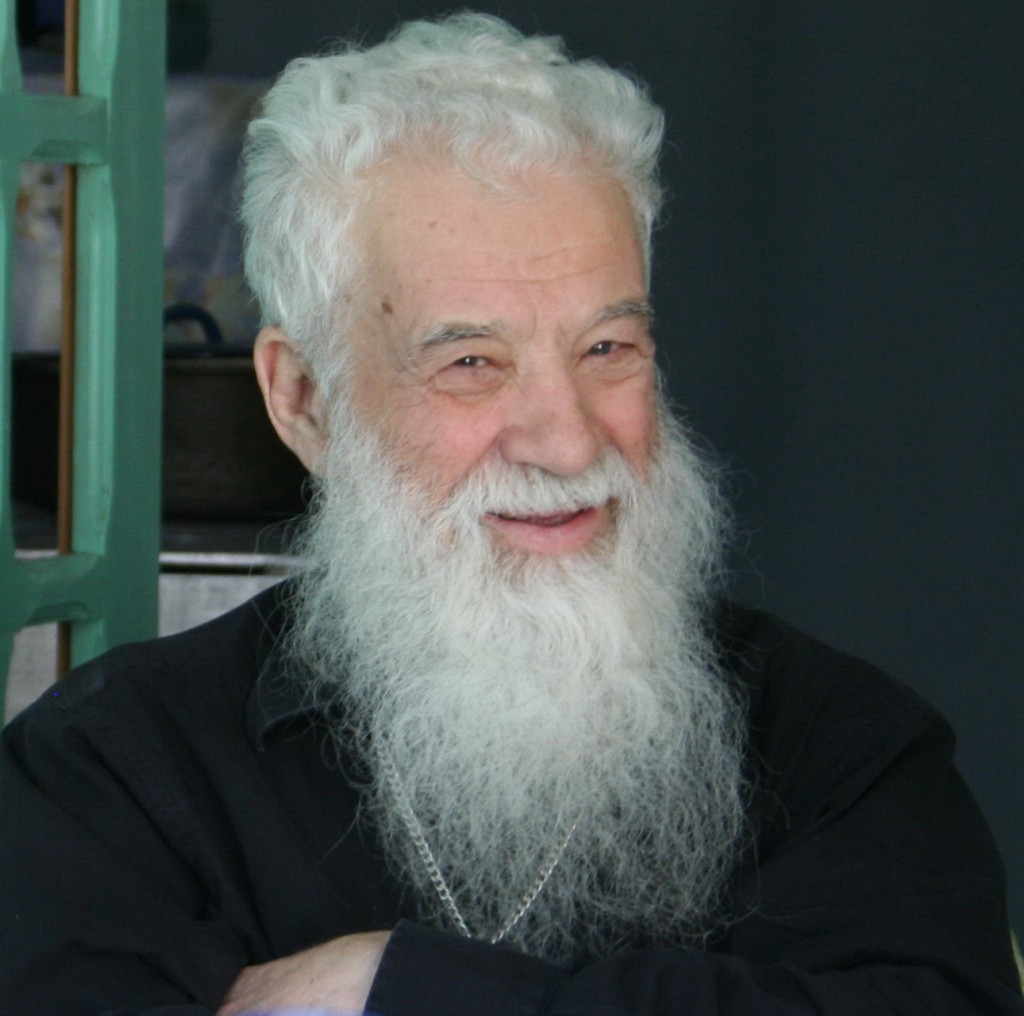

When the Communists took over Romania in 1944, they began rounding up Christians and sending them to prison. George Calciu was one young Christian who found himself caught in the purge.

George was first imprisoned in 1948 and sent to Jilava Prison, and from there to Pitesti Prison. Pitesti was part of an experiment on new torture methods designed to eliminate all vestiges of humanity from the human soul. The goal in these hideous experiments was not simply to pressure the prisoners to renounce their Christian faith; rather, the goal was to break down their entire sense of self, to cause them to forget who they were. The inmates were compelled to deny that they loved God, that they loved their country, that they loved their mother and father—in short, they were made to renounce everything that made them human.

