In April 2009, British atheist A.N. Wilson shocked the world by announcing that he was returning to the Christian faith. When asked later in an interview what was the worst thing about being faithless, the writer and newspaper columnist replied:

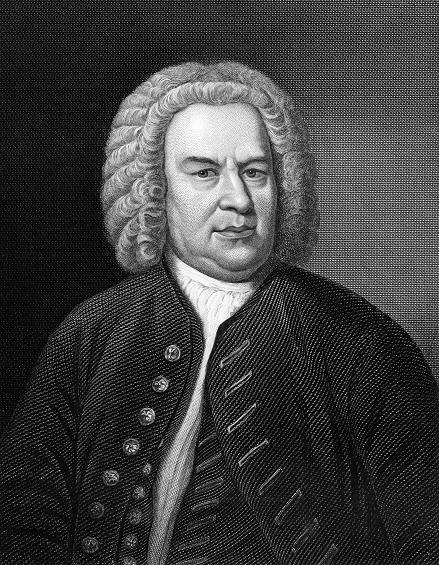

When I thought I was an atheist I would listen to the music of Bach and realize that his perception of life was deeper, wiser, more rounded than my own. . . . The Resurrection, which proclaims that matter and spirit are mysteriously conjoined, is the ultimate key to who we are. It confronts us with an extraordinarily haunting story. J. S. Bach believed the story, and set it to music.

A.N. Wilson is not alone. In his Introduction to the book Does God Exist? Peter Kreeft noted that he personally knows three ex-atheists who were swayed by the argument, “There is the music of Bach, therefore there must be a God.” Of these, Kreeft informed his readers, two are now philosophy professors and one is a monk.

Even the God-hater Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), upon hearing a performance of the St. Matthew Passion, was compelled to admit that “one who has completely forgotten Christianity truly hears it here as gospel.”

Bach would certainly approve, for he once remarked that “music’s only purpose should be the glory of God and the refreshment of the human spirit.” To underscore this point, he wrote the initials SDG (Soli Deo Gloria) at the end of most of his scores.

But who was this man whose music reaches down through time to touch people in such powerful ways? That is the question I have tried to answer in the chapter on Bach in my book Saints and Scoundrels. Writing the chapter was difficult for me because I wanted to encapsulate, in a very short space and in terms that would be intelligible to a non-musical reader, what it is about Bach’s life and music that radiated the gospel. Here is a section from my chapter:

It is impossible in a few words to describe Bach’s musical legacy. His compositions are incredibly varied and defy categorization. From works that reach dizzying heights of mathematical complexity—The Art of Fugue—to lush melodies like his Air on the G String, to works such as the Chromatic Fantasy which approach a jazzy dissonance, his music is of astonishing range and variety. Though his music has sometimes been caricatured as being dry and academic, his compositions actually explore the full range of human emotions from deep sadness (Passacaglia and Fugue for Organ in C Minor) to playful joy (Brandenburg concertos).

But by far Bach’s greatest legacy remains his Sunday morning worship music. “His conscious life-long purpose,” wrote Edward Dickinson in Music in the History of the Western Church, “was to enrich the musical treasury of the Church he loved, to strengthen and signalize every feature of her worship which his genius could reach: and to this lofty aim he devoted an intellectual force and an energy of loyal enthusiasm unsurpassed in the annals of art.”

The theological underpinning behind Bach’s church music was drawn from 1 Chronicles 25 where David and the captains of his army separated out certain individuals for praising God through music. In the marginal notes of his Calov Bible commentary (drawn from Luther’s writings, which Bach used to help him study Scripture), Bach commented that 1 Chronicles 25 formed “the true foundation of all God-pleasing music.” Elsewhere he observed that “at a reverent performance of music, God is always at hand with his gracious presence.”

In Bach’s church music one can feel that gracious presence. This is especially true of the music he composed for the Passion narratives of Matthew and John. The St. Matthew Passion centers mainly on the sacrificial nature of Christ’s death. In this dark, but rich musical setting, the agony of Christ is almost palpable.

Bach’s work with the Passion narratives emerged out of the extreme importance he attached to the finished work of Christ on the cross. It is no coincidence that in his Bible Commentary, Bach underlined Luther’s comments on John 19:30, where the reformer writes that “Christ’s suffering is the fulfillment of Scripture and the accomplishment of the redemption of the human race.” Bach clung to this redemption, which gave him a quiet confidence in God in the midst of life’s many difficulties.

Even though his genius reached the pinnacle of perfection in his church music, Bach is remembered today mainly for his instrumental works. Yet even these compositions preach to us and are a musical expression of Trinitarian dynamism. He was able, like no other composer before or since, to present a number of independent melodies, all unique in themselves, but which weave together to form a single texture that is itself complete without compromising the diversity of the parts.

It is impossible in a few words to describe Bach’s musical legacy. His compositions are incredibly varied and defy categorization. From works that reach dizzying heights of mathematical complexity—The Art of Fugue—to lush melodies like his Air on the G String, to works such as the Chromatic Fantasy which approach a jazzy dissonance, his music is of astonishing range and variety. Though his music has sometimes been caricatured as being dry and academic, his compositions actually explore the full range of human emotions from deep sadness (Passacaglia and Fugue for Organ in C Minor) to playful joy (Brandenburg concertos).

It is impossible in a few words to describe Bach’s musical legacy. His compositions are incredibly varied and defy categorization. From works that reach dizzying heights of mathematical complexity—The Art of Fugue—to lush melodies like his Air on the G String, to works such as the Chromatic Fantasy which approach a jazzy dissonance, his music is of astonishing range and variety. Though his music has sometimes been caricatured as being dry and academic, his compositions actually explore the full range of human emotions from deep sadness (Passacaglia and Fugue for Organ in C Minor) to playful joy (Brandenburg concertos).