount of effort in the thinking and behavioral categories of the triangle, so that what is left is raw emotion. To the degree that emotion is treated as having a life of its own unhinged from the influences of thinking and behavior, there becomes no place to talk about training the emotions.

A

What all of this misses is that the truly worthwhile things in life all require hard work. Gratitude is no exception. There is nothing artificial, contrived or less authentic about virtues that require hard work over long periods of time. For example, we wouldn’t say that the discipline of continual inner prayer is artificial and inauthentic if it takes years to develop. In the same way, gratitude is hard work and involves painstakingly retraining the brain over long periods of time.

And the research bears this out. The research shows that gratitude is a skill that can be developed with practice and that the development of this skill is not dependent on the circumstances happening around us. Anyone can grow in this skill regardless of how bad their life is.

One of the exciting things that science is finding is that as we grow more skillful in the practice of gratitude, we actually affect material changes in the neurocircuitry of our brains that results in a healthier and happier life. Scientists who study the flexibility or neuroplasticity of brain have shown this – they’ve shown that when we practice gratitude we create new pathways in the brain, and the more we do this, the stronger these pathways become. As Eric Karpinski explains, instead of reinforcing deep ruts of complaining, so that our default response is something like “why is this happening to me?” or “who am I going to blame?”, our default becomes a narrative of gratitude. “What do I have to be thankful for?” “What’s good about today?”

When you’re just beginning to train your brain, it feels unnatural, like learning to speak in a foreign language or learning a new musical instrument. But practice it long enough, and gratitude becomes second nature. This is even possible for the most pessimistic of people, because when you choose gratitude over grumbling, new synapses form between the neurons of the brain, so that eventually it’s no longer difficult, it no longer feels unnatural. And meanwhile, if we aren’t using the neuropathways and synapses associated with grumbling, they shrivel up and go away. Living in a constant state of thankfulness to God becomes the norm.

Further Reading