Despite his strong faith, George capitulated and repeatedly denied Christ simply to stop the torture. For him, this was the worst part of his time at Pitesti. While torture damaged his body, denying Christ damaged his soul and left him hopeless.

After three agonizing years, these experiments were stopped because of pressure from the West, and George was moved to a more conventional prison. But the years at Pitesti had left George deeply wounded. Even in the new prison there was little hope of reprieve, because he was expected to spy on the inmates. “There we lost all hope,” he reflected. “There we had no vision. Nothing in front of us. Only darkness and remorse.”[1]

God was with George in the darkness, and gradually he returned to spiritual health by witnessing the faith of priests who had been imprisoned.

But there we met the priests and the monks, and they knew the history of Pitesti. They received us with love and understanding; and they told us about repentance, about the love of God, about the possibility of becoming, again, a Christian.[2]

I changed my attitude—I became more and more mystical. I prayed a lot. I was no longer interested in what happened around me. After my experience [at Pitesti], something had changed in my soul.[3]

After his release in 1964, George married and became a priest in the struggling Romanian Orthodox Church. Father George knew that for preaching against communism he would be imprisoned a second time. Yet he actually welcomed the opportunity to return to prison and not to deny Christ. He was determined to become a martyr rather than capitulate. Thus, in Lent 1979 he began a series of seven homilies aimed at the youth who had never been given a chance to hear about Christianity.

Father George’s homilies attracted much attention, with audiences of up to five hundred people. For many young people who had been brainwashed by communism, this was the first time they were exposed to true Christianity. His sermons integrated Christian theology with analysis of culture, including discussion of the important role of the Church in Romanian society.

Father George knew that his faithfulness would come with a cost. Yet his decision willingly to embrace suffering gave him a courage that was absent when he was simply the victim of forces outside his control. His first imprisonment was imposed upon him, whereas he embraced his second imprisonment as an opportunity to witness for Christ and experience inward growth. There is an important insight here, for the simple act of choosing to embrace our sufferings with courage is a key to spiritual resilience.

Not long after preaching these homilies, Fr. George was arrested on the false charge of being an American agent. In God’s providence, Fr. George survived his second imprisonment, which lasted from 1979 to 1984. By the time he was finally released under pressure from the West, he had spent a total of twenty-one years in prison. Father George eventually settled with his family in Virginia, where he served as priest for a small parish.

When Fr. George gave interviews about his life, he always emphasized the possibility of gratitude, regardless of what is happening around us. He explained that even in the nightmare of communist prisons he could always find reasons to give thanks. He learned to see everything that happened as a manifestation of God’s love for him. For example, he told of being visited by a little cockroach, which eased the pain of his isolation. He commented,

You know, God sent all kinds of beings in order that we would not be alone. I am sure that in every movement, every insect, every conflict with the guards—it was the hand of God that tried to save me, to help me, to make me sure that I was on the right path.[5]

Father George would sometimes talk about his longing for the days of prison when God had touched him in a powerful way. Because his life had been given back to him after he had expected to be martyred, every day became precious. Every day he was alive—even while in prison—was a day to be received with gratitude.

If I came out of prison, I knew that these days, these years of living, after being in prison, were a gift from God. I knew I had to be killed in prison. They had decided that. But God had other ideas. I think that these days, these years, are given to me by God as a gift; and I pay nothing for this gift. I pay no interest on these years of living.[6]

This sense of constant gratitude was contagious. Everyone who had contact with Fr. George remembers him radiating the love and joy of Christ. A 1989 Washington Post article about Fr. George described his gaze as suggesting “the triumph of joy over anguish.”[7] Frederica Mathewes-Green echoed these observations by sharing that “his most distinctive feature was his smile; he had a beaming smile. He was often amused by life, and ready to laugh.”[8]

Being Mindful About Mindset

Father George was able to remain resilient in the face of extreme suffering for a variety of reasons: the Providence of God, his own strong faith, his childlike trust and hope in the Lord, the grace of the Holy Spirit, the prayers of his loved ones, and many other factors. One particular factor I’d like to draw attention to is Fr. George’s practice of reframing.

Cognitive reframing is simply the activity of disrupting negative thoughts with positive thoughts rooted in reality. Just as a frame around a painting lends a perspective, purpose, and context to the work of art, so the mindset by which we frame our experiences determines how those experiences will be perceived and contextualized. Cognitive reframing (sometimes called cognitive restructuring) offers a way to be conscious about our mindset and to look deliberately for positive ways to frame our experiences.

Father George could have framed his life with frustration and discouragement, thinking something like, “I lost over two decades of my life in prison.” But instead, he framed his life positively, based on the reality that every day was a gift that God had given back to him. Father George did not ignore the bad that was happening around him; rather, he chose to focus on the good and to focus on the positive context in which negative circumstances could be situated.

Christ emphasized the importance of reframing in the section of the Sermon on the Mount known as the Beatitudes. Here our Lord takes a number of circumstances that are ostensibly negative (e.g., mourning, poverty of spirit, being persecuted, being reviled, being the victim of evil speech) but then added a spiritually positive twist to each.

Similarly, the Apostle Paul practiced reframing in his own life. In his second letter to the church at Corinth, he shared about the enormous trials he had faced in Asia. Paul’s suffering had been so intense that he and his companions were “burdened beyond measure, above strength, so that we despaired even of life” (2 Cor. 1:8). But then Paul went on to put a positive frame around the suffering, focusing on the way the trials had helped him and his companions learn to depend on God instead of themselves:

Yes, we had the sentence of death in ourselves, that we should not trust in ourselves but in God who raises the dead, who delivered us from so great a death, and does deliver us; in whom we trust that He will still deliver us, you also helping together in prayer for us, that thanks may be given by many persons on our behalf for the gift granted to us through many. (2 Cor. 1:9–11)

Negative Frames Verses Positive Frames

Imagine you know someone whose boyfriend is always tearing her down. He continually tells her that she isn’t pretty enough and that she is stupid, unable to cope, and nobody likes her. What would you say to her? Obviously, you would encourage her to break up with her negative boyfriend or at least stop paying attention to his continual criticisms.

Even though that is the advice all of us would offer a friend, we often fail to follow our own advice, because we pay attention to negative monologues arising within our own brain. Instead of “breaking up” with our negative brain, letting toxic thoughts flow out as quickly as they flow in, we often pay attention to the negativity. To see if this is a problem for you, just ask yourself the following questions:

- Does your brain amplify your negative traits while minimizing the good that God is working in you?

- In your thoughts, do you show yourself the same loving compassion that you would show toward a loved one?

- Do you spend time engaged in morbid introspection, analyzing yourself and your darker feelings?

- Do you spend more time thinking about what is wrong in your life than about what is good?

- Does your mind make hardships worse by dwelling on them?

- Do you suffer unnecessarily from imagining future scenarios that may never transpire?

- When challenges arise in your life, does your mind send you defeatist messages, or do you analyze strategies to help you rise above the situation and work toward solutions?

- Are there certain negative scripts about yourself that your brain keeps returning to over and over again?

Questions like these are important when assessing the mindset we bring to our lives. Our mindset creates a context in which we interpret what we experience, perhaps without even realizing it.

The frames through which we view our experience do not simply influence the way we think about our lives; they also affect our quality of life. The difference between a life of joy and a life of self-pity lies in the power of these frames, as does the difference between a life of gratefulness and a life of grumbling. As Elder Paisios the Hagiorite observed, “Everyone interprets events in a way that is consistent with his own thoughts. Everything can be viewed from its good or bad side.”[9] Determine to view everything that happens to you from its good side.

