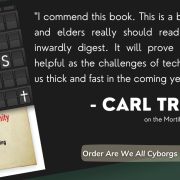

As a foretaste of the material in my forthcoming book We’re All Cyborgs Now: Technology and the Christian Faith, I published an article at The Symbolic World called “Technology and the Story of Redemption: Being the People of God in a Mechanized World.” From the article:

Our world may not feel as mechanical as the days of pneumatic tube systems in office buildings, or giant clocks you could crawl inside. Our technologies have parts that move at the electrical level, largely out of sight unless you happen to live near a giant data center. Yet in a sense our society represents the triumph of mechanism, since the technological turn of mind now encompasses even thought and emotion. Every time I go into the local Barnes & Noble, I am struck by how everything from wellness to anti-aging to wealth accumulation to finding happiness has been reduced to a technique. The subtext is that suffering is only a mistake for those who haven’t discovered the right mechanism. This is the same mechanistic worldview as ANE idolatry: through the right techniques, we can insulate ourselves from the effects of the fall. As with every lie, however, it is based on a grain of truth. In a mechanical age, we are partially mitigated from the impact of death and pain in significant ways, as everything from modern dentistry to antibiotics have helped lessen certain impacts of the fall. The problem arises when we fall into the sin of Cain’s family by using technology to obscure our total dependence on God. In a technological society, we may not feel the need to ask God to send the rain, to keep wild animals at bay, or to provide food. Yet through asceticism, prayer, and spiritual disciplines, we can retrain ourselves to the reality of our total God-dependence. This God-dependence is one of the ways we model how to wisely inhabit a technological society, beyond specific responsible uses of individual tools….

Christians need to get comfortable with the spiritual ambiguity of technology and cities this side of Christ’s Second Coming. Yes, the positive examples of mechanistic innovation are almost endless, from irrigation systems to cooking technologies to all the tools and processes that go into building a cathedral. But technology, like the descriptions of Jerusalem in the Old Testament, is tinged with a deep ambiguity. This ambiguity is present not merely in how we think about mechanism, but also how we behave as practitioners. For example, it is often unclear how to strike the balance between technologies that are restorative vs. technologies that extend man’s power unnaturally and dangerously, or the balance between cultivating and keeping, between tending and subduing. Even restorative technologies are deeply ambiguous as they often insulate us from the consequences of our sin. The ambiguity of technology is seen in the life of Christ Himself. Significantly, the God-man comes to us as a carpenter, which in Greek is tektōn: an ‘artisan’ or ‘skilled worker.’ But, as John Dyer reminds us, ‘The significance of Jesus’s work on earth was not carpentry but what he did through the cross. And yet technology had a part to play in the center of the redemptive story as well. In another strange irony, the technology with which Jesus worked — wood and nails — was the technology on which he died — a cross.’

The cross offers a way to reframe our approach to technology by pointing toward a different relationship with our finitude, vulnerability, and pain. For Cain and Babel, mechanism was an attempt to eradicate the impact of the fall. Cain and his descendants answered the Promethean call to grab technological secrets for achieving power and glory. But as we have seen, the Promethean vision comes at a heavy cost. The heirs of Prometheus are not simply content to use fire to forge iron; rather, contemporary man attempts to create the world in his image and then discovers that he can do so only on the condition of constantly remaking man to fit it. As we accelerate toward technocracy, making man in the image of the machine, we may find that, like Prometheus and Cain, we will be forging chains that will bind us to the consequences of our actions in irreversibly dehumanizing ways. Again, Prometheus’s less-known younger brother, Epimetheus, may hold the answer.

History has not been kind to Epimetheus, who is remembered as one lacking foresight. When the Titan brothers were tasked with giving gifts to all the creatures, Prometheus provided man with the stolen fire, but Epimetheus found he had run out of gifts, having distributed everything first to the animals. As retribution for stealing fire, Zeus gave humanity the woman Pandora, along with her famed box of evils. Yet Pandora, like Eve, is also the harbinger of hope, the one thing that did not escape from the box. While Prometheus strove to master what belonged to the gods, Epimetheus embraced the creaturely finitude by uniting himself to Pandora. Their union becomes an act of hope and love, of grace and rootedness. As such, Epimetheus becomes the progenitor of those who celebrate all those things that make us distinctly human: art, music, literature, craft, cooking, hiking, and leisure (understood in the classical sense).

If Prometheus is the Greek version of the Biblical Cain, who is the biblical type for Epimetheus, who embraced creaturely limits? I suggest that it is Christ. Although the most powerful man ever to live, He never strove to take the primordial fire. He could have called down burning retribution upon his enemies, an action His disciples once urged him to perform, but instead walked the path of the servant. Rather than follow the Promethean example to assert power at all costs, Christ embraced vulnerability even unto death. As such, Christ points the way to a humane way of life. In Christ we learn that our very fragility, vulnerability, and weakness can be the birthplace of connection, beauty, and hope (cf. 2 Cor. 12:9).

Read more at The Symbolic World.