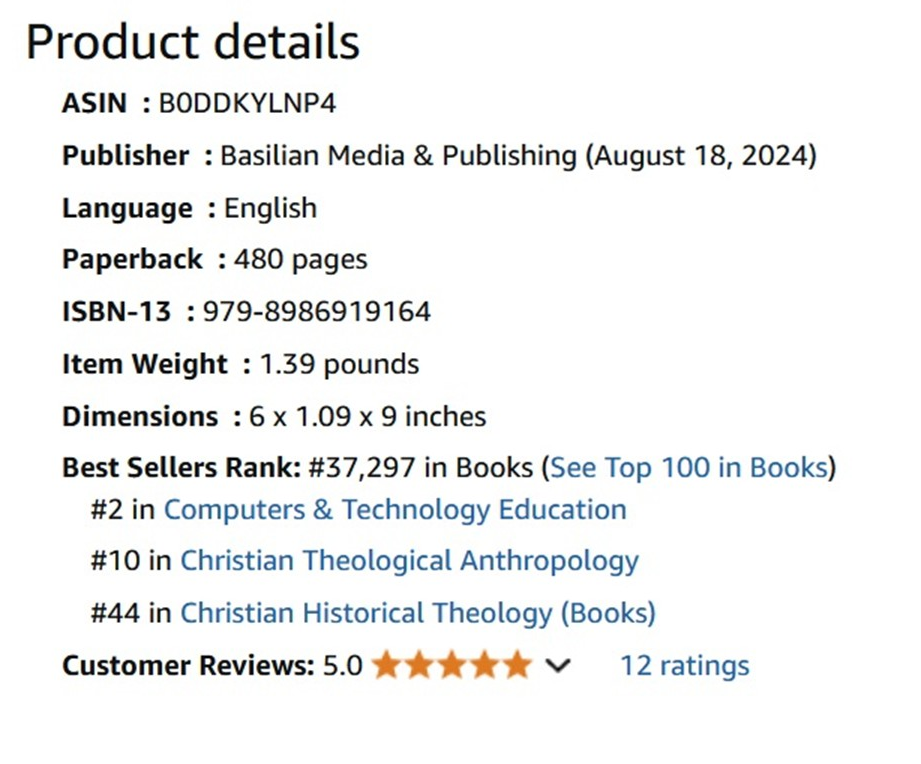

This book, which chronicles the creeping digitization of everything (including ourselves), returned to the Amazon best-seller list, achieving #2 for computers and technology education, and #10 for Christian Theological Anthropology.

- “Once I started reading this, I was drawn in. In this series of incisive, interlocking essays, Phillips and Pauling distill wisdom from tech critics, theologians, and poets to help us discern how to live as humans in a world being ordered to artificial intelligence.” —Jeffrey Bilbro, Grove City College

- “The turn away from physical reality to the digital ecosystem is now so commonplace that it seems normal.’ If this claim seems over-stated, you need to read this book. The prose will engage you and convince you that it’s under-stated. We are all cyborgs now. Not merely because of advances in technology, but because of changes in our belief in what it means to be human.This is an important book, beautifully written, many-sided, and nicely organized. Once I started reading it, I couldn’t put it down.” —David V. Hicks, author of Norms and Nobility.

- “Evolutionism: … creatures constantly losing their shape.” That Chesterton aphorism came to mind when I read in Phillips and Pauling that “the smartphone has created a situation where everything bleeds into everything else.” Their book faces squarely the impact of a technology-induced evolution that threatens to cause humans to lose their shape.” – Douglas Farrow, McGill University

- “Phillips and Pauling offer something that many of us never received in our primary or secondary educations: a philosophy of technology, and one that is rooted in the tradition of Christian metaphysics….It’s about time we have a resource that helps us resist the Machine and learn how to live as creatures made in the image of God.” — Devin O’Donnell, Vice President of the Association of Classical Christian Schools.

- “Phillips and Pauling have written a work of such argumentative clarity and cumulative evidence that one may sincerely hope their message will penetrate the minds and hearts of those who need to hear it.” —Peter A Kwasniewski, author and speaker“Without a doubt, this is the most comprehensive contemplation I’ve read on the topic, and beyond simply admiring the problems that come with technology, Phillips and Pauling provide their readers with hope and a way ahead to successfully deal with technological advances that easily overwhelm most of us.” — Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Braszko, Jr.

- After all, what does it mean to be human if not to struggle toward the good in communion with one’s fellow men and women? If you have at times felt lost, disoriented, or fearful in recent years as ever more transformative, disruptive technological products and tools come to market, then read this book and journey toward the good together with its authors…. In reading this book you will encounter two minds alive to the world and its goodness and its peril. To encounter such minds is always a worthy pursuit. — Jake Meador, author and public speaker

In addition to the above endorsements, academics have been talking about the work at conferences and podcasts. For example, Aaron Weinacht, history professor at the University of Montana, featured the book on his podcast New Books Network, while C. Ben Mitchell from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School spoke about the book in a Theological Symposia at the LCMS seminary in St. Louis (the recording is here and the discussion of our book begins 20 minutes into it).

Popular podcasters are also excited about our work, including Shanda Fulbright of the Her Faith Inspires Podcast, Anna McLaughlin in the Overwhelmed to Overcomer Podcast, the Kyle Whittington’s podcast, the Y4Life podcast, and Abdu Murray’s podcast, and Kyle King of Barrel Aged Faith (who also featured the book as a runner-up for the Barrel Award).

On Friday the book received a favorable review in The Lutheran Witness, which included the following:

Are We All Cyborgs Now?, a rigorously researched 453-page tome that draws from philosophy, Scripture, theology and literature, makes two extremely needed contributions to the popular discussion about the internet and digital technology: First, it tackles the issue from an orthodox Christian (in Pauling’s case, LCMS Lutheran) perspective, taking up the theological and anthropological questions behind digital technology rather than just its impact. Secondly, enabled by its orthodox Christian viewpoint, the book goes where many books on the topic do not and cannot: In its final section, “Being the People of God in a Technological Age,” it offers practical advice for Christian life in this context, including suggestions for technology boundaries to set with children (and with ourselves). As Pauling puts it in the introduction, “We want to do more than merely curse the darkness; rather, we want to light a candle”.

The book has also featured in various magazines and websites. Front Porch Republic printed an interview with Joshua Pauling about the book, while Kyle King referenced the book in his Substack article, “Some of the Best Books Published ’24,” and Dr. Brad Littlejohn referenced the book in his Commonwealth Dispatches, noting, “This is an extremely rich and thoughtful book thus far, offering many of the same insights of Barba-Kay’s A Web of Our Own Making, but much more accessibly, and grappling with a lot of similar themes that I’ve been talking about in this Substack over the past few months.”

Meanwhile, Pauling continues to build on this momentum by publishing widely about how Christians can approach our technological challenges with discernment. Some of the outlets where he’s been active include Public Discourse: The Journal of the Witherspoon Institute, and Voegelin View, and The Savage Collective and Modern Reformation. Additionally, he did an excellent two-part series on classical education and AI at New Aberdeen College (Part 1 here and Part 2 here). Though I have been less active, I have a chapter about classical education and AI coming out in St. Vladimir Seminar Press’s forthcoming anthology, Into the Light: Orthodoxy and Classical Education. This chapter will synthesize many of the concerns addressed in Are We All Cyborgs Now?

Mr. Pauling and I are being asked to speak on the issues of the book at various venues, and some of these sessions have been recorded. For example, you can listen to Pauling’s talk at the Consortium for Classical Lutheran Education, where he addressed the impacts of digital technology in the classroom while offering strategies for engaging with AI from the perspective of the classical tradition. He also spoke on “Christ vs. AI and Transhumanism” at the 2024 Higher Things Youth Conference at Concordia University, though that talk was not recorded. I have also been doing some presentations and have been asked to present on digital addiction at the 2025 OCAMPR conference on October 2-4, and the Paideia conference in June, where I will be giving a presentation titled, “The Metaphysics of the Machine and the Quest for Digital Transcendence.”

