This article forms part of an ongoing series aimed to equip students at classical schools with the skills needed to research for their senior thesis. To read the introduction to the series click here. To access all articles in this series, click here.

In the previous post of this series, we learned that there are two parts of the internet: (1) a public internet that features everything from the fake to the bizarre, and (2) a carefully monitored (“peer-reviewed”) part of the internet, known variously as the “deep web” or the “proprietary web.” We saw that serious research involves using the second of these, which is typically only possible when using the computers at university libraries.

But suppose that while you are researching for your senior thesis, that you can’t make it into a university library to access the types of research databases I discussed in the last post? Are you left to simply flounder in the sea of irrelevancy and fake information?

This is the situation that many high school students find themselves in, including those at classical Christian schools. For many students, public databases like Google and Amazon may be the only search systems they have access to. Many students will simply not live near a university library, while others may live near research libraries but lack the time or transportation resources to travel to the library. While high school students will likely have access to community public libraries, these libraries often lack access to the extensive network of proprietary databases available to college students. Yet high school students are frequently required to write research papers, especially in their senior year, and for students at charter schools or private college prep schools, the expectations for these papers may be quite high. This can present particular difficulties for students researching STEM subjects, where the majority of research is advanced in proprietary journals rather than books. While these journals can usually be obtained for free from public libraries through inter-library loans, students who lack access to proprietary search systems may be unable to find the articles they need. Instead, they will be forced to use Google as their default online retrieval system. While students in public schools, including charter academies, will typically have access to stripped-down versions of some of EBSCO’s databases, these will not be acceptable to students at classical schools with their more limited budgetary constraints.

Thankfully, there are some good options for those students who cannot make it into a library. What was not presented in the previous post is that the internet is not quite as neatly divided into two parts as I implied. The reality is that many libraries and universities have been making their content publicly available, and there is also a move within academic publishing to make journal articles available to the public (something known as “open access”). This means that even when you cannot make it into a library to search their databases, you still have a lot of good options for doing research at home. The tricky part is learning to find the needle in the midst of the haystack, to differentiate the needle from the hay, or even to find the right needle in a haystack full of needles. In other words, when faced with the vast sea of information that makes up the public internet, how do find the reliable resources that libraries have made available?

At first sight, the Google search engine seems like it would not be much use here. The algorithm that Google uses to rank websites, and thus to determine which sites appear at the top of search results, is based on many factors that range from the website’s popularity to the amount of inbound links it has to the amount of money the website’s owners are prepared to pay on SEO. But the truth-content of a website is not one of the factors that Google’s algorithm takes into account (how could it, seeing that machines cannot distinguish truth from error?). Because of this, many teachers at classical schools are rightly suspicious of using Google for serious research. In fact, saying, “The reason I know such-and-such is because I spent some time googling it,” is almost equivalent to a confession of ignorance.

Yet this skepticism of Google is misplaced. Google is a powerful tool, but like any tool, its efficacy depends on the skill of the user. With a little training, any student can learn how to leverage the Google search engine to find information that libraries and universities have made public while filtering out everything that is irrelevant. Daniel Russell, who works as a research scientist for Google, made a telling observation in 2019:

“…sometimes I’ll see searchers spending thirty minutes searching for something that should take less than two minutes…. We try to build as much as we can into the search algorithm, but people still need to know a bit about what the web is, and how search engines crawl, index, and respond to their queries.”

A little later, Russell added,

“The online world has an immense set of resources at hand, and yet I see that most people don’t really understand how to use it effectively. It’s as though we’ve all been given a Steinway, but we only know ‘Chopsticks.’ Or you just got a Formula 1 racing car, but nobody ever showed you how to take it out of first gear. We have these amazing tools that we just don’t know how to use well.”

An entire book could be written on best practices for using the Google search engine, and Daniel Russell has actually written an excellent book about this himself, titled The Joy of Search. But the majority of the best practices for searching on Google can be encompassed in a handful of search limiters.

Before explaining about these search limiters, it should be clarified that this article is simply about finding good quality information, not evaluating it. Critical thinking and epistemic virtue are required for successfully evaluating and working with the information you find, which is why the next two articles in this series will be devoted to that.

What are Search Limiters?

