Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He stared at the Pacific—and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

The above sonnet is, of course, John Keats’ “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer,” (1816). There was nothing new about Homer in Keats’ day, as it was part of the staple diet of educated Englishmen. But Keats found the translation by Elizabethan playwright George Chapman to be an epiphany akin to riches, or the new territories found by explorers.

Englishmen in the 19th century were familiar with the Iliad and Odyssey through the translations of John Dryden and Alexander Pope. But these translations were polished literary creations that tended to mute Homer’s wildness. For example, here is Pope’s translation of Iliad Book 1 line 67:

If, fired to vengeance at thy priest’s request,

Thy direful darts inflict the raging pest:

Once more attend! avert the wasteful woe,

And smile propitious, and unbend thy bow.”

This is beautiful poetry, perhaps especially appealing to Englishmen accustomed to Virgil. But these English couplets do not quite capture the dynamism of the Homeric epics, which came to the Greeks through oral transmission out of the shadowy days of their Bronze Age past. Chapman’s translation captures something of the rugged turbulence of Homer’s spirit, offering Englishmen a version that Swinburne praised for its “romantic and sometimes barbaric grandeur.”

Keats’ friend, Charles Cowden Clarke, gave him a copy of Chapman’s more earthy translation. By putting the wildness back in Homer, it transported Keats to a new world, symbolized by his reference to Darien, a destination in Panama that enabled Balboa to discover the Pacific Ocean. (Keats mistakes Balboa for Cortez, though this does not detract from the beauty of the verses.)

I was introduced to Keats’ poem by Julian Kwasniewski, a musician, visual artist, and writer who works as a spokesman for Wyoming Catholic College (WCC). The poem is a favorite at WCC, and one which all students are expected to memorize. But for students and alumni of WCC, the poem has a deeper significance than simply its role as part of the curriculum. Education today, like translations of Homer in Keats’ time, has been domesticized, out of touch with the wildness of reality. Even classical education often tends to burrow students deeper into a heady rationalism that loses touch with the wildness of the skies and the wonder of recently discovered oceans. At WCC they are trying to redress that, drawing on the more holistic pedagogy of John Senior (1923-1999).

John Senior: Reconnecting Students to Reality

Before talking with Julian Kwasniewski, I simply knew Senior as the author of The Death of Christian Culture and The Restoration of Christian Culture. But Kwasniewski explained Senior’s pedagogy, and how that has been replicated at WCC.

“When teaching liberal arts at the university of Kansas,” Kwasniewski explained, “Senior found it difficult to teach the Great Books. It wasn’t just that people had stopped reading the formative texts of the Western tradition, and it wasn’t just a general lack of cultural literacy. It’s more that we can’t read them because we don’t share the same body of experience. The modern way of life, from fluorescent lights to climate-controlled cars, has the effect of divorcing students from the natural world and even human experience. Senior believed this made it difficult for his students to relate to the experiences described in the Great Books.”

The modern way of life, from fluorescent lights to climate-controlled cars, has the effect of divorcing students from the natural world and even human experience. Senior believed this made it difficult for his students to relate to the experiences described in the Great Books.”

I asked Kwasniewski to give me an example of what he meant.

“Well, consider the experience of gazing at the stars, perhaps the primary pastime before electric lights. Star gazing forms you to think of the heavens in a certain way—the way described in texts like Beowulf, Song of Roland, even the Bible. It is a window into the infinite and the Divine. Or consider animals. For many young people today, maybe their only experience of an animal is a house cat. When you read Aristotle’s discussion about certain animals acting toward specific ends that are natural for them, that may have little meaning if your only experience of a chicken is from modern storybooks. If you never see animals hunting, hiding, mating, protecting their young, you don’t really see them acting for very clear ends. And then you might technically know every word from Aristotle’s zoology, but it doesn’t resonate with any tactile experience.”

What was John Senior’s solution to this problem?” I asked.

“While teaching his integrated humanities program at the University of Kansas, Senior realized that in order to give students access to the Great Books, he had to do more than simply ‘teach’ these texts. He had to help his students achieve unmediated access to reality – untechnological reality. He wanted them to understand from first-hand experience the description of stars in an epic poem, or the references to country dancing in an eighteenth-century novel. He wanted to help them enter into the sense of manners and pageantry described in the Arthurian romances, to share in the thought-world of poets like Hopkins and Wordsworth.”

Kwasniewski went on to explain how Senior introduced his students to God’s first book, the book of nature, by taking them on hikes and singing around campfires. He even took the students on summer trips to Ireland and Rome. They also engaged in lost cultural practices, like putting on waltzes that they would attend in full ballroom attire.

“Senior understood that we need to get into great literature the same way we get into the mountains, through immersing ourselves in the entire experience,” Kwasniewski told me. “And that means approaching texts not just as historical artifacts, but in the context of faith and community where spiritual life is strong, and where our entire person is being formed. When we’re all pursuing excellence in mind, body and spirit—trying to integrate these in a meaningful way—then we can become the types of people who can be ordered toward the good, true, and beautiful.”

Intrigued, I started reading up on Senior. I came across an article in Crisis Magazine where Philippe Maxence explains some of the other things Senior’s students would do between university classes.

Groups of students gathered to learn poems by heart. They also met their professors at night to contemplate the stars, to take courses in calligraphy, and to learn old songs—including drinking songs—which they sang in chorus. The goal was to reeducate the senses in order that these city-dwelling students might have the chance to encounter the real.

Senior also revived practices that at one time would have happened organically in the home. “Read, preferable aloud, the good English books from Mother Goose to the works of Jane Austen,” he declared in The Restoration of Christian Culture, adding, “And sing some songs from the golden treasury around the piano.”

But Senior’s Integrated Humanities Program (IHP) was not just all song and dance. It was intellectually rigorous. Each semester students had to memorize ten classic poems, attend intensive sessions on writing and, of course, study the Great Books. Michael Pakaluk tells how once a week students would attend “a drill session led by older students, to memorize names, dates, and facts.”

Although Senior’s purpose was to educate, not proselytize, he had a profound impact on the students’ spiritual lives. Pakaluk recounts how “in the brief five or so years of its thriving (1972-77) over two hundred students converted or reverted to Catholicism, many of whom later became monks, priests, abbots, and bishops.” But even those who did not convert to Catholicism or other Christian traditions still imbibed Senior’s infectious way of inhabiting the western tradition. In an interview with Kwasniewski for The Imaginative Conservative, Senior’s son Andrew reflected, “Everyone who ever met him, even briefly, was affected by his intense love of truth, goodness and beauty.”

Here’s how one of Senior’s students described the vision he caught from Senior’s teaching:

He had the vision of an eagle looking down upon earth. He could see the beauty of life in all its detail. He could teach us to seek the Good, the True, and the Beautiful in a palpable way that made us long for it, as Odysseus longed for Ithaca. His teaching was, moreover, experiential, by example, living as best he could the love for tradition that he taught.

While Senior’s methods were a success with the students at the university of Kansas, the administration did not look favorably on the IHP, which went against the canons of 20th century politically correct education. Pakaluk explains that the higher-ups at the University of Kansas were ruffled by the conversions, in addition to having concerns that the education wasn’t technical enough. Eventually, they canceled Senior’s integrated humanities program.

During my conversation with Julian Kwasniewski, he explained how Senior’s vision was later incarnated at Wyoming Catholic College after one of Senior’s former students, Dr. Robert Carlson, became one of the College’s three founders in the years 2004-2005.

Using Digital Minimalism to Reengage Reality

“Following Senior,” Kwasniewski told me, “we try to put the wildness back into the Great Books, even as Chapman did for Homer. And that means experiencing the same world as Beowulf and King Arthur—the world where we get cold and hungry, where we enjoy friendships over a fire, where we embody the virtues of hospitality and sharing. It also means removing the technologies that buffer us from direct experience of reality. WCC is famous for its digital minimalism policy.”

I asked him to explain about their approach to technology.

“Well,” Kwasniewski said. “It’s simple. We take their phones away from them.”

“You mean the classes are phone-free?” I asked.

“No, they don’t have their phones at all for school.”

“Wow,” I said. “For the entire day?”

“No Robin, the whole semester is phone-free?”

“Hunh? You’re joking!”

“The students check in their phones, and the devices are locked up in a box in the student life office.”

“Wow,” I said. “For the whole academic year?”

“Yep. They get them back for breaks, or if they need to travel for some reason.”

“Really?” I replied. “That must be difficult for the students.”

Kwasniewski answered that most students find the digital minimalism policy a relief since it frees them to offer their full attention to the Great Books, to each other, and to a rich diet of poetry (throughout the course of the four years at WCC, the students memorize forty poems).

“But,” I asked in consternation, “what if they need to get hold of their parents or make an emergency call?”

“They do it just like everyone did in the twentieth century. Their parents can phone the office and we will go find them. The student can even issue a request to the prefect to get their phone out of the box for a specific legitimate task. And there are landline phones in the dorms that students can use. You know, the old-fashioned type with a receiver that doesn’t let you get more than 20 feet away from it.”

Kwasniewski then explained that taking away their phones and restricting internet is not enough. That is just the beginning. “The real education starts when we reorient their relationship to the natural world, the realm of the senses that was so important for John Senior. That’s really the point of the digital minimalism policy. The emphasis is not on what we’re against, but what we’re for. The low-tech policy is just a means, a tool, for helping us better engage with reality.”

“Ultimately, that’s what the liberal arts are for,” he continued, “engaging with reality. They are called ‘liberal’ because they are for the free man, who is trained to use his liberty to develop the capacities that make us uniquely human, especially our wonder, reason, intellect, and imagination. For a human being to flourish, all of these have to be integrated with each other, which is why a purely academic approach to the liberal arts—one that offers only head-knowledge while neglecting the students’ relationship to the natural world—is ultimately oxymoronic.”

Helping students have a right relationship with the world of the senses begins with freshmen orientation, which involves putting the wildness back into classical education. And when I say “wildness” I mean it literally.

A Wilderness Orientation

Freshmen orientation consists of a twenty-one-day backpacking expedition into the wild. Following a week of preparation, including gear familiarity, survival skills, and wilderness first aid, students are taken deep into the Teton or Wind River Mountain Range. These expeditions are sex-segregated and split into groups of a dozen. They are led by juniors, seniors or alumni who have already been through the program and learned the skills and gained certifications in emergency medical care and wilderness guiding. Upperclassmen are also required to take two weeklong trips, either canoeing, kayaking, rock climbing, repelling, or white-water rafting.

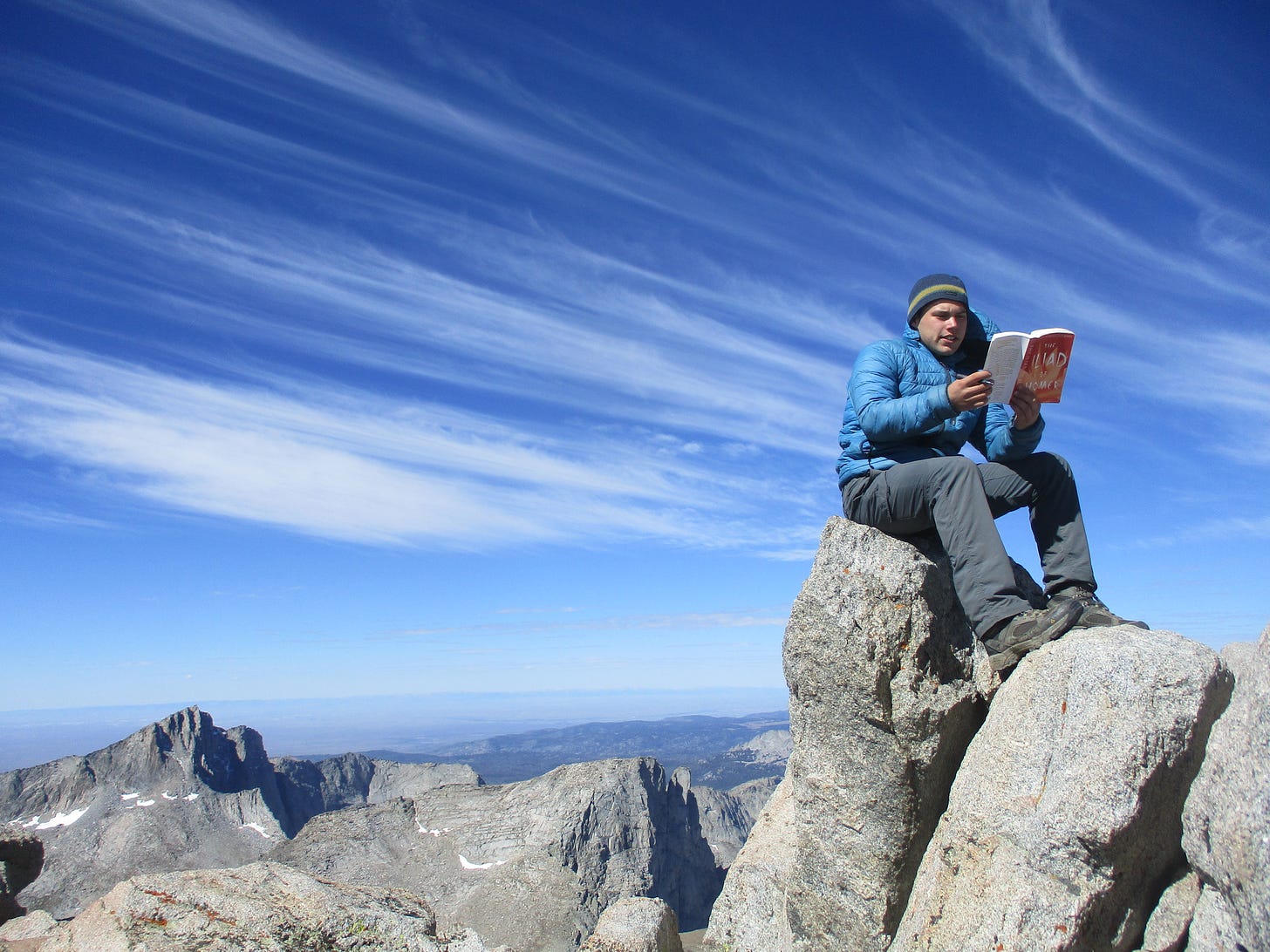

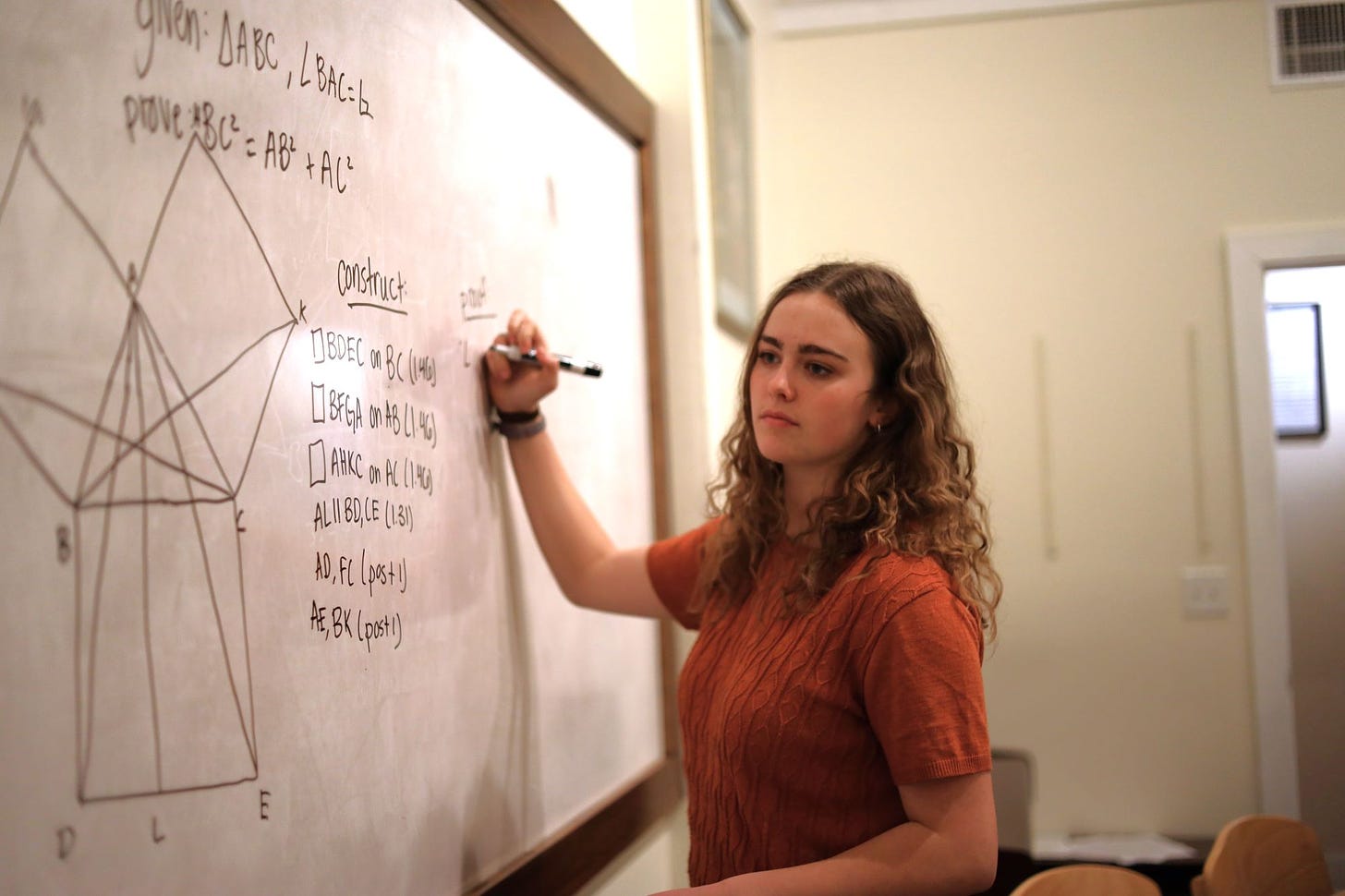

Here are pictures from some of the expeditions.

.

.

.

In these expeditions the students learn how to navigate with a paper map and compass, how to keep food away from grizzly bears at night, how to engage in risk management, conflict resolution, decision making, and leadership skills (students take turns being team leaders). But more than simply learning skills and virtues, these expeditions offer the students a common experience of reality they can later draw on during their studies at WCC.

I asked Kwasniewski how the times in the wilderness inform the academics at WCC. Here’s how he explained it.

If you’re in the classroom studying some of the deepest questions of man’s existence (say, Aristotle’s idea of the virtuous man), you can discuss that in light of the shared experiences you’ve made with your friends in the mountains and around the campfire. Out in the wilderness, the virtues are not just abstract subjects; you have to live them if you’re going to survive. There are so many situations the students encounter that become a pressure cooker for the virtues. For example, suppose you accidentally left a granola bar in your sleeping bag (a sure way to attract a grizzly bear) and so you have to wake someone to help you put it in your food cache eighty feet away in the dark. If you’ve never had to deal with these types of situations, how can you have a context for discussing the virtuous life?