I was recently asked to give a 4-part adult Sunday school series on the content of chapters 30 and 31 for St. Patrick’s Orthodox Church in Bealeton Virginia. Since these classes were not recorded for public consumption, and I recorded the content myself and put on YouTube at the links below:

- Digital Boundaries for Healthy Living (Part 1)

- Digital Boundaries for Healthy Living (Part 2)

- Digital Boundaries for Healthy Living (Part 3)

- Digital Boundaries for Healthy Living (Part 4)

Why all this buzz about the book? I think part of the answer has to do with the fact that rather than adopting a reactionary posture toward growing digital omnipresence, Joshua and I help are offering Christians resources to adopt a thoughtful perspective that avoids either uncritical rejection or uncritical accommodation. Those resources are drawn from history, theology, philosophy, and neuroscience. So rather than merely offering one more narrative stirring up fear about AI, technological addiction, technocracy, etc., (though we do present a lot of scary information, from how smartphones permanently damage the brains of teenagers to what our society and politics will look like once we’ve achieved full AI integration), the main focus of the narrative is how we can live in a technological age while ordered toward higher goods. The re-ordering of our affections is two-fold. First, we need boundaries and limits, including ways to block those aspects of technology that are dehumanizing and addicting. But secondly, our hearts need to be stirred by a more beautiful vision than what the techno-utopians of our world can offer.

This two-fold way is represented by the twin stories of Odysseus and Orpheus. Most of us are familiar with the sirens, the birdlike women who lured sailors off course through music so hauntingly beautiful that no mere human could resist the bewitching call. Odysseus navigated around the siren’s isle through boundaries and limits (for example, by ordering his men to block their ears with wax and to tie him to the mast). Odysseus, perhaps aware of his tendency to forget what truly matters and get diverted off course (i.e. remember that his crew reminded him to leave the enchantress Circe and continue the voyage), takes no chances.

For many years I have been inspired by Odysseus’s heroic struggle, as has my co-author Joshua Pauling. But Chesterton Cobb (my Luddite friend whose conversations were influential when writing this book) drew our attention to another Greek hero, Orpheus, who used a very different strategy. When passing in hearing-distance of the sirens, Orpheus drew his lyre and played music more beautiful. One might say that Orpheus cultivated a positive vision that made the sirens’ song pale into insignificance.

In Are We All Cyborgs Now?, Joshua and I argue that both heroes, Odysseus and Orpheus, can guide us in responding to the challenges of an increasingly technocratic age. Yes, we need properly curated environments and routines that bind us to good habits, just as Odysseus bound himself to the mast. That is why our book offers an entire toolbox of strategies to achieve digital minimalism in the home, and thus resist the siren call of everything from online porn to sexting.

But even more importantly, we need to follow Orpheus in cultivating a more beautiful vision than what our tech-saturated society can offer. Accordingly, our narrative aims to guide readers to rediscover what is truly beautiful about embodied creaturely life so that the bewitching call of digital saturation, techno-utopianism, and digital amusements are seen as ugly by comparison.

When framed and understood within an intentional positive vision, even the forms of self-denial and self-discipline that we practice have a larger purpose, pointing us towards higher goods and ultimate ends. Then even self-imposed limits become a joy and are actually invigorating and liberating.

What is this more positive vision? Ultimately, it comes down to understanding the type of creatures we are and the type of world in which we live—in short, anthropology, cosmology, and metaphysics. Consider, when God made the world, he spoke meaning into the void of non-being, and he gave form to chaos. When God created men and women, He gave us the vocation of sub-creation, that we too might continue speaking meaning into chaos to make all of the world habitable for divine presence in an ever-unfolding doxology of movement from earth to heaven. Following St. Dionysius the Areopagite and St. Maximus the Confessor, Dr. Timothy Patitsas describes this movement as follows in The Ethics of Beauty:

God was so good that his goodness could not be contained within himself. It poured forth “outside” himself in a cosmic Theophany over against the face of darkness. The appearing of this ultimate Beauty caused non-being to forget itself, to renounce itself, to leave behind its own ‘self’ (non-being), and come to be. All of creation is thus marked by this eros, by this movement of doxology, liturgy, and love. Creation is a movement of repentance out of chaos and into the light of existence.

This primordial pattern at the heart of reality means that to be human is to have an upward yearning to unite with God, the plentitude of all being and the source of true happiness. But this desire to unite with God frequently misfires onto impulses, visions, and schemes that promise heaven but which actually have the status of non-being. These visions include the following axioms of digital utopianism, all of which are now being widely advocated by leading technologists and venture capitalists:

- we can build something that will connect us to non-human intelligences;

- through this connection we will achieve unprecedented powers, and regain the mastery over nature lost at the fall;

- this will essentially lead to utopia – a type of secularized Eden.

All three of these premises are now explicit in the various manifesto’s and policy statements of engineers and venture capitalists in Silicon Valley, as we show in Part 3 of our book. These impulses of digital utopianism lure us with counterfeit beauty precisely because they are parasitical on the primordial vocation to unite with God. But this counterfeit beauty—which now has its own pseudo-mysticism, eschatology, and redemption motifs as Silicon Valley takes a quasi-spiritual turn—leads not to life but to death. The result is that sinful passion is being institutionalized within the societal infrastructures currently built around machine-dependence.

Passions have the status of non-being because evil is a privation of the good, and a misdirection of our primary longing for God. Thus, sin structures our lives according to surrogate teloi in a kind of parody of creation and reverse-sacramentality. This reverse-sacramentality is now seen at the societal level as passion metastasizes in the institutions that frame so much of our experience of the world.

But the message of the gospel is that God has again hovered over our world and descended into the chaos: first the darkness of the Virgin’s womb, then the darkness and chaos of 1st century Palestine when the God-man walked the earth, and finally into the darkness of the entire world as the Church advances New Creation into every nook and cranny of culture and geography. Through this pattern of descent, divine beauty lifts us heavenward, repairing the broken link between earth and heaven, the material and the spiritual, the sensible and the noetic.

Through repentance we cooperate with God’s new creation energies in speaking life into the non-being of our hearts, in order that the chaos of our disordered souls might become habitable for divine presence. When we engage in this type of creative repentance, we participate not merely in our own healing, but also in the healing of the cosmos.

When things go wrong in our lives—when we get sick, experience poverty, lose our youth, watch loved-ones suffer, lose our jobs to robots, or come face to face with our own looming death—this can lead either to despair or to further voluntary self-emptying as we invite God to hover over our darkness and fill us with His life. In addition to faith and works of charity, that self-emptying may involve everything from breath prayers that reorient our attention back to God, to networks of spiritual mentoring, to monastic retreats, to bodily postures, to liturgical seasons that catch us up in the drama of redemption. At other times, this self-emptying can be as simple as pressing the off switch, or turning your phone to airplane mode. The purpose of all these self-emptying activities is not to negate ourselves but precisely the opposite: to invite God to fill the darkness of our chaotic soul with His divine life, and thus make us more fully ourselves, more fully the man or woman He intends us to be throughout all eternity.

We can participate in God’s self-giving by making our hearts habitable for God’s presence, so His Spirit can guide us on the journey to our true homeland of perfect beatitude. That journey will be full of perils and hostile creatures, as was Odysseus’s journey. And it will be full of diversions that tempt us with forms of non-being posed as counterfeit beatitude. For Odysseus, diversions came in the form of actual creatures: the sirens, the lotus eaters, the enchantress Circe, and the Nymph Calypso. For us, diversions comes in the form of digital distractions on our phones and laptops, and the larger infrastructures of machine culture that now dominate our lives. And like Odysseus, we run the risk of being lured into passivity and inattention until we forget what is important to us, and what truly matters. Sometimes we need a reminder to get us back on course. When Odysseus lodged too long with Circe, his crew had to remind him to resume his journey. For those of us who have lingered too long in the shadow of the Machine, this book serves as a reminder to resume the journey, and a challenge to stay the course in the pilgrimage to our true homeland, namely the renewed cosmos.