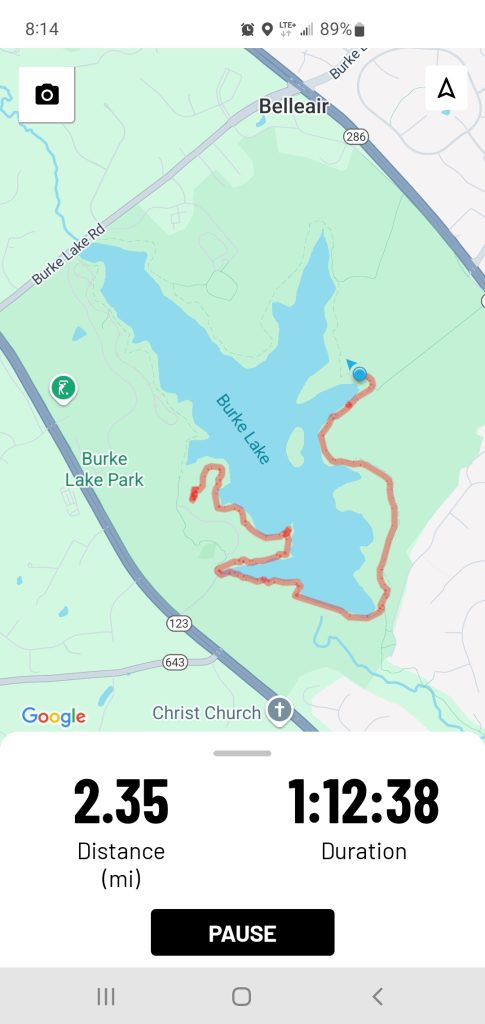

On Saturday I went to explore a new hike with a new book.

On Saturday I went to explore a new hike with a new book.

The hike was the Bull Run-Occoquan Trail (pictured right). The book was N.T. Wright’s new publication The Challenge of Acts: Rediscovering What the Church Was and Is.

This was a particularly joyful morning for me. One of the difficulties of moving to the Manassas/Centreville area last July is that I ceased having the same easy access to the Appalachian Trail as when I lived in Culpeper. So discovering this 17-mile hike only 20 minutes from my house was a joy.

The morning was a double-joy because of getting back into N.T. Wright after a few years’ break from reading the Anglican theologian. Wright’s work had a profound impact on me when I was part of a Gnostic sect in the UK, as the Lord used his teaching to help move me out of heresy into the light of biblical truth (a story I tell in my book Rediscovering the Goodness of Creation: A Manual for Recovering Gnostics). As I walked along the trail, I remembered the debt of gratitude I owe Wright, and how grateful I will always be for his clear exposition of the scriptures.

I didn’t go all 17 miles, but took my time, slowly drinking in the excitement of unfamiliarity that I always feel on a new hike, not knowing what will be around the next turn. I like the familiar hikes, which become like old friends, but there is a particular joy of going somewhere new. Full of scenes from my reading, I find myself half expecting to turn a bend and find a desecrated castle, a woodcutter cottage, or an enchanted part of the forest. And I think that on Saturday there was something enchanting about the forest.

As I read and walked, I wanted to jump up and down and shout for joy, because Wright’s reflections on Acts 1 is so good, offering years of his mature thinking about the kingdom distilled into a very concentrated form (though entirely readable, as this is not an academic book). For me, it helped connect a lot of the dots, especially about the theology of ascension, what the kingdom of God means for us now, straddled as we are between the inauguration of consummation of Christ’s kingdom.

Theology is probably not something that most of us think of as exciting, as something you would want to jump up and down about while exclaiming “Alleluia!” But that could be because most of us, when we think about theology, don’t think about biblical theology. Accordingly, I want to use this blog post as an opportunity to define biblical theology and explain its importance, as well as situating it in relation to other types of theology.

Once while I was talking with the theologian N.T. Wright at a conference, he shared that when he worked in London, he always used the subway, or the “underground” as it’s referred to over there. Wherever he might surface in London—whether King’s Cross, Covent Garden, or Russell Square—these were isolated destinations that he didn’t understand in relation to the larger topography of the city. But then he got a car and started driving, as well as walking around bits of London. Then he began to perceive the relation between the various areas that had previously merely been stopping points.

Wright told me that this is like studying scripture. Often we dip into isolated events in the Bible, this or that doctrine or passage, without understanding how all of the interconnected pieces fit together into the larger whole. Wright’s overall point is an important one: as useful as it is to study specific passages of scripture, or even whole books of the Bible, we will always fall short of a full understanding if we do not grasp the scriptural story as an integrated whole.

That overarching story is called the redemptive-historical narrative. Essentially, it’s the story of our salvation. The study of that story is called biblical theology.

Maybe you didn’t know that your salvation had a story, or perhaps you’ve thought of your salvation story as beginning with your baptism, or maybe the time you invited Jesus into your heart. But, in point of fact, your salvation story predates you by centuries, even millenniums. The story of your salvation includes the faithfulness of all the men and women who went before – the people who made it possible for you to be a child of God today: men and women like Noah, Abraham and Sarah, Moses, David, John the Baptist, the Blessed Virgin Mary, and so on. The story of your salvation also includes all the post-biblical saints, missionaries and men and women of God who were instruments through which Christianity was brought to your culture (or to the culture of those who shared the gospel with you).

Without understanding this pedigree, we cannot fully appreciate and enjoy God’s work in our lives. This is true of any good story. For example, in the book The Wind in the Willows, it would be difficult to fully appreciate the final chapter when the four friends recapture Toad Hall without first journeying with the characters in the earlier chapters of the book.

The purpose of biblical theology is to connect us to this larger salvation story, and to help us understand how all the pieces of the biblical story fit together. This, in turn, sheds light on things Christians do that might otherwise seem random. Why, for example, do Christians celebrate some Old Testament feasts, such as Pentecost (known in the Old Testament as the “feast of weeks”), but not others, such as Passover? Why do Christians speak of Jesus as the Lamb of God, or refer to the Church as the Bride of Christ? To answer these and similar questions we need to understand the full scope of salvation history as it has unfolded in the redemptive-historical narrative. That is where biblical theology comes in.

Biblical theology is certainly not the only legitimate way of doing theology, but it is a valuable method for helping us grasp the big picture and to understand the progressive revelation of God through the various epochs of history (past, present, and future).

That isn’t always how I understood the Bible. I grew up around Bibles and Christian books because my father was a Bible bookstore owner, in addition to being a Christian author, editor, and publisher. But although I was steeped in the Bible from as early as I can remember, I never really enjoyed reading scripture, apart from the gospels. For me, reading the Bible was a type of “eat your greens” activity that I did out of duty.

The problem, of course, is that I was not reading the Bible as a story; instead I was reading it as a collection of isolated proof-texts or individual stories with little or no relation to each other, like Wright when he surfaced in London but didn’t know where he was in relation to the larger whole. Although I loved stories, but for me the Bible was not a story. I had no understanding of how scripture formed an integrated whole showing the outworking of God’s plan for the earth. Nor did I understand how the New Testament related to the Old, let alone how my own life fit within the narrative of redemption history. Although I could identify specific stories within the pages of Scripture (David and Goliath, Daniel in the lion’s den, Christ’s healing of the paralytic, etc.) I did not understand how these stories fit within the overarching story of God’s plan to redeem humanity and renew the cosmos.

The Old Testament was particularly difficult. Like so many, I tended to approach the Old Testament as a collection of moral examples. For example, when I read about Joshua defeating the Philistines, I took that as an exhortation to fight against the demons that tempt me to sin; when I read the commands in Leviticus about the Israelites avoiding anything unclean, I took that to be a reminder to avoid worldly objects like violent television shows or aggressive rock music. Of course, the problem with seeing the Old Testament as a collection of moral examples is that many of the stories in the Old Testament are actually quite immoral. If, on the other hand, we understand the stories of the Old Testament—occurring, to be sure, in an earlier stage of spiritual and cultural maturity—as part of God’s larger work of redeeming the world, they find a far richer and less troubling place in the narrative than when approached merely as moral examples.

When, in my early twenties, I went to Fairwood Bible college in New Hampshire, the teachers continually reminded us that they were not interested in giving us theological training, but in helping us glean insights from the bible that could apply to our life. That anti-intellectualism sounded very pious, yet without biblical theology it became impossible to grasp how the different parts of scripture’s story (creation, fall, kingdom, exile, redemption, continuation, culmination) fit together in God’s purpose for the earth, let alone appreciate the role God calls us to play within that story. At best, this left us with a very compartmentalized approach to the world, where we had a spiritual history and a secular history running parallel to each other, and sometimes intersecting, but basically proceeding on two different axes and moving toward two separate ends.

I first began to understand the Bible as an integrated whole in the late 90’s after reading an article written by T.M. Moore, who later became my editor when I wrote for the Colson Center. I cannot find the article now, but I remember Moore showing that the Bible is the continuous story of God calling His people, and the cosmos itself, into the experience of kingdom life. That was the beginning of my journey to understand scripture from a new lens, what we might call the biblical theology lens. As I sought out pastors and theologians who taught scripture with a biblical theology lens, they helped me further understand that the story of God’s kingdom is also the story of the whole world. World history is not culminating in the destruction of the space-time universe, as some Christians erroneously teacher; rather, scripture offers the story of the world’s redemption and healing. But this story can be muted if we only view scripture in isolated bits, as I had done for my early life.

I have found that not everyone shares my enthusiasm for biblical theology, even within my own tradition of Eastern Orthodoxy. Though we have some excellent teachers who take a biblical theology approach—I am thinking particularly about Seraphim Hamilton, Fr. Stephen De Young, Fr. Lawrence Farley—this can be particularly muted within catechesis. Throughout the years I have visited a lot of catechism classes in my church, designed for people coming into our tradition for the first time. In most cases I found that biblical literacy was taken for granted rather than taught, with instructors leaping straight into dogmatic theology (a term I will define shortly). There is nothing necessarily wrong in assuming biblical literacy, especially when catechesis usually addresses people who already have, if not a Christian background, at least nominal Christian understanding. Maybe that’s because of living in a Christian nation. But this Christian background can no longer be taken for granted in 21st century America. Increasingly people are walking into the doors of the church with no Christian background at all, while even believers may have only a cursory understanding of scripture. Yet our catechism classes have largely failed to accommodate this reality, but still use models appropriate for the Baby Boomers and Generation X.

In my own tradition, this failure of catechesis is often propelled by ideological antipathy to biblical theology. This came up when I was researching Part 3 and 4 of my book on creation (which offers a summary of the story of salvation from the Old Testament to the present), for as I entered into dialogue with the wider Orthodox community about the redemptive historical narrative, I was surprised how much pushback there was against the redemptive-historical method. One well-known and influential priest/teacher disputed my claim that “new creation theology” (a centerpiece of the redemptive-historical narrative) is even a real thing in our tradition. And if new creation theology isn’t a real thing, then this plays nicely into the neo-epicureanism of people like Fr. John Romanides and Fr. Peter Heers whose metaphysics make God distant form the natural world (a point I discuss elsewhere).

Another reason many catechetical models neglect biblical theology is because of a misunderstanding of what Holy Scripture truly is. Too often we front-load students with doctrines, operating under the unspoken assumption that while these doctrines may have originally emerged from the biblical-historical narrative, the latter served merely as a temporary vehicle for the former. According to this way of thinking, once we’ve extracted what the biblical narratives “really means,” then biblical theology can be folded into systematic theology and we can, so to speak, discard the husk to get at the kernel within, namely a set of abstract doctrines. The redemptive-historical narrative is thus reduced to a kind of puzzle we must decode to find out what God really meant. On this scheme, a passage like Psalm 139:9 (“If I take the wings of the morning and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea, even there your hand shall lead me”) is just another way of affirming the doctrine of God’s omnipresence. Psalm 107:23-24 (“they that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters; they have seen the works of the Lord and His wonders in the deep”) is just a more decorative way of stating the doctrine of intelligent design. This approach treats the rich imagery in these and other passages as simply a delivery mechanism for some other supposedly more “real” meaning. The same rationalism also renders the historical-redemptive a mere vehicle for a set of abstract doctrines. The long and checkered history of God’s people from the Patriarchs through to the prophecies of John the Baptist is fundamentally a doctrinal delivery system; consequently, once we have extracted the key doctrines, the redemptive-historical narrative need not overly concern us. But this is a massive misunderstanding of what Holy Scripture is. Just as the imagery in passages like Ps 107 and 139 is not simply a vehicle for the real point since the imagery is the point, so the redemptive-historical narrative is not simply in instrument for conveying doctrines (even the doctrine “God is redeeming the world”); rather, the story is the point.

The reason the story is the point is because you and I are living within that story. But to understand our place in that story, we need to immerse ourselves in that story, including what we know of the past parts of the story as well as the future, still unfilled, parts that we call eschatology. That is the purpose of biblical theology.

I think at this point it will be helpful to define biblical theology in relation to other types of theology so we can see how it compliments and contrasts other theological modes with which we may be more familiar.

Different Methods of Theology

The French impressionist painter, Claude Monet (1840–1926), loved water lilies. The centerpiece of his garden at his home in Giverny was the waterlily pond. He imported exotic varieties of water lilies and painted them from numerous angles and at different times of day. Monet understood that there was not just one way to look at water lilies, because even a single water lily could be viewed from multiple directions, in various seasons, and at various times of day. Altogether, his corpus of water lily paintings totals 250, with each one offering an understanding of water lilies that is slightly unique, highlighting different features of these remarkable plants. The different perspectives of waterlilies don’t contradict each other; on the contrary, because water lilies are so beautiful and multifaceted, it is impossible to capture their complexity without multiple perspectives.

Theology is like water lilies. When we love Christ, we want to understand Him in as many ways as possible, just like Monet used a variety of techniques and perspectives to view water lilies. For us, that means viewing theological truth from many different perspectives, using a variety of methods and theological tools.

Let’s consider some of these different theological methods now. This, in turn, will help us define and appreciate biblical theology as a distinctive way of studying theology. But at the outset I want to be clear that the distinctions between these methods are porous and, in some cases, somewhat artificial. All types of theology, when pursued properly, cross-fertilize each other.

Systematic Theology

Systematic theology is the branch of theology that attempts to articulate the doctrines of the Christian faith in a rational manner, and to offer an organized and comprehensive understanding of the Christian faith. For example, systematic theology deals with

- the doctrine of God (Trinitarian theology)

- the doctrine of Christ (Christology)

- the doctrine of salvation (soteriology)

- the doctrine of the church (ecclesiology)

- the doctrine of the Holy Spirit (pneumatology)

- the doctrine of last things (eschatology)

Issues of systematic theology might include questions like the following:

- How can God be both one and three?

- What is the role of the Holy Spirit in redemption?

- What is original sin, and how does it affect human nature?

- What is the relationship between the universal Church and local congregations?

- What happens to the believer at baptism?

- What is the relationship between faith and works in salvation?

Dogmatic Theology

Dogmatic theology is related to systematic theology and, in fact, the two are often used interchangeably. However, in a precise sense, dogmatic theology refers to the study of the official teachings of a specific communion – the creeds, catechisms and teachings (in short, the dogmas) of particular Christian communities, whether Catholics, Lutherans, Methodists, Mennonites, Pentecostals, Presbyterian, Orthodox, Baptist, etc.

If you were studying the Eucharist from the lens of dogmatic theology, you might explore the Roman Catholic view of Transubstantiation, or the Lutheran view of Consubstantiation, or Zwinglian and modern evangelical view of Memorialism, and so forth.

Practical Theology

Whereas systematic theology and dogmatic theology deal with how to think about the doctrines of the Christian faith, practical theology deals with how to live and apply the faith to various issues. This might include subdisciplines such as eco-theology (using theological resources to clarify our responsibility to care for the natural environment), or political theology (using theological resources to think about government and state), or liturgical theology (exploring the theological significance of worship and liturgy), or liberation theology (exploring theology in light of social justice and God’s liberation of the oppressed), etc.

The main subset of practical theology is pastoral theology. Often when people refer to “practical theology” they simply mean pastoral theology. Related to ethics, pastoral theology explores the applied aspects of Christian faith, often in the context of equipping pastors for church ministry. Pastoral theology is often issues-based, leveraging theological resources for dealing with practical problems like addiction, depression, climate change, globalism, etc.

Pastoral theology looks at the tools needed for the care of souls, including resources from counseling and psychology. For example, if you were studying the Eucharist from the lens of pastoral theology, you might explore how Holy Communion functions as a resource for healing, or how the Lord’s Super relates to church discipline, etc.

Historical Theology

Historical theology is the study of the development of Christian theology, including the history of Christian doctrine, or the thought of specific theologians or schools of thought.

If you were studying the doctrine of providence in the work of John Calvin, or the ecclesiology of St. Cyprian of Carthage, or St. Gregory the Great’s theory of pastoral care, this would come under the category of historical theology.

As you might have guessed from the above examples, historical theology has considerable overlap with other types of theology. But while historical theology overlaps with systematic, dogmatic and practical theology, it also challenges these very distinctions. Historical theologians point out that the division of theology into these various subdisciplines is of comparatively modern origin, because for most of human history, dogma, morals, the study of scripture, and the care of souls, etc. were discussed as an integrated whole.

Philosophical Theology

Whereas historical theology uses the tools of history to draw theological inferences, philosophical theology uses the tools and methods of philosophy to understand theological truths. Philosophical theology deals with

- questions of theodicy (e.g., is the goodness of God rational in light of evil?)

- questions of epistemology (e.g., is there conflict between faith and reason?)

- questions about the nature of God (e.g., divine simplicity, omniscience, timelessness, impassability)

- questions of providence (e.g., what is the relationship between divine foreknowledge and human free will?)

- questions of language (e.g. how can a finite creature speak meaningfully about the infinite God?)

- questions of morality (e.g., is an action good because God wills it, or does God will the action because it is good?)

This list might go on, but I’m sure you’ve grasped the nature of philosophical theology.

To return to the Eucharist, if a philosophical theologian was exploring this topic, he or she might ask questions such as, “how does the concept of sacramental presence compare to other types of presence (e.g., spatial, personal, or spiritual)?” or “Can we use Aristotelian categories to explain what happens with the bread and wine become God?”

Exegetical Theology

While all types of Christian theology are ultimately rooted in scripture, exegetical theology is the specific branch of theology concerned with the careful analysis and interpretation of the Bible. There are a variety of methods for doing exegetical theology, ranging from the grammatical-historical method to literary analysis to source criticism. But at the core of exegetical theology is the question, “What does this text mean?” To answer this question, exegetical theology offers numerous tools, including literary structure analysis, textual criticism, and the study of biblical languages.

If we were to return to the question of the Eucharist, while someone doing historical theology would ask, “What was St. John Chrysostom’s teaching on the Eucharist?” and someone doing dogmatic theology would ask, “What is the position of this-or-that church on the doctrine of the Lord’s Supper,” someone doing exegetical theology would analyze the actual language of John 6:53 or Matthew 26:26-30.

Biblical Theology

Having gone through this survey of different types of theology, we are in a position better to understand biblical theology. Although I defined it previously, there may still be some confusion because of the term “biblical.” Often use “biblical” as an adjective denoting “according to the Bible,” faithful to scripture, the opposite of unbiblical. But this is not the meaning of “biblical” here. Biblical theology does not refer to theology that is not unbiblical; rather, it is a specific way of doing theology that contrasts—though compliments—the methods discussed above. As already mentioned, biblical theology is the study of salvation history, as outworked within the redemptive-historical drama of scripture.

In the simplest terms, biblical theology is the study of salvation history, as outworked within the redemptive-historical narrative of scripture. Whereas exegetical theology focuses on specific verses, biblical theology looks at the big picture themes of scripture over time. That said, biblical theology can be understood as a subset of exegetical theology since it is ultimately concerned with the interpretation of scripture, which is to say, “what does the text mean?” A well-trained exegete will be attentive to the larger redemptive-historical context surrounding the verses he is analyzing, while someone operating in biblical theology mode will never leave behind the tools for carefully exegeting relevant passages. Thus, biblical theology shares in common many of the tools of exegetical theology, such as historical context, intertextuality, imagery, typology, symbolism, and allegory. Don’t worry right now about understanding what all those words mean. The main thing to understand is that what sets biblical theology apart from general exegetical theology is its specific object of inquiry, which is the story of redemption. As such, biblical theology looks at the historical and literary contexts of scripture in order better to understand the world’s redemption as outworked in the progressive development of themes and ideas throughout the various epochs of covenant history, such as creation, fall, election, kingdom, exile, incarnation, church, culmination, and eschaton.

Here are some typical questions biblical theology seeks to address:

- How is symbolism from the Garden of Eden incorporated into David’s temple, and what is the significance of that in terms of the larger redemptive-historical narrative?

- How does the covenant with David build on and fulfil God’s covenant with Moses?

- How is speaking in tongues at Pentecost (Acts 2:1–11) a reversal of the confusion of tongues at the Tower of Babel (Gen. 11:1–9)?

- How is the Creator God working to heal the cosmos, and what does this tell us about the future of our planet?

- How do the hopes in the prophetic corpus (that God would forgive His people, that the divine presence would return, that there will be a Second Exodus, and that God will heal the earth) find fulfilment in Christ?

This last question is crucial. In recent years there has been a recovery of the ancient understanding that the redemption of mankind is linked to the redemption of the entire cosmos (see my book Rediscovering the Goodness of Creation: A Manual for Recovering Gnostics), and so increasingly theologians will want to link biblical theology to the story of the redemption of the cosmos, as indeed I have done even in how I define biblical theology.

So how does biblical theology work in practice? Let’s go back to a question like the Eucharist. If we were considering the Eucharist from the perspective of biblical theology, we might explore how the original Passover prefigures the Eucharist, or how Christ’s identification with the “bread of life” (John 6:35) evokes manna symbolism, thus underscoring His ministry in bringing about the long-awaited Second Exodus.

Or take another example, the problem of evil. A systematic theologian, perhaps aided by tools from exegetical theology, might pick up some of the debates about certain passages (e.g., Romans 9) which suggest that evil arises from God’s providence; and he might go on and ask what this means for the doctrine of God’s goodness. But if we were exploring evil using the tools of philosophical theology, we might consider how God can be all-good, all-wise, and all-knowing yet still allow evil to exist. Or within pastoral theology, one might consider evil as a pastoral problem, while exploring what resources the church has for breaking generational trauma caused by past evil. All these are crucially important, to be sure, but biblical theology looks at it from a different angle, asking: what is the story of how God is dealing with evil throughout the course of world history? That, of course, takes us to the space-time world of biblical history: to actual people like Abrham, Moses, David, John the Baptist, the Blessed Virgin, who were all part of God’s plan for dealing with evil. These figures, of course, culminate in Christ, whose life-giving death and resurrection dealt a blow to the powers of darkness. Thus, the solution to evil afforded by biblical theology turns out to be not an argument or a dogma, but a Person within space-time. But also, biblical theology must confront the fact that even after Christ’s triumphant defeat of the dark powers, evil continues to exist. Thus, at the heart of biblical theology is the quest to understand our own place within the story of redemption history, as we live straddled between the inauguration and culmination of Christ’s kingdom.

Given the space-time emphasis of biblical theology, a chief interpretative frame will be historical context, particularly asking,

- how would the original writers and readers of scripture have understood these texts?

- how does the answer to this last question shed light on the story of God’s progressive healing of the cosmos?

These questions position history at the center of biblical theology. Unlike historical theology, which traces the development of Christian thought through the centuries, biblical theology focuses on the historical context in which the Bible was originally written and understood in order to offer a clearer idea of the storyline running through the texts. That storyline, which interconnects all the stories from Noah’s flood to the Virgin’s birth, is the story of the world’s salvation. That story includes you and me, to be sure, yet because humans are a microcosm of the cosmos, our salvation is linked to the restoration of the universe itself. As St. Ephrem the Syrian observed in the fourth century,

When all creatures are joined in love to the Son by whom they were created, and the Son is joined in the love of the Father from whom He was begotten, then, at last, all Creation will confess the Son through whom it has received all blessings. And in Him and with Hm, it shall also confess His father who distributes all riches to us from His treasury.

Not all Christians believe that God is interested in healing the world. As I discussed in my aforementioned book, Rediscovering the Goodness of Creation: A Manual for Recovering Gnostics, some Christian traditions advocate that God will destroy rather than renew the earth; that the world is destined for the cosmic garbage heap. At the risk of oversimplification, Christians holding such views will often conceive salvation in individualistic terms, so that redemption history ceases to be about the healing of the cosmos but simply the story of pedestrian individual souls being saved and rescued out of the world. For Christians holding such views, the “redemptive-historical” narrative is an anachronism: there is a redemptive narrative and an historical narrative, but they tend in opposite directions.

I have found—not surprisingly—that Christians holding that perspective tend to be less interested in biblical theology, just as Christians who espouse anti-intellectualism will be less interested in systematic and philosophical theology, or groups maintaining that the great apostasy theory (i.e., that all of mainstream Christianity has fallen away from the true faith) will be disinterested in historical theology or dogmatic theology. Thus, historical theology is not value-neutral but assumes that there is a redemptive-historical narrative pointing toward the healing of the cosmos.

I want to be clear that biblical theology should never be a one-man show that neglects insights from other methods. For example, to try to do biblical theology without historical theology might lead to neglect of key insights of church fathers and saints, whose work and lives shed insight on the redemptive-historical narrative. Similarly, a biblical theology that doesn’t translate into mission and parish life (in other words, practical theology) runs the risk of remaining detached and abstract.

Seven Reasons Biblical Theology is Important

But why is biblical theology important? Aren’t the other types of theology sufficient? Certainly no approach to theology should be siloed, as each method of doing theology works best when it draws from and informs other approaches. Remember the analogy of Monet’s water lilies: observing these flowers from multiple perspectives offered Monet (and the viewers of his paintings) an idea of these flowers. So what are the rich perspectives that biblical theology offers, and why is that important? Here are five answers to that question.

Reason #1: Biblical Theology Helps Us Not Get Lost in Irrelevant Details

Because my father owned a Christian bookstore, I interacted with people from many different churches who would meet in the story to discuss issues. I even started a discussion group so I could invite people I met at the store back to the house to discuss a controversial issue. Sometimes the discussions got heated. Once a person left the house angry over a point of theological epistemology.

It was an intellectually vibrant environment, where I was exposed to a variety of different theological viewpoints. For me, this was intellectually enriching and propelled me to study theology further, especially philosophical theology. But I can also understand who sometime might find the variety of viewpoints confusing and intellectually stultifying. Sometimes I felt like that, and for a few years I even wondered if it’s possible to know anything, even the existence of God.

I have talked to others and I know some people find studying the Bible confusing because of all the intra-church controversies that seemingly surround it. Because there are so many different ways of interpreting scripture, people who are new to the Bible often get understandably overwhelmed. One Bible scholar might read John 10:28-29 and conclude that you can lose your salvation, whereas another one is just as convinced that you can’t lose your salvation. Someone else might read Genesis 1 and conclude that God created the universe in a literal six days whereas someone else might understand Genesis as compatible with the theory of evolution. Does everything, in the end, boil down to personal opinion?

Biblical theology can help lift us out of the confusing mire of competing viewpoints is that it bypasses the flashpoints of denominational conflict by asking a different set of questions. For example, when we look at Genesis 1 through the lens of biblical theology, we are not asking whether God created the earth in 144 hours, but how the creation account relates to the larger themes of the redemptive-historical narrative, such as presence, temple, covenant, and God’s purpose for the earth. Or consider, when we look at Romans 9 through the lens of biblical theology, we are not seeking to understand the order of decrees, or whether it better supports supralapsarianism or infralapsarianism, but the specific Jew-Gentile issues that occupied St. Paul within his specific historical milieu. Or again, when we look at Paul’s letters to Timothy against the backdrop of biblical theology, we are not seeking to know whether the correspondence supports a two-elder view, a one-office view, or a Presbyterian form of government. Rather, we are seeking to discover what 1st and 2nd Timothy show us about God’s unfolding plan as the church straddles the interval between the inauguration and consummation of Christ’s kingdom.

This is not to say that the other questions aren’t important. But sometimes we can get so wrapped up in the questions we want scripture to address that we fail to read scripture on its own terms. Biblical theology, especially when grounded in historical context, is a way to take off our blinders and start viewing the scriptural story on its own terms.

Reason #2: Biblical Theology Offers Context to Theological Doctrines or Concepts

One unique contribution of biblical theology is that it offers context to biblical doctrines upstream of systematic and dogmatic theology. The data that systematic and dogmatic theology work with (e.g. doctrines like the Trinity, the atonement, regeneration, faith, etc.) were originally derived from the redemptive-historical story told across the Old and New Testaments. Yet we often treat these doctrines as intellectual problems to be puzzled over outside the redemptive-historical context in which they were first birthed. This approach can sometimes diminish our understanding of the full richness of a doctrine or, worse, lead us to the type of distortions that arise when we project later theological developments back into the original biblical language while thinking we are being faithful to scripture.

Take an issue like the gospel. Most Christians in the modern world talk about “the gospel” without necessarily understanding where the term came from, and what it meant in its original context. Consequently, when we read about the proclamation of “glad tidings” or “gospel tidings” in Luke 2:10, we are apt to interpret the term in light of what we mean by it. For example, in modern America it has become routine to understand “the gospel” as a procedure for how to get saved, or else a shorthand way of referring to the message that you can go to heaven when you die. Many times we then read back this more modern understanding into the biblical texts. One of the tools of biblical theology, historical context, enables us to peel back the layers to see scriptural texts afresh based on their original context. So we might ask, questions like,

- How would a first century Jew have understood the term “the gospel”?

- How might a Gentile in the Roman empire have understood “the gospel”?

To answer the first question takes us deep into seventh century BC Hebrew history, when men like Isaiah prophesied about gospel tidings against the backdrop of their social-political context. To answer the second question takes us into the world of classical antiquity, a time when Roman emperors frequently proclaimed glad tidings of peace brought by their reign. Understanding all of this offers context, color, and greater depth of meaning to a theological concept like the gospel, including how the “gospel tidings” proclaimed in Luke 2:10 both drew on, and disrupted, previous understandings.

This deeper context to the gospel might be invisible without the specific tools of biblical theology. No matter how much you leverage the tools of exegetical theology (lexicons, word studies, etc.) and no matter how much you leverage the tools of dogmatic theology to see how various catechisms and creeds have understood the gospel, and no matter how much training you receive in pastoral theology on how to spread and apply the gospel, and no matter how educated you are in historical theology to see how different saints and Christian figures understood and interpreted the gospel, there are still some things you might never know about the gospel without the tools of biblical theology.

Even as biblical theology provides valuable context for terms or doctrines that have developed a life of their own in systematic, dogmatic, or historical theology, its tools can sometimes yield surprisingly disruptive readings. For example, it can be unsettling to discover that key theological terms like “justification,” “propitiation,” and others have evolved in ways that are quite disconnected from the narrative in which those concepts were originally understood. Sometimes the decontextualization of doctrines from their original narrative context leads to catastrophic results, as in theories of penal substitutionary atonement which assert that God the father vented His wrath on Jesus instead of us. But when we understand the atonement, not as an isolated bit of spiritual mechanics, but in the context of the symbols and patterns throughout the redemptive-historical narrative, then new avenues open up for understanding Jesus’s life-giving death.

Even as biblical theology offers context to the ideas used in systematic and dogmatic theology, it also offers context to historical theology. We can study what Martin Luther or Louis Berkhof taught about covenant or election, and as useful as that is, it remains true that their understanding is purely derivative, as concepts like covenant and election were originally birthed in the redemptive-historical narrative that is the focus of biblical theology. This realization challenges extreme positions taken by communions that place a high emphasis on the authority of tradition, such as Roman Catholicism or Eastern Orthodoxy. When talking to people in these communions, I have sometimes found leaders downplaying biblical theology in favor of historical theology. At its most crude, those espousing such a framework assert that effective biblical interpretation must simply seek out what the majority of Church Fathers taught about a passage. But where did the church fathers originally get their doctrine from? They were students of the Bible. Consequently, participating in the mind of the Fathers means attending to what they themselves were attending to—the redemptive-historical narrative of Scripture, which lies at the heart of biblical theology.

Reason #3: Biblical Theology Helps Spotlight Key Themes

Biblical theology also helps us spotlight certain key themes that recur throughout biblical history and achieve symbolic resonance as God’s revelation unfolds. Topics like water, clouds, bread, fire, wind, etc. are like recurring motifs in a symphony that gain meaning as the music unfolds. Take bread. While we could zero-in on verses like, “I am the bread of life,” (John 6:35) and look up the original Greek, the exegetical context of John 6, how various people in history have interpreted this verse, etc., you will attain to the richness of this passage without the perspective of biblical theology, and the ways bread recurs throughout the various epochs in God’s unfolding revelation. I have found it particularly beneficial to use a biblical theology framework to understand technology (see my article “Technology and the Story of Redemption: Being the People of God in a Mechanized World“) and same-sex relationships (see my article, “Why the Same-Sex Relationship Debate Needs Metaphysics and Redemptive-Historical Readings.”)

Reason #4: Biblical Theology Gives Context to Our Lives

When St. Paul said that we are Abraham’s offspring (Gal. 3:29), what did he mean? More specifically, how do we living in the twenty-first century, fit with events we read about in the Old Testament that took place thousands of years ago? Biblical theology seeks to provide answers to these questions and thus to provide context to our own salvation journey. You might think of this like marriage. When a man loves his wife, he wants to know as much as possible about her past history: to meet her family, and to immerse himself in her culture, to find out all the details about the background that contributed to the unique person she is today. Ultimately, he must understand her story in order to become part of it himself. So it is with our redemption. A person can certainly be saved without understanding the larger context of the salvation story, just like a man can still be married without understanding his wife’s background, But in order to understand, appreciate and fully enter into our salvation story (even to enjoy it in a rich and meaningful way), we need context; specifically, we need to understanding something of the larger story God has invited us to inhabit.

It is not always easy to connect with that larger story since many of us have come to conceive salvation in individualistic terms. But the tools of biblical theology point to the fact that our redemption is happening in the context of God ransoming the entire cosmos. Understanding this larger—cosmic-–story gives context to our lives, situating our own salvation in a much broader spiritual drama.

Reason #5: Biblical Theology Helps Us Avoid Moralism and Legalism

When we do not understand scripture as a continuous story, then its ability to critique our behavior and thinking becomes limited to mere moralism. This can be seen by taking two quite common examples: drink and sex. Anyone wanting to prove that drunkenness is wrong has a ready supply of verses to clinch the case. Similarly, anyone wondering about sexual ethics can quickly settle the matter with any number of scripture references. This is the moralistic approach, and there is nothing wrong with it. In fact, it would be wrong not to have a strong sense of God’s rules, rooted in divine revelation. But there is a story that is prior to all the commandments. In the case of drunkenness, for example, a person who drinks irresponsibly needs to be confronted with the story of God bringing His people to sound mind, calling them out of the wilderness of the passions into the Edenic new creation of maturity, self-control, sobriety, and wisdom. This is a thousand-year-old story that began in the Garden and continued through God’s call of Israel—a story that will reach culmination when Jesus returns and brings to fruition the new creation project. Similarly, the fornicator needs to understand that the problem with sex outside of marriage is not simply that this behavior happens to violate isolated Biblical commands, but that it runs counter to the whole story of man and woman in Scripture, from the creation of Adam and Eve through to the marriage of the lamb Revelation 19:6-9. The ordering of physical intimacy within the context of marital stability and sexual complementary is part of the larger narrative of becoming fully human so we can realize our primordial telos. Men and women are called do more than simply obey rules; rather, we are called to participate in the story God is writing for the world and humanity—a story which calls us to leave behind our passions of animalistic impulses as we seek to order ourselves according to a horizon that is both soteriological and eschatological.

This storied approach to morality runs like a thread throughout the entire law and prophets. When Moses proclaimed the Ten Commandments to the people of Israel, He put these rules in the context of their own story and history. In Deuteronomy 5:1-5, before recounting the actual commandments, Moses retold the story of the covenant God had made with His people. Similarly, when the laws are recounted throughout the Pentateuch, the Lord often explains their justification with a reminder that He is the one who delivered them out of Egypt. Throughout the checkered history of God’s covenant people, His method of calling his people back to holiness is usually always to review their story, stretching back to Abraham, or even earlier to Adam and Eve.

Through virtues like chastity, temperance, peaceful speech, etc., we become links in a chain stretching back to Adam and Eve, and stretching forward to the final renewal of the world that Orthodox and Catholics in the Byzantine tradition pray for during every Orthros service:

Let us pray to see the true peace of the Age to Come, where there is no more pain, no sorrow, no groaning from the depths, in the wondrous Eden fashioned by Christ, for He is God coeternal with the Father.

Reason #6: Biblical Theology Emphasizes the Unity and Inspiration of Scripture

To even say that the biblical narrative is the story of redemption is to assert that the scriptures do, in fact, tell a single unfolding story. On the face of it, this can seem a preposterous claim. What does a bronze-age text like Job have in common with a letter that a Roman citizen in the 1st century wrote to a slave owner named Philemon? How can wisdom literature like Proverbs be part of the same overarching story as John’s apocalypse? The answer, of course, is that all the scriptural texts are connected through being part of the same story God is telling. Yet the very premise that the disparate books of scripture are part of a story God is telling points to the fact that these texts are from God, which is to say, inspired. Thus, by emphasizing the unity of scripture, biblical theology points to the doctrine of inspiration. This, in turn, helps us avoid reading scripture in fragmented way, as we might be tempted to do if we believed the scriptures had a merely human origin.

We might think of the unity of scripture like a musical symphony. In a symphony each instrument has its unique part to play: there are the violins, the trumpets, the percussion, etc. If you just listen to each part or section separately (e.g. listening when a clarinet player is practicing by herself), you would miss the united experience of the symphony. Similarly, although the books of scripture are very different, they each play a part in the overall song, which is the inspired story of how God is healing the cosmos.

But what do we mean when we say this story is inspired? In reaction to higher criticism and various forms of theological liberalism in the 19th and 20th centuries, some forms of Protestant fundamentalism began emphasizing that all the details of scripture must be factually correct with the same precision we would expect from a police report or an encyclopedia article. Now to be sure, all the latest archeological evidence points to the veracity of scripture in a vast minutia of details, yet that is not what most Christians mean when they speak of scriptural inspiration. To say that scripture is inspired (“God-breathed”) means many things, but in relation to the Bible’s truthfulness, it means that scripture fulfills its claims and that the texts, when understood according to the authors’ intended meaning, are trustworthy. But this requires us to give attention to (1) the types of claims each biblical author is making, and (2) what each biblical author intended to mean. To determine either of these, we must become familiar with the literary genre and historical context of each book.

Because the literary genre and historical context of each book is different, giving attention a book’s context is like listening to different instruments in a symphony. But of course, we will never understand the different parts of a symphony unless we listen to them together in the aggregate. We do this with scripture too. When we talk about the scriptural texts in the aggregate (i.e., when we refer to “the Bible” as if it were a single book) we can say that scripture makes good on its purpose in telling the story of redemption, or what biblical theology calls “the redemptive historical narrative.”

Understanding scripture as a redemptive-historical narrative both expands and limits what we can expect from scripture. On the one hand, viewing scripture in terms of the redemptive-historical narrative opens up a more glorious vista of possibilities in understanding how the disparate minutia form a single thread in telling a story that you and I are invited to play a part. On the other hand, recognizing that the authors of scripture were inspired to give us what we need in understanding and participating in the redemptive-historical narrative frees us from treating the Bible as a cookbook, science manual, or how-to guide on subjects its authors never intended to address. (This is the problem with much Young Earth Creation, particularly the type espoused by Ken Ham and “Answers in Genesis,” which I have interacted with here and here and here.)

Sometimes false understandings of biblical inerrancy can short-circuit the value, or even the legitimacy, of biblical theology. For example, some people have mechanistic ideas of biblical inspiration which deny the Holy Spirit worked through the personality and historical context of the author. On that view, God took over the hand and mind of the author, as a kind of direct download from heaven. Naturally, if this is how you believe inspiration works, then the historical and literary context of biblical books (two key resources in the biblical theology toolbox) will become irrelevant. The fact that Romans is a letter will make no difference to how we read it; the fact that John wrote his apocalypse during or shortly after the reign of Nero is irrelevant in understanding the meaning of Revelation. Questions of authorial intent can then be dismissed with a type of piety that is eager always to remind us that God is the author of scripture.

Reason #7: Biblical Theology Points to Christ

Perhaps the most crucial reason why biblical theology is important is because it is the method the New Testament writers themselves employ when showing how the Old Testament points to Christ. It is, of course, common knowledge that the New Testament writers constantly cite from the Old Testament, but it is easy to miss the significance of their approach. It’s easy, for example, to think of the Old Testament as a grab bag of isolated prophecies about Jesus that the New Testament writers draw on. On this way of thinking, when we read Paul saying that Christ “died for our sins according to the Scriptures,” (1 Cor. 15:3) we may assume he is referencing certain Old Testament predictions that Jesus fulfilled. But what is actually going on in the New Testament is more amazing: the entire story of the Old Testament—including its long checkered history through creation, fall, election, covenant, slavery, exodus, kingdom, and exile—is leading toward its culmination in Jesus the Messiah. So when Paul says that Jesus died for our sins according to the scripture, he is not referencing this or that prediction, but how Jesus is the culmination of Israel’s story. That is something that is largely invisible without an appreciation of the redemptive-historical narrative that is the focus of biblical theology.

The Importance of the Big Picture

Yesterday during work, a colleague told me about a walk around a lake that she does every weekend with her husband. As the walk was not too far from our college, I decided to visit it after I got off work at 6:00 pm.

It was a beautiful lake, and similarly to my experience last Saturday, I had never heard of this walk even though it was only 20 minutes from work. As my colleague told me that she circumnavigates the lake with her husband in an hour, I decided to have a go at it, confident I could finish before dark. Here are some pictures I took.

As sunset approached, the woods around became awash in vivid yellows and oranges, as the glow of the setting sun dance off everything, making all the shades of light more intense.

But then I began to look nervously at the time. At two hours into the hike, I wasn’t even halfway around the lake. As I progressed, the shadows lengthened and dusk descended.

From the woods I began to hear sounds from the forest from animals I didn’t recognize, and my imagination began to play tricks on me. Finally, I was enveloped in complete darkness.

Yet, through all this, I was okay because I had an app on my phone that was tracking my progress. Ever since an eventful hike in 2019 when I got lost, I have been careful to keep an app on my phone that offers GPS coordinates not dependent on a cellular signal. This enabled me to see where I was in relation to the lake I was circling.

This data from my phone helped me to be confident to ignore the tangled thicket of confusing shapes around me because I knew where I was and where I was headed. Though the scenery around me was unfamiliar, I knew the context of my position.

As I thought about it, I realize that that is a bit like biblical theology: when we navigate through scripture, there is much that is confusing, and it would be easy to lose our way if we didn’t have a “map” to offer context.

What is the equivalent to a map, or a GPS system, when we are studying scripture? Well, our map is the sense of the big picture, the knowledge that scripture is a single story about the healing of the earth. But we need additional maps to help us understand how all the sub-stories and rivulets are part of this single stream. How are the prophetic announcements of Isaiah, or the proclamation of the kingdom in the gospels, or Paul’s discussion of justification in Galatians, part of this larger movement toward the healing of the earth? To answer questions like these, we need the guidebooks. Thankfully, biblical theologians have provided these. They have written books that we can turn to when we get lost to regain a sense of our overall direction, even as during my hike I kept looking at my phone to get a sense of my position. There are many books I could recommend, from scholars such as Meredith Kline, Geerhardus Vos, Kevin Vanhoozer, Fr. John Behr, Michael F. Bird, Peter Leithart, Brant Petrie, etc. However, for purposes of this post, I will limit myself to a few recommendations, and save discussion of the aforementioned authors for later.

- Anything by N.T. Wright. I have already mentioned Wright’s recent release on Acts, but all of his works, whether his treatment of the crucifixion, or his discussion of virtue, or his exposition of the resurrection, or his general explanation and defense of the Christian faith, are helpful because of how he situates every issue in the larger redemptive-historical narrative.

- Sandra L. Richter. I picked up her The Epic of Eden: A Christian Entry into the Old Testament at the Antiochian Village bookstore, and it has been so helpful in demystifying the OT by showing how everything fits together as part of God’s plan to heal the earth. For anyone confused about the OT, I recommend this as a good entry-level treatment. Although much of it was review for me, she brought out some aspects of the OT’s ancient near eastern context that I had never heard before and opened up new vistas for understanding what it means to be adopted into God’s family.

- Podcasters. The podcaster and university lecturer, Seraphim Hamilton, while spanning a variety of theological subdisciplines in his work, offers particular insight in understanding the redemptive-historical narrative. Similarly, Alastair Roberts, whose online commentaries on scripture, follows a biblical theology method. Also, in Fr. Mike Schmitz’s Bible in a Year podcast, he introduces each section with a discussion with Jeff Cavins helping us understand how the various sections of scripture relate to the overall story. Here are direct links to each section:

- Intro to the Early World

- Intro to the Patriarch

- Intro to Egypt & the Exodus

- Intro to Desert Wanderings

- Intro to Conquest and Judges

- Intro to the Gospel of John

- Intro to the Royal Kingdom

- Intro to the Gospel of Mark

- Intro to the Divided Kingdom

- Intro to the Exile

- Intro to the Gospel of Matthew

- Intro to the Return

- Intro to the Maccabean Revolt

- Intro to the Gospel of Luke

- Intro to the Church

- For Children. If you are wanting to introduce children to the redemptive-historical narrative, there are a number of super helpful resources. The Great Adventure Kids Catholic Bible by Amy Welborn, tells seventy Bible stories, from Adam to the Apostles. While there are no end of Bible storybooks available for children, this one has the edge because of using a biblical theology lens, laid out in Welborn’s introduction. It’s also beautifully illustrated by Michael LaVoy, with a color-coded system aligning with The Bible Timeline Learning System. (And for those readers who are scared of Catholicism, there is nothing in the Great Adventure Kids Catholic Bible that a Protestant would object to.) N.T. Wright has taken a similar approach in a book he wrote last year for his grandchildren titled, God’s Big Picture Bible Storybook: 140 Connecting Bible Stories of God’s Faithful Promises. Also nicely illustrated, it walks sequentially through salvation history from creation to eschatology. This is a book I wish I had as a child. Finally, Maura Roan McKeegan has written a series for children that tells Bible stories in ways that emphasize typology at a child’s level, helping to connect the various themes of scripture to the bigger narrative. Very beautifully written and illustrated. I have only read the first one so far, but I am eager to order the others in the series as I am confident they will be equally good.

- The End of the Fiery Sword: Adam & Eve and Jesus & Mary

- Building the Way to Heaven: The Tower of Babel and Pentecost

- Into the Sea, Out of the Tomb: Jonah and Jesus

- Saved by the Lamb: Moses and Jesus

Further Reading