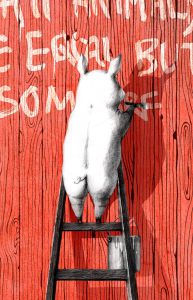

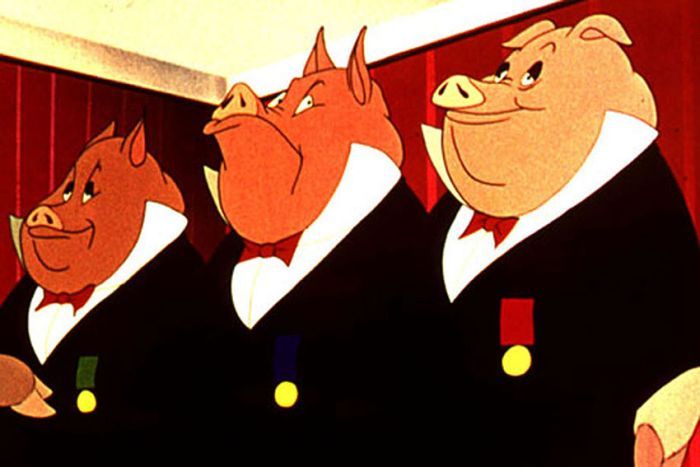

Animal Farm is a uniquely human story. Even a cursory glance over the last half millennia reveals that empowerment has a strange way of enticing former liberators not merely to abandon their own principles, but to begin embodying the principles of their opponents.

We saw this happen when the “Committee of Public Safety” abandoned the principles of the French Revolution, ushering in a terror far worse than anything under the Ancien Régime. We saw it again when the Soviet State abandoned the pseudo-liberating rhetoric of Marxism and turned all of Russia into a giant prison. We saw it again when the “agrarian socialism” of the Khmer Rouge found embodiment in the genocide of Pol Pot.

The pattern should now be a well-established maxim of history: when revolutionary movements come to power, it is typical to find the revolutionaries abandoning their principles and assuming the ideologies of their adversaries while still clinging to their movement’s original rhetoric. As Lord Acton famously put it, “Power tends to corrupt; absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

The most recent instance of this type of ideological reversal is the strange evolution happening in the Republican Party since their ascendancy to executive power a little over a year ago. In a surreal move that has gone almost entirely unnoticed, the Republican Party began quietly adopting a political philosophy that used to be the sole province of their liberal opponents: namely, identity politics.

In identity politics, one’s particular group forms a lens through which to view political issues or to make policy decisions. Identity politics is strongly anchored in a type of cultural Marxism in which a person’s group becomes the nexus of personal and social identity. Identity politics eschews the type of color-blind state that early civil rights activists strove to achieve, since the advancement of my group—whether black, Hispanic, lesbian, feminist, blue collar worker, single moms, native American—becomes the defining feature of my political identity and the criteria to which all political principles become subservient.

Identity politics is not primarily about one’s position on specific issues; rather, it is the animating philosophy behind one’s position on particular issues. This includes a group-based political philosophy that is emboldened by a narrative of victimhood and an inflammation of grievances. Closely aligned with a postmodern denial of any normative moral framework, identity politics collapses public discourse into mere competition for power. In a world where there is no recognition of a normative framework that might provide for objective appeals to the common good, all that remains are appeals to raw power based on what will benefit specific groups. (I discuss this in more detail in my article “2016 and the Triumph of Nominalism.”) Facts, rationality and objective truth become subservient to posturing, manipulation, and the strategic use of confusion to befuddle one’s opponents. In identity politics, discourse becomes a means to assert dominance.

Though identity politics is in tension with the values of classical liberalism, in many ways it is also its natural correlate. Historically, nations are held together by common memories, customs, symbols, myths and legends. In its most rigorous and consistent form, classical liberalism de-emphasizes or ignores these deep-seated cultural-symbolic underpinnings of civil society and attempts to secularize the public life, often migrating transcendence to the claims of the state. This creates a dangerous vacuum in which citizens find themselves without the basic building blocks of national cohesion. This inevitably results in human beings looking to their most basic and primitive bonds for cohesion, and thus reverting to a raw tribalism. A secular and materialistic society offers little scope for the type of roots that humans innately long for, with the result that the most plausible roots become race and ethnicity.

Obama did not cause this state of affairs, to be sure, and in many ways he was a symptom of a type of cultural neo-Marxism that had its genesis in figures like Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937) and schools of thought like the Frankfurt Movement (for more about that, see my book Saints and Scoundrels, chapter 16).

In many ways, the situation in America came to be akin to the state of affairs prior to the Civil War. In the antebellum period, the problem wasn’t simply the intractability of two opposing positions, each of which claimed to represent the true legacy of America’s founding; rather, the problem was the mutual incomprehensibility that arose from a complete breakdown of attentive communication. The resulting problems could only be solved through raw power, leading to the deadliest war in American history.

As identity politics has fractured America into various ideological tribes, we could be fast approaching a state of affairs very similar to America during the antebellum period. Consider that on both the Left and the Right, people are beginning to speak of their political opponents with contempt, employing a rhetoric of contempt previously reserved for traitors or groups with whom one is preparing to wage war.

In our fractured and divided nation, it shouldn’t have taken a great deal of sagacity to know that what America needed was a leader who could bring people together; a leader who could put the breaks on tribalism to show that what we have in common as Americans is at least as important as our differences.

Given the Republican Party’s historic opposition to the identity politics, one might be forgiven for expecting the Republicans to provide such a candidate.

Enter candidate Trump.

If the rise of Identity Politics under Obama had led us to suppose that it was impossible for different groups to communicate across the ideological divide, President Trump has not left us with any doubt. From his intentionally incendiary rhetoric to his use of Twitter to insult various groups and people, one would be forgiven for thinking that his number one aim has been to continue Obama’s legacy of widening our nation’s social polarizations. This, of course, is a key feature of identity politics, where a group-based narrative of victimhood feeds on division against other groups and can really only be sustained in a climate of division. Moreover, President Trump’s frequent appeals to a Nietzschean “might makes right” philosophy, leaves one wondering if his goal is to completely remove public discourse from any rational footing to make it a zero-sum game between winners and losers. This again is integral to the neo-Marxism that undergirds identity politics, for in the absence of a normative framework that might provide objective appeals to the common good, all that remains are appeals to raw power based on what will benefit specific groups. Or again, the functional relativism of Trump and his supporters coheres like a hand and glove with the basic ideological coordinates that have always animated identity politics with its strong roots in postmodern epistemology. Under President Trump, a new type of conservative politics is emerging that eschews the political skills, such as consensus building and professionalism, in favor of a rhetoric of contempt and the use of politics to assert dominance.

When I think of the new right-wing identity politics, I think of a friend at work named Aaron. Aaron considers himself hyper-conservative, yet unabashedly advocates identity politics. He denies that there is any such thing as a common good, but maintains that each group inevitably fights for what is best for them in an inescapable struggle for dominance. Believing that there is no objective framework that can adjudicate disputes, Aaron maintains that we are left to settle our differences by force and power. He is an avid supporter of President Trump, and wishes that the President would suspend democracy to rule as a military leader. Aaron is extreme, but how many “moderate” Republicans have now drunk the poison Kool-Aid of social Marxism, with its assumption that there because there is no normative framework that might provide for objective appeals to the common good, all we are left with is appeals to raw power based on what will benefit specific groups.

The conservatives who have embraced identity politics under Trump are not bad people and are not necessarily racist, just as the ethnic minorities who embraced identity politics under Obama are not necessarily bad or racist. But one of the problems with identity politics—whether from the Right or the Left—is that whenever it is allowed to flourish, it foments and encourages the worst elements of our society, including those who are willing to use violence to suppress the groups they dislike. When this happens, people in the middle easily drift to the extremes, being emboldened by those on the other extreme in a toxic spiral of self-perpetuating reactions and counter-reactions.

I see these very dynamics being played out in my own community since Trump’s ascendancy to power. A few weeks ago, a friend of Jewish ancestry told me how alarmed he was when, about a year ago, his Facebook feed began regularly to be flooded with pictures of the swastika and inflammatory rhetoric about needing to drive the Jews out of America. The other day, I was shocked when someone announced to me that Hitler was actually “a good leader” and had to send Jews to camps in order to protect the Germans from their influence. Someone else who claimed to be conservative informed me that the holocaust never happened and went to great pains to list for me all the good things Hitler had done. These examples could be multiplied endlessly, but what is even more alarming is that explicit race-based supremacy narratives are even becoming a feature of mainline conservative journalism, as evidenced by recent concern about Pat Buchanan’s comments on white supremacy. Towards the end of his controversial article on America’s supremacist origins, Buchanan associates the repudiation of America’s racist origins with liberal economic and social policies he disputes, such as economic redistribution and unscientific ideological sand piles.

While reflecting on these troubling developments this morning, I was startled by the news of Arthur Jones’ unchallenged bid for the Republican nomination in one of Illinois’ congressional districts. Jones, a Holocaust denier with strong ties to neo-Nazi groups, has been unashamedly promoting white supremacy from the platform of an alt-right type identity politics.

Of course, the Republican establishment condemns people like Jones. But are they willing to condemn the tribalism and identity politics that sustains him? In the age of Trump, the answer to this question is no longer clear. The Republican Party seems perfectly willing to use identity politics for their own ends, without any consideration of the larger implications of this dangerous ideological retreat. This is consistent with the type of “might makes right” approach that Trump has been championing and which I discussed in my article “Trump’s Brave New World.‘

Ultimately, however, concern about the new Republican identity politics is not primarily rooted in the fact that alt-right racists are increasingly feeling like they have a home in the Party, as alarming as that should be; nor does it hinge on having to maintain that Trump is an actual racist. We might endlessly debate whether Trump has said or tweeted things that make him a white supremacist or a racist. In many ways, such questions distract from the real issue, which is that Trump’s operational philosophy correlates with key ideological coordinates of identity politics in the ways mentioned above (especially in the above paragraph beginning “If the rise of Identity Politics”). The Democrats cannot offer a critique of this without implicating themselves, since they have been in bed with identity politics for decades; so, sensing that something is wrong, all they can do is try to pin the charge of racism on the President.

Further Reading

- Trump’s Brave New World

- The Non-Conservative Mind of Donald Trump

- Conservatism in Historical Perspectives

- How to Discuss Politics Without Alienating Your Friends in 5 Steps

- 2016 and the Triumph of Nominalism

- Identity Politics

- The “Quiet Revolution” of Cultural Marxism

- The True Meaning of Conservatism