I think WCC is onto something important. For students who are used to clean and predictable environments, getting into the back country helps them experience an integration of mind, body, and soul that you can’t achieve just by studying it. The backcountry is a place where you don’t have control, where you might be hit by a storm and suddenly have to get into lightning safety position, and where your very survival depends on hard skills and virtues put into practice. These hikes give the students a direct experience of reality that just isn’t possible if reality is being mediated through electronics, or even textbooks that turn the study of reality into one more academic subject.

Moreover, these expeditions provide a common body of experience for appreciating many texts they study, perhaps especially the forty poems they memorize. For example, if you’ve never sat around the campfire at night, can you really understand what Hopkins meant when he used fire as a metaphor for understanding kingfishers and dragonflies? Or what did Shakespeare mean when his Henry V refers to his company as a “band of brothers” on the eve of the Battle of Agincourt? It’s one thing to read about community, and quite another to actually experience it.

“Orientation in the wilderness forces students to make a miniature community work,” Kwasniewski told me. He continued:

It has to work or you won’t survive. And by experiencing community the students learn something important about reality itself. When you’ve been hiking at 10,000 feet in the hot sun with a 50 lb pack on your back, you simply don’t have the energy to put up barriers between yourself and reality, including the reality of other people. Sometimes there are arguments, sometimes students break down and cry. This discomfort is important for making us real. Discomfort is not an end in itself but it is a frequent companion of the real.

In our modern world we have so many ways of buffering ourselves against discomfort, just like in Huxley’s Brave New World. Whenever anyone in the story started feeling the least bit existential, they could take the soma pills and felt better. But we essentially do that with tech. We have a soma machine in our pocket, which can always be pulled out to sedate ourselves. When you take the phone away, then you have to face reality.

As you can imagine, I was pretty fascinated by this, avid hiker that I am. Kwasniewski invited me to come along on one of the trips, an invitation I hope one day to accept. In the meantime, I asked Kwasniewski to put me in contact with some students, as I was eager to hear their perspective on this rather unusual education.

“Tuned In” to Moments of Joy

One freshman I spoke with, Augustine McDermott, told me that he struggled with the orientation experience. “The initial backpacking trip was incredibly unpleasant,” he said. “I was forced to take responsibility for other people in a way I never had before. That environment led me to bond with the guys faster than I had ever made friendships before.”

Here is a photo of Augustine from last semester, reading The Iliad on top of Wind River Peak at 13,200 ft elevation.

When asked about the digital minimalism policy, McDermott told me that it had been incredibly freeing for him. While in high school in Pittsburgh, he had always struggled with his phone, and engaged in all the rituals of would-be digital minimalists such as deleting apps during Lent, turning off notifications, and trying to muster will-power not to constantly check for incoming messages.

“Sometimes I would try to give up watching YouTube for a while,” he explained, “but even during those times I would fall back into habits of dependence. I’d check my phone for messages first thing when I woke up, and I never left the house without my phone.”

When McDermott entered WCC with the class of 2027, he welcomed the digital minimalism policy. Yet he never really expected that it would change his life. Very quickly he found that the absence of a constant connection did more than merely free his mind from distractions. Rather, the absence of the phone created empty spaces in his life and mind that could be filled serendipitously by what we now refer to as “traditional activities.”

“Small moments that would have been filled by my phone now create a matrix for casual conversation: checking in with people to see how they are doing, or informally continuing a discussion from a class, or even spontaneous poetry recitation. In a low-tech environment, it’s far easier to get pulled out of yourself.”

I asked McDermott to give me an example of the type of spontaneous interactions that occur when there are no phones around.

One night I was quietly studying when a troupe of maybe fifteen students came skipping through the room singing a Latin round. I put my homework to the side and joined them in parading all over downtown, singing folk songs, polyphony, and rounds for about a half an hour. I feel like that anecdote expresses the way this environment is a matrix for community. Everyone is “tuned in” to moments of joy, because they are not constantly tuned into the online world accessible through phones.

.

.

.

Because the school is in Wyoming, the students have particular opportunities to participate in outdoor activities, from horseback riding to winter hikes in the snow. As is often the case, priests accompany the students on some of their longer expeditions. During their winter trip, the students build snow altars for their daily Mass (at WCC, spiritual formation is just as important as intellectual and physical training.)

.

.

.

Unbundled Education and the Challenge of Slow Traditional Culture

My initial interest in WCC was because of their digital minimalism policy, since there are chapters about that in my forthcoming book, We’re All Cyborgs Now: Technology and the Christian Faith (Basilian Media & Publishing, 2024). But the more I became familiar with WCC, the more my interest shifted from what they were against to what they were for: specifically, the type of traditional activities John Senior encouraged and which have become an organic part of the WCC culture.

I have often found myself wondering if one of the reasons so many people are drawn to the canonical texts of our tradition is not simply because these are great works of art, but because these texts offer a glimpse into a more humane way of life largely lost to moderns. Princess Nausicaa’s introduction to Odysseus while washing clothes on the seashore is more than just a wonderful piece of dramatic tension in the Odyssey; it shows a way of life foreign to those whose serendipitous encounters at the laundromat may rarely rise above bumping into someone because we are staring at our phones. The country dance scene in the second chapter of Tess of the d’Urbervilles is endearing, not merely because Thomas Hardy is a descriptive genius, but because a dance on the village green seems like a lost world to those whose only experience of dancing may be EDM at the local night club.

Of course, the smartphone is a culprit in the erosion of traditional activities. Even as recently as the 90’s, I remember seeing teenagers regularly playing in the street in ways that now seem quaint. However, I think we often miss the deeper reason why our phones make traditional activities difficult. At one point I thought that the challenge digital interfaces pose to traditional activities—whether playing in the street, sitting around a campfire, or singing together as a pastime—is the challenge of distraction. While this is certainly true, it is an incomplete assessment. Our phones do more than merely distract us: they turn us into junkies on the constant lookout for fresh stimuli. This, of course, reorders what we expect from traditional activities. Through the constant tutelage of our digital devices, it has become second nature to approach traditional activities as merely delivery mechanisms for pleasurable hits. When traditional activities become thus instrumentalized for pleasurable sensations, anything not essential to the dopamine spike becomes mere window dressing that can be unbundled and disposed of. For example, if the pleasurable feeling of viewing a beautiful mountain top can be unbundled from the struggle to climb the mountain, then why bother climbing the mountain at all? If the pleasurable feeling of intimacy with another person can be unbundled from the struggles and hardships of a relationship, then why bother with the relationship at all?

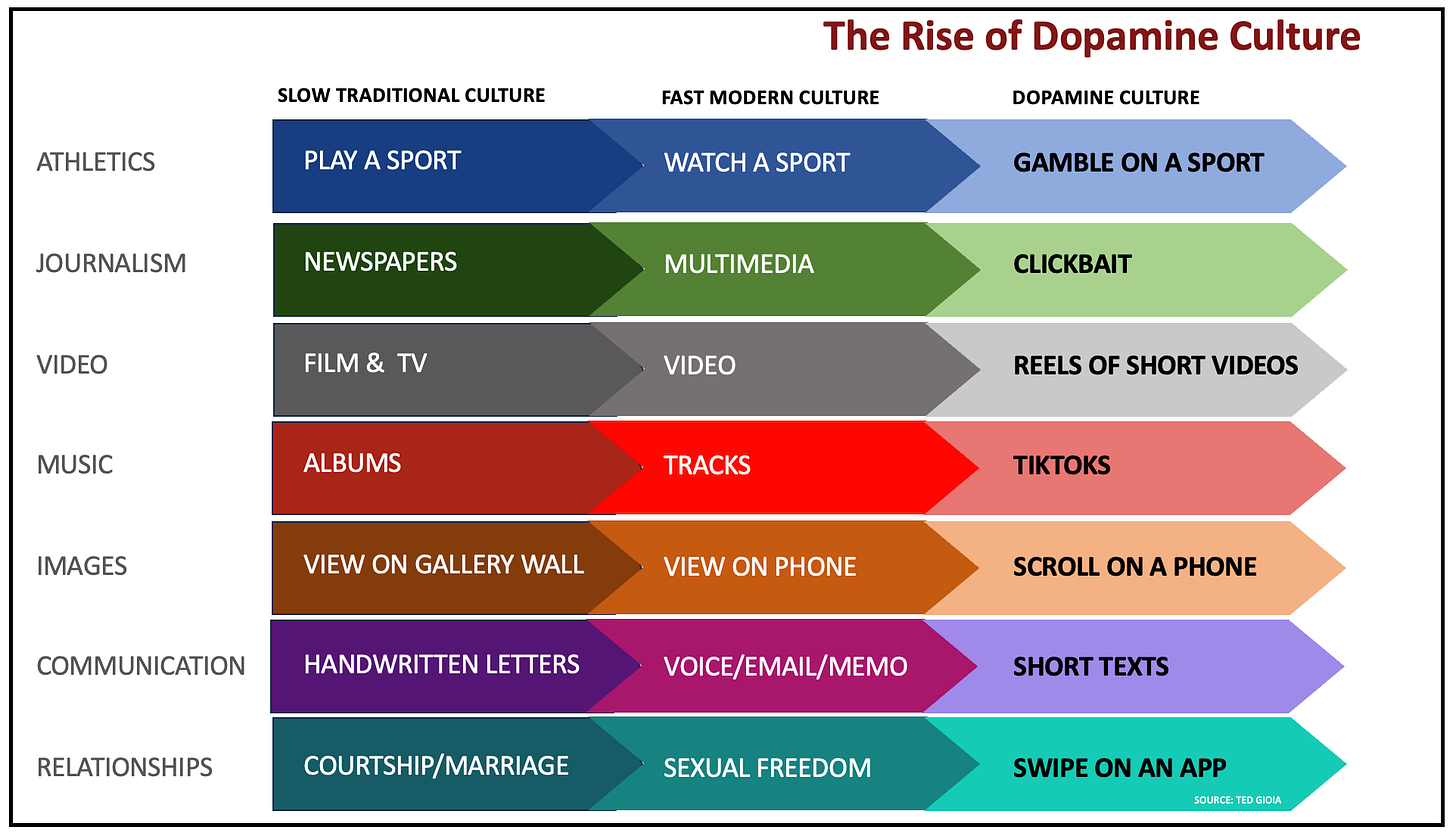

The unbundling process is all around us. In the music industry it is now routine to buy a specific track without the entire album, or to listen to a single movement of a symphony or concerto outside the context of the entire work. Journalism was unbundled long ago when newspapers went digital and reporters started being trained to focus their writing toward search engines and page views rather than to craft their stories in a way that might only make sense in the context of the newspaper as a whole. Film was unbundled when YouTube enabled viewers to watch the best scenes from their favorite movies without needing to wade through the entire film. And now dopamine culture continues this unbundling process in ways that would have seemed perverse even ten years ago. As Ted Gioia described this in a much-discussed Substack article from February, “The State of the Culture, 2024”:

Even the dumbest entertainment looks like Shakespeare compared to dopamine culture. You don’t need Hamlet, a photo of a hamburger will suffice. Or a video of somebody twerking, or a pet looking goofy.

Instead of movies, users get served up an endless sequence of 15-second videos. Instead of symphonies, listeners hear bite-sized melodies, usually accompanied by one of these tiny videos—just enough for a dopamine hit, and no more.

The ultimate unbundling occurs when the activities of traditional culture are replaced by the substitutes of dopamine culture. Ted Gioia represented this diagrammatically:

The significance of this progression is not just that the activities in slow traditional culture become replaced by fast-paced substitutes, nor that the items on the right are merely an intensification of what those on the left had to offer. Rather, activities in “dopamine culture” hinge on the conceit that we can extract what makes the traditional activities meaningful and then isolate those benefits, as if traditional activities were merely instruments for a feeling that can more efficiently dished-up in a stripped-down digital version. We begin to think that a barn dance is just a really inefficient proto-dating app. Indeed, the liturgies of our phones orient us to imagine that the full context of traditional activities is merely a husk that can be thrown away once the kernel inside is accessed. Yet the context of sport is not simply a husk to get at the supposedly real point, namely the dopamine rush we get from playing games and which might just as well be achieved—and achieved better—through gambling. The context of an embodied relationship through the stages of courtship, marriage and continual commitment is not just a kernel containing the husk of sexual pleasure that might just as well be achieved easier and better through one’s phone. The context of the activity is the point.

Now let’s apply this principle to education.

How Classical Education Got Off Course

One of my critiques of the modern classical education movement is that it often treats the Great Books as if they can be unbundled from the entire experience of reality and then dished up as a product. In this case, it is not dopamine hits that are sought but various goods that classic literature and languages are thought to convey, everything from getting a head start on college to winning the culture war to making students smart. Classic literature and languages are reduced to merely a delivery vehicle for goods that are understood instrumentally. The absurdity of this becomes evident in “online classical education” with its ethic of disembodiment, or other forms of purely cerebral learning, that sanitize classical education, unbundling it from the rich and unpredictable world assumed by the authors of the Great Books. The classics become simply an academic subject that can be disengaged from a broader experience of reality, from good habits, from the holistic integration of body, mind, and soul. But as John Senior realized, this rationalistic approach to texts means that the modern student is not actually invited to inhabit the same world as the authors, artists, and sages being studied. If one were studying a text in a different language, one would need to learn the tongue; similarly, to truly understand the Great Books even in translation, we need to enter into their world by realigning ourselves with a correct relationship to physical reality.

One of my critiques of the modern classical education movement is that it often treats the Great Books as if they can be unbundled from the entire experience of reality and then dished up as a product… The classics become simply an academic subject that can be disengaged from a broader experience of reality, from good habits, from the holistic integration of body, mind, and soul.

Can you really appreciate Beowulf if you don’t know what mead tastes like or have never got dirty? Can you really enter into Odysseus’s struggles if you’ve never tasted goat’s cheese, felt the splash of the salty sea on your face, or been in a situation where you depend on others for your survival? Can you really appreciate Herbert, Wordsworth, or Hopkins if you are so overloaded with homework that stillness is simply an idea you read about in Josef Pieper but never actually experience? And what is the point of learning how to say the Latin equivalent of “fish,” “cow,” or “chicken,” if you have never actually seen a live fish, touched a cow, or observed the comedic seriousness of chickens?

Once I was tutoring a high school student who had been assigned the Iliad and the Odyssey for “online classical homeschool.” With the pressure to get through an insane number of texts that semester, the student had only a few weeks to complete Homer’s epics, while trying not to fall behind on all his other classes and commitments. As you might expect, the student’s entire focus was not the text at all, but task completion: reading through enough pages of Homer to keep on schedule.

I went to his teacher and said, “This is a ridiculously fast and unrealistic reading schedule. It’s like trying to take a drink from a fire hose. What I propose is this. Let’s not try to get through all of the Iliad in the next few weeks, but instead let me take him up into the mountains to spend the whole day just on the scene when Odysseus is in the cave of the cyclopes. It’s a remarkable story, and if we slow down and take time to really enjoy that scene (perhaps reading it more than once), he’ll remember it all his life. But as things currently stand, it’s like trying to take a drink out of a fire hydrant.”

I was given the green light on my proposal, including doing it in the mountains, but there was one condition: we mustn’t fall behind. The student refused to go on the hike with me, knowing it would make him even busier the next day. How sad that Homer had become merely a subject to race through – one more chore in the endless cycle of task completion.

Slow Down, Look, Listen

“A rich and healthy experience of the sensible world is needed for one to know God well,” writes Fr. Francis Bethel in John Senior and the Restoration of Realism. Fr. Francis continued:

We have to “taste” the goodness of things, Senior says. That requires time and leisure. “If you jump from rocks to God,” he writes, “without a long, sensible, emotional, willful, thoughtful intercourse with them, your understanding and love of His goodness and greatness will be proportioned to the meager experience.” The need for experience exists, of course, not only for knowing God. We must also experience, know and love beautiful things to form an authentic idea of beauty, and be familiar with individual men, flowers, horses and wood for real and rich notions of them.”

This type of direct experience of reality requires us to unplug and take a contemplative turn. This is perhaps especially true if we are engaging with Homer. To really get inside Homer’s world, to share with Keats the experience of “some watcher of the skies / when a new planet swims into his ken” we need to slow down. How slow? Slow enough to begin seeing ordinary things in a wonder-filled light, in all their wildness and glory.

Consider Homer’s description of Achilles’ shield in Iliad book 18. Crafted by Hephaestus at the request of Achilles’ mother Thetis, it is a remarkable work of art, showing an intricate design that situates human affairs within the symbolism of the cosmos. The very center of the shield depicts earth, sky, sea, the moon, and some of the key constellations familiar to the Greeks. Moving outward from the cosmos in the center, there are additional scenes portrayed in concentric circles. The shield depicts the ordinary life of mankind, from great cities and kingdoms down to workers gathering the harvest and a dance where young men and maidens court each other. To Homer and the tradition he represented, ordinary life is glorious because situated in a larger cosmic drama. Ordinary life was just as beautiful as the moon and stars because all things were connected in a beautiful tapestry of significance.

You don’t need to return to the Homeric age to participate in this cosmic drama. You don’t need to start washing clothes in the river rather than the laundromat, let alone sowing seed with oxen instead of a tractor. You don’t even need to enroll at WCC. There are moments of glory and splendor all around us if we slow down sufficiently to notice.

In my previous article, “When the Machine Stops We Still Have Each Other,” I described how times of emergency often help us to reconnect with the things that matter most. But we don’t need times of emergency to tune into the joys around us. Sometimes all we need to do is turn off our phone and start looking around. Here are some suggestions I offer in the spirit of John Senior, WCC, and Homer:

- Consider occasionally going to sleep early enough so you can wake up with the sunrise. For me, there is something very grounding about starting my day outside waiting for the sun to appear.

- Instead of trying to read as many books as you can, spend a long time with just one book or poem, and then memorize the parts that are meaningful to you.

- Find times of the day for being unplugged. Set those times aside for doing the things that matter most to you, such as prayer, art, or conversation with a loved one.

- Submit to the rhythm of the day and night by using orange light bulbs (or better yet, candles) in the evening, and limiting white light to the day. Consider getting a blue-light blocker on your computer (my favorite is f.lux) to replicate the movement of the sun in your area.

- Instead of paying for expensive activities or services to reconnect with stillness—yoga sessions, mindfulness classes, relaxation apps on your phone—simply go outside, sit on the ground, and spend some time breathing deeply. Stillness is marketed as a luxury good, but it is always just one breath away.

- Find your own ways to practice digital minimalism, leveraging your phone to connect with others but not thrill-seeking. Too much thrill-seeking makes ordinary life seem boring by comparison. Learn to find satisfaction in the gentle beauty all around, from listening to the birds to watching the sunrise to enjoying the silent presence of a friend.

- If you are an educator, experiment with ways to connect your students to reality: to animals, mountains, rivers, community, and the rich and fascinating world of the stars.

This article originally appeared in my Substack, The Epimethean, and is reprinted here with permission of the author (me).