One obvious problem with using Google for research is that the search engine is too powerful and too effective. After all, Google offers the researcher tens of thousands of results for any one query. It’s like asking for a drink and being given the entire Atlantic ocean. For example, I just typed into Google the following question: “What is the scientific difference between a fruit and a vegetable?” In less than a second, Google returned sixty-two million, eight hundred thousand results. Many of these results were irrelevant to my actual question, yet were displayed simply because the term “fruit” or “vegetable” appeared somewhere in the content. This illustrates a fact that we have all experienced: Google gives us more than we want. Google is a highly effective search engine, yet its effectiveness sometimes backfires.

Because it is impossible to comb through millions of pages of search results, we typically use various means to limit our results. The most popular search-limiting procedure is to simply to look at the first page of results, or perhaps the first two pages, while ignoring everything else. This is a perfectly acceptable way to limit one’s search. However, from the perspective of a serious researcher, there is no reason to assume that the websites displayed on the first page are the most reliable. For example, in the above query about the difference between fruits and vegetables, none of the results on the first page were from universities, library websites, or academic journals. Many of the results were from businesses who are trying to sell something, and had done a good job optimizing their websites to be Google-friendly. The fact that they made it to the first page may only have meant that they had a good SEO (search engine optimization) officer on their staff. I used to do SEO for a learning company, so I know a little about how the process works, and how content can be manipulated to get on Google’s first page of results.

There are other ways of limiting a Google search besides simply looking at the first page. These search limiting techniques take hardly any extra time in the initial Google Search, but can save the researcher hours of time in the long run. Below we will discuss six different types of search limiters.

Search Limiting by Domain

Every website has an “address” known as an URL (Uniform Resource Locator). For example, the URL for Google is www.google.com. The URL of Wikipedia is www.wikipedia.org. The URL for the White House is www.whitehouse.gov. The URL for the British Library is www.bl.uk.

In these examples, notice that each URL ends differently. These endings (.com, .org, .gov, .uk) are known as top level domains and function like the zip-code of an address. All the material on the internet is organized according to various top level domains, each of which mean something different. For example, .com is a generic domain that was originally used for commercial endeavors but can now be used by anyone. The domain .gov is reserved for government websites, while .uk is for websites in the United Kingdom. There are many other top-level domains, and Wikipedia has a list of them all at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Internet_top-level_domains.

The really cool thing is that these top level domains can be used to limit a Google search to specific types of websites. The way you limit search results to specific types of domain is by simply adding the word “site:” to the beginning or end of a search followed by a colon and name of the top level domain, such as “site:.com” or “site:.org” or “site:.uk”. For example, if a student is writing a senior thesis on the importance of preserving the British monarchy, and the student wants to search for information on the royal family while limiting results to websites in the UK, then the search query would look like this:

British royal family site:.uk

Similarly, if I wanted to search for information on climate change but limit my search to government websites, then my search query would look like this:

climate change site:.gov

In both of these examples, and in the examples to follow, the limiter can also be placed at the beginning of the search with equal effectiveness. For example:

site:.gov climate change

Remember that earlier in this post I said that many libraries and universities have been moving to open access, so that materials that once would have been limited to the proprietary web are now available to the public. Site limiters are a way to access these high quality materials. To see how this works, let’s return to my earlier query on the difference between fruit and vegetables. Suppose I wanted to only receive search results from websites published by educational institutions, and thus to weed out websites selling fruit and vegetables, or advertising weight loss systems, and so forth. Since the top-level domain for educational institutions is edu, my search would look like this:

what is the scientific difference between fruits and vegetables site:.edu

When I do this, instead of retrieving 113,000,000 results, I get 2,520,000. That is still too many results to read, but the real value of this modified search is not that the results are limited by quantity, but that they are limited by quality. In other words, instead of just giving me any website that happens to be optimized for Google-friendliness, these results are from educational institutions. This includes the websites of universities, research institutes, academic publishers, faculty webpages, and so forth—a wealth of helpful information on the difference between fruits and vegetables.

This does not mean that the results of my .edu search are automatically trustworthy, and a good student will still need to exercise critical thinking and epistemic virtue (the topic of the next article in this series). But at least we have moved from random web surfing to actual research. Through the simple addition of “site:.edu” at the end of our search (which can also be used at the beginning), we have transformed the Google search engine from an overwhelming mass of irrelevancy into a highly efficient database for open access educational resources.

Search Limiting by Site

Just as we can limit by domain, so we can also limit by a specific website. That is, you can use the Google search engine to only search within a specific website. The process is much the same as limiting by domain. Many websites have search functions within them, but there may be times when you want to leverage Google’s powerful algorithm to find just what you need within a particular site. For example, if you are looking for geological information, you might want to search within the website U.S. Geological Survey (www.usgs.gov/). If you are searching for a story you remember reading in the Washington Post, then you might want to limit your search to the Washington Post. To perform this website-specific search, simply put “site:” followed by name of the website, followed by the query, or visa versa. For example, if I am looking for information about earthquakes in Idaho and I want to search within the USGS site, then my query could look like this:

earthquakes in Idaho site:USGS.gov

or

site:USGS.gov earthquakes in Idaho

This method can be particularly useful when you are searching for faculty on a university website. Universities always list their faculty somewhere on their website, but it can be a laborious and time-consuming process to find out where. By doing a site-limited search, a process that might take an hour can take less than 10 seconds.

Search Limiting by Time

Specifying top-level domains are not the only way to site-limit when performing a search. It is also possible to limit a search according to a certain time-frame. A very important part of any research paper is the literature review, where you show the reader that you are aware of what work is already being done in your field. A dead give-away that someone is an amateur researcher is if they reference older sources while ignoring recent scholarly discussions. When discussing the literature on a topic, you want to show familiarity with the most up to date publications and discussions.

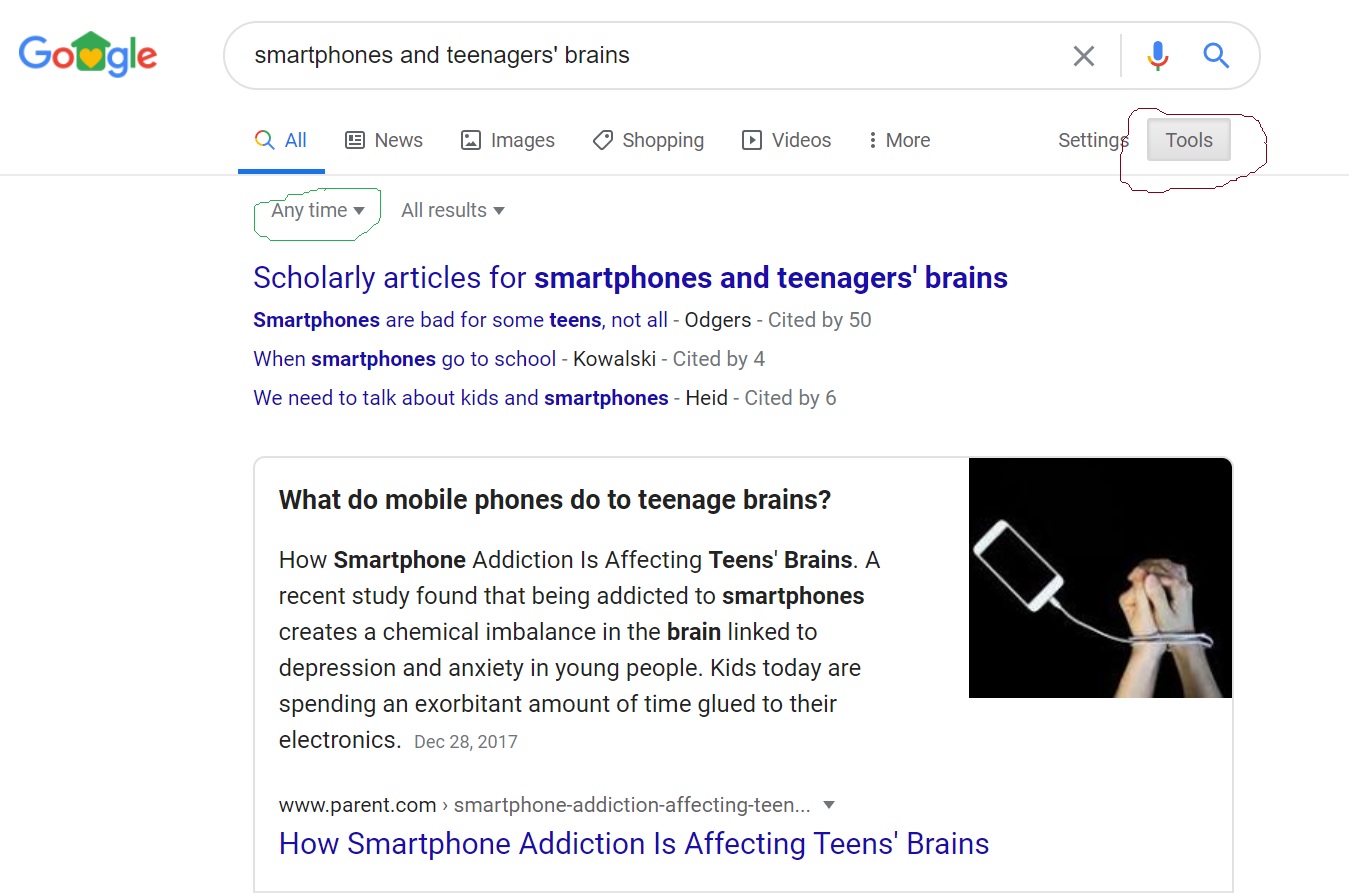

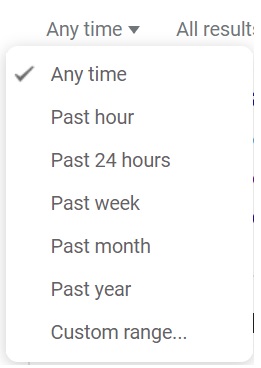

Here again, Google is your friend, since it is possible to limit your Google search to a specific time-frame, say the last five years. For example, suppose you are writing your senior thesis on the impact of smartphones on teenagers’ brains, and your search query is “smartphones and teenagers’ brains.” To limit this search to research published in the last five years, you first click on “tools”, which is circled in red on the Figure below. By clicking tools, the words “Any time” appear on the left, which is circled in green. This is a drop-down menu that allows you to specify the time-frame of the results that will be displayed.

Search Limiting by File Type

Specifying file type is also a highly effective way of search limiting. Conference papers, reports, journal articles and handbooks are often published in pdf format instead of html. Specifying .pdf in your search is a way to access many of these full text documents. The way to execute this type of search is similar to searching for top level domains, but in this case you simply add “filetype:pdf” at the end of your search. When this type of search is executed, only pdf documents display. Clicking on any of the results either downloads the file onto your computer, or displays the document in your browser’s pdf reader. These are often educational materials that have been uploaded by teachers. Let’s suppose that I wanted to research whether exposure to bright light bulbs helps someone to feel happier, and I want to only explore pdf files. In that case, my search query would look like the following:

Do bright bulbs make you feel happier? filetype:pdf

This search yields a number of pdf documents written by educators and therapists about using bright bulbs for therapy. However, when searching for pdf’s it is important to review the host website to see what credentials the publisher or author has. You can do this by copying and pasting the first part of the URL (usually up to the top-level domain) into a new window. For example, in the above query, one of the documents on the first page of results was a pdf with the following link:

www.fammed.wisc.edu/files/webfm-uploads/documents/outreach/im/handout_light_therapy.pdf

This is a leaflet called “Bright Light Therapy: A Non-Drug Way to Treat Depression and Sleep Problems.” The document presents what appears to be an intriguing method for treating mood disorders in the winter months when people living at higher latitudes do not get a lot of sunlight. However, I am unsure if this is genuine science or just pseudo-science from a company trying to sell light fixtures and bulbs. This is where viewing the host website can be useful. Look again at the URL above. To view the host website, you would simply copy and paste the first part of the URL (the part marked in bold) into a new window on your web browser. Alternatively, you can delete everything after the top-level domain (in the above case, everything in blue), and click refresh, but that will make your pdf disappear. In any case, when we arrive at the host website, we see that the paper was published at the University of Wisconsin’s school of medicine and public health. This tells me that the pdf leaflet may be based on genuine research, or at least that it is worth reviewing closer.

Search Limiting by Content

Finally, it is possible to limit a search to types of websites, such as library websites. While the content of most library websites belong to the proprietary part of the internet that is restricted behind a login wall, many also contain materials that are available for free. To access these publicly-available library resources is easy, since all the searcher needs to do is include the term “libguide” as one of the search terms. This is particularly useful if a high school student is seeking to get a quick overview of a topic, but does not need scholarly journal articles. As an example, if a student is researching the War of 1812, he or she could search “libguide War of 1812.” This brings up 42,300 results from libraries all over the English-speaking world. Although many of these libguides link to proprietary resources, the content that is public can be particularly valuable in helping the student become familiar with a subject and to find out about the main source material on that topic.

The process of online information retrieval is only part of the research process, and not even the most important. What is even more important than how to find information, is how to evaluate it, including how to know what information you can trust. That will be the topic of the next article in this series.

Further Reading