Research has found that if we are not deliberate about our mindset, then we naturally gravitate toward negative ways of framing our experience (e.g., the glass is half empty rather than half full). An example of gravitating toward the negative is found in Numbers 13—14. After the people of Israel left Egypt, Moses sent out spies to bring back news of the Promised Land. After forty days, the spies returned and reported what they had seen. They explained that although it was a land flowing with milk and honey, it was fortified by strong enemies who would be hard to defeat. Their report struck terror into the people of Israel, who then began murmuring against Moses.

Only two of the spies, Joshua and Caleb, offered a positive report. They said, “If the Lord delights in us, then He will bring us into this land and give it to us. . . . The Lord is with us. Do not fear them” (Num. 14:8–9). This positive report displeased the people so much that we are told “all the congregation said to stone them with stones” (Num. 14:10).

Although Joshua and Caleb had observed the same reality as the other ten spies, and although they did not deny the presence of strong enemies, they reframed these challenges in a way that emphasized God’s power and providence. Not surprisingly, the Lord was pleased with the positive report of Joshua and Caleb but displeased with the negative report of the other ten.

The thing I find so interesting about this story is that both groups of spies observed the same reality. What differed was not the external facts but the interpretation of those facts. One interpretation was rooted in fear, hopelessness, and lack of faith, while the other interpretation was rooted in confidence about God and His promises.

Sometimes cognitive reframing can be as basic as simply reminding ourselves that somehow God is still in control, that somehow He is working everything together into His sovereign plan for us even if we may not understand how.

By being deliberate about our mindset, we can disrupt negative thoughts and find alternative ways of viewing the same experiences. We can learn, as one ancient prayer puts it, to “bury in me the evil devices of the devil with good thoughts.”[10] By practicing this type of reframing over an extended period of time, we actually effect material changes in our brain, causing growth of new synapses between our neurons.

The Russian mystic and spiritual writer, St. Theophan the Recluse (1815–1894), frequently taught about reframing. In his book The Spiritual Life, he devotes an entire chapter to turning the burdens of life to spiritual profit.[11] He referred to the work of a bishop who took 176 situations and reframed them with a spiritual interpretation. The idea is to get so good at this type of reframing that when something annoying happens, you automatically frame it in spiritual terms. It becomes a kind of challenge: How can I find something good in this? What can I find in this situation that can convert my grumbling into gratitude?

Here are some examples of common negative frames juxtaposed with positive ones.

| Negative Frame | Positive Frame |

| “Difficult things are always happening to me!” | “This is definitely a challenging set of circumstances, but God has given me many resources for coping with this (1 Cor. 10:13). Moreover, my heavenly Father may be trying to teach me something here, perhaps so I can grow in the type of lowliness, gentleness, and longsuffering that Paul talked about in Ephesians 4:1–2.” |

| “These trials are ruining my life and making me miserable.” | “James 1:2–4 tells me to count trials as pure joy because they lead to perseverance and maturity. Praise God for another opportunity to grow spiritually!” |

| “My job is so stressful that it makes me miserable.” | “I’m thankful to have a job at all. Things could be a lot worse.” |

| “Having to deal with this is probably going to wear me out, maybe even push me over the edge.” | “Having to confront this challenge could help me become strong in my faith.” (1 Pet. 1:6–7) |

| “This is just one more example of how things are always going wrong in my life!” | “Okay, things are going badly in my life right now, but I still have a lot to be grateful for.” (1 Thess. 5:18; 1 Tim. 6:6–8) |

| “This could turn out really badly.” | “I don’t know how this is going to turn out, but I do know that whatever happens will offer me the chance to be stretched and to grow in perseverance, character, and hope.” (Romans 5:3–5) |

| “I’m such a horrible person.” | “What a blessing it is that I can always repent and receive forgiveness from God. There is no sin too big for Him to forgive.” (Eph. 1:7) |

| “Bad things are always happening to me. If something doesn’t change in my life for the better, I know I’m going to become more and more miserable and perhaps even sick.” | “This is another opportunity to persevere with gratefulness in the face of difficulties. They say that any skill takes ten thousand hours of practice to truly master. If I have thousands of these difficult experiences, then maybe I’ll develop the spiritual capacity to remain grateful in the face of even more severe suffering, such as persecution or martyrdom.” |

| “I’m so angry that this person has been speaking badly of me to others.” | “Jesus said that we are blessed when people speak evil against us falsely (Matt. 5:11–12). Although what is happening may not feel like a blessing, I believe God when He says it is.” |

The difference between a thought-life characterized by the left column rather than the right column is not found in the actual circumstances a person confronts. On the contrary, the perspectives in both columns are different possible reactions to the same events. But whereas the reactions on the left can lead to depression, paranoia, self-pity, and hopelessness, the reactions on the right lead to gratitude, hope, self-compassion, and peace.

Notice that I left the last three sections of the above table blank. These are for you to fill in with challenges from your own life. It’s simple: the next time something difficult happens to you, write down the negative way you could be tempted to view it. But then write down a positive way of framing the same circumstance, preferably one that is rooted in Scripture. The key is to be mindful about your mindset instead of just defaulting to a perspective of negativity.

Also notice that the positive frames on the right are all based on biblical teaching and divine promises. This is important, because positive reframing is not about being unrealistically optimistic, nor is it about tricking your brain to feel good when you are really miserable. You will not grow spiritually by disrupting negative thoughts with happy images of rainbows and bunny rabbits, or by eating chocolate (see the error of sentimentalism). In fact, sometimes the most positive thing a person can do is to acknowledge what is wrong in his or her life.

The key to reframing is to align your thinking with the objective reality of God’s promises, together with the comfort, hope, and confidence those promises bring. Remember, Joshua and Caleb did not deny the presence of strong enemies in the Promised Land, but they viewed these challenges through the lens of what they already knew to be true about God’s providence.

Putting this into practice, the next time something bad happens to you, write down a negative perspective you could adopt and a positive scriptural perspective. Then ask yourself: Which of these competing perspectives is most in line with reality? As you do this, remember that reality is not based on your subjective feelings, but on God’s objective promises. God’s promises are true even if your feelings are telling you something different.

Reframing With Three Simple Promises

Let’s do a little thought experiment. I’d like you to imagine living in a world where every person has his or her consciousness continually focused on loving you. Moreover, imagine living in a world where every single person is continually working to arrange things for your good.

Once that image is fixed in your mind, ask yourself this question: If you lived in such a world, would you ever have cause to worry or experience anxiety? Would you ever have a need to grasp good things for yourself?

Now let’s leave this imaginary world and move to the real one. The glorious reality is that if you are in Christ Jesus, then you are actually in a better position than if every single person in the world were continually arranging things for your benefit. This is because God Himself, the Maker and Sustainer of the entire universe, has His infinite attention continually fixed on arranging every circumstance for your benefit (not what you want, but what will truly benefit you). All the twists and turns of your life, including those that you might not have chosen, have been especially customized by Providence to assist in your spiritual growth and ultimate well-being.

I never appreciated this truth until I discovered the writings of the Desert Father St. Dorotheos of Gaza, also known as St. Dorotheus of Palestine or Egypt. This sixth-century saint wrote these counsels for the benefit of younger monks who had gone into the desert to devote themselves entirely to prayer. He offered instruction on everything from dealing with distracting thoughts to the right attitude to adopt toward those who have wronged us. One of the points St. Dorotheos developed at length is the absolute security Christians can gain from recognizing that God is orchestrating all things for our benefit. The saint seems to have based this teaching on the following three promises given in Scripture:

- The love of God that has been poured out on us is so strong that no conceivable hardship can separate us from that love (Rom. 8:35–39).

- Everything that happens to us is organized by Divine Love for our benefit, even if we can’t understand how (Rom. 8:28; Matt. 10:29–31).

- In response to this love, we are enabled to replace anxious thoughts with a moment-by-moment awareness of all that is lovely, noble, and good (Phil. 4:6–8; 1 Thess. 5:16–18; Luke 12:29).

Reflecting on these and similar scriptural promises, St. Dorotheos explained that the Christian can be completely relaxed in the certain knowledge that everