It is significant that the desacralisation of time among the Puritans’ descendants resulted, not in a calendar free of liturgical significance, but in time becoming ordered according to the new liturgies of secular nationalism.

Being creatures of time and space, we invariably organize time into rhythmic structures reflecting our common priorities and collective memory. The vacuum created by the evacuation of the church year would come to be filled by those American holidays celebrating civic regeneration, integrating Americans around the liturgies of their common political life.

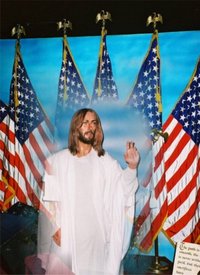

Evangelicals who long ago ceased to tell the story of redemption through the yearly cycle of ecclesiastical holidays became more than comfortable celebrating the birthday of their nation and political leaders with quasi-religious regularity. Evangelicals who would never dream of making the sign of the cross at the end of a prayer became quite comfortable putting their hands on their hearts every morning to say the Pledge of Allegiance with liturgical devotion. In place of the rejected church year, these holidays became public festivals of a new civic order celebrating the achievements of American nationalism.

Spiritual Nationalism and Rationalism

Further understanding of this type of spiritual nationalism was advanced in 2009 when James K.A. Smith came out with Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation, the first volume of a series devoted to cultural liturgies. Smith opening concern is to sketch a certain anthropology that, he believes, will enable us to better grasp the role liturgies play in the formation of the affections. He begins by separating himself from what he calls a “rationalistic” or “cognitive” anthropology which has often functioned as the background narrative to much American Protestantism. By ‘cognitivist anthropology” Smith has in mind a network of practices which treat human identity as primarily cognitive and which assume that what we think fundamentally defines who we are and what we prioritize. Referring to this anthropology, Smith writes,

“While this model of the person as thinking thing assumed different forms throughout modernity (e.g., in Kant, Hegel), this rationalist picture was absorbed particularly by Protestant Christianity (whether liberal or conservative), which tends to operate with an overly cognitivist picture of the human person and thus tends to foster an overly intellectualist account of what it means to be or become a Christian. . . It is just this adoption of a rationalist, cognitivist anthropology that accounts for the shape of so much Protestant worship as a heady affair fixated on messages… The result is a talking-head version of Christianity that is fixated on doctrines and ideas…

“Our worldview is more a matter of the imagination than the intellect, and the imagination runs off the fuel of images that are channeled by the senses…The senses are portals to the heart, and thus the body is a channel to our core dispositions and identity. Over time, rituals and practices – often in tandem with aesthetic phenomena like pictures and stories – mold and shape our precognitive dispositions to the world by training our desires. It’s as if our appendages function as a conduit to our adaptive unconscious: the motions and rhythms of embodied routines train our minds and hearts so that we develop habits – sort of attitudinal reflexes – that make us tend to act in certain ways toward certain ends.”

What does this have to do with spiritual nationalism? Simply this: Smith suggests that the pull of American nationalism has been that its liturgies reach our hearts through our bodies, thus doing justice to our reality as embedded creatures and, in the process, inscribing our hearts with a certain vision of human flourishing. By “the rituals of nationalism” Smith has in mind “certain constellations of rituals, ceremonies, and spaces that…invest certain practices with a charged sense of transcendence that calls for our allegiance and loyalty in a way meant to trump other ultimate loyalties.” Some of the most obvious examples of this are the iconic rituals channeled through the sports/entertainment complex. Referring to these Smith writes that

“These nationalistic and patriotic rituals are intended to make us into certain kinds of people – good, loyal, productive citizens who, when called upon, are willing to make ‘the ultimate sacrifice’ for the good of the nation (under whatever its particular banner might be, whether freedom or the Volk). As I’ve been emphasizing, this formation happens liturgically, not didactically; that is, such rituals grab hold of our desire and our love through our bodies – through material, visceral rhythms, images, and experiences that subtle inscribe in us a desire for other kingdoms. And this isn’t just true of the ‘fabulous’ civic theologies of Rome (as Augustine called them), nor is it restricted to the overt nationalistic rituals of National Socialism or the stark May Day parades of Soviet communism. In some contexts, such liturgies are not necessarily (or primarily) state sponsored; instead, an overarching commitment to the nation or the people so suffuses a national ethos that liturgies and rituals that infuse this are orchestrated by all sorts of nongovernmental institutions…. These material, tactile rituals are formative precisely because they are material – because they get hold of our passions through the body, seeping into our imaginary. Such formation is less the fruit of civics class and more the fruit of repeated rituals – daily (the Pledge of Allegiance in the classroom), weekly (the national anthem at the high school football game), annually (the neighborhood Fourth of July parade) – that present powerful, moving portrayals of an ideal that seeps into our bones…”

Smith goes on to argue that one of the reasons the American church has been vulnerable to these nationalistic rituals is precisely because its own liturgies have been de-materialized through Gnostic assumptions, leading Protestants to work within the narrow confines of a cognitivist anthropology. By contrast the state has remained “sacramental” even as the church has “bought into a kind of Cartesian model of the human person, wrongly assuming that the heady realm of ideas and beliefs is the core of our being.”

It plunks us down in a “worship service, the culmination of which is a forty-five minute didactic sermon, a sort of holy lecture, trying to convince us of the dangers by implanting doctrines and beliefs in our minds. …the (Protestant) church still tends to see us as Cartesian minds. While secular liturgies are after our hearts through our bodies, the church thinks it only has to get into our heads. …While secular liturgies are enticing us with affective images of a good life, the church is trying to convince us otherwise by depositing ideas. …We may have construed worship as a primarily didactic, cognitive affair and thus organized it around a message that fails to reach our embodied hearts, and thus fails to touch our desire.”

By contrast, the liturgies of American nationalism do grab our hearts on the level of our affective unconscious in part because our civic institutions have not succumbed to a Cartesian anthropology.

Civic Redemption Narratives

Undoubtedly the Puritans were animated by noble motives when they rejected the cycle of Christian holidays, for they wanted to show that the entire year was sanctified, that every day is a holiday unto the Lord. However, by relinquishing the church year as one legitimate way to tell the story of redemption, the Puritans and their descendants bequeathed to America a sense that religion is most pure when disembodied, detached from the space-time continuum. This would ultimately reinforce a duality in North American culture that emerged under the Puritan’s canopy, including a false dichotomy between the sacred and the secular.

The elimination of sacred times, like the rejection of sacred spaces, involves a failure to take seriously the reality of incarnation and resurrection; this, in turn, creates a vacuum for other quasi-religious metanarratives to be incarnated in a people’s social imaginary. Being creatures of time and space, any attempt to disassociate the gospel from its embedded-ness in time and space opens the material realm up to various forms of pseudo-religious ordering.

One of these quasi-religious metanarratives is the idea of civic soteriology. The redemptive motif in America’s founding, and the implicit soteriology behind it, is shared on all sides of the political spectrum. Those on the political right tend to emphasize the relationship between America’s founding with certain notions of individualism and liberty, while those on the political left tend to emphasize the relationship between America’s founding with certain notions of equality. Both groups tell the story of American democracy as their own, a redemptive narrative that includes a significant element of forward-looking eschatology. This was illustrated in Barack Obama’s acceptance speech in Chicago on November 5, 2008 where he told the story of American history, from its inception to its growth into civic maturity in a “new dawn of American leadership” – a process that climaxes in his own utopian announcement: “Our union can be perfected.”

These redemption motifs are reinforced by the type of material rituals that have come to underlie the very fabric of civic life and which charge the state with an implicit transcendence, investing its institutions with a sacral transfiguration. Propelled by a type of implicit soteriology that idealizes America’s founding, many evangelicals have begun investing the principles behind that founding with the potential for eventually ushering in the civic parousia. Again, one only has to read Marshall and Manuel’s The Light and the Glory (the American Christian’s version of what Virgil’s Aeneid was to the Romans) to get a flavor of what I mean.

To read more about the importance of the church year, see the two-part series I wrote in 2011 for the Reformed Liturgical Institute at the links below. In Part Two of this series I develop a case that a robust affirmation of, and participation in, the ecclesiastical calendar can act as an effective hedge against the types of statist idolatries discussed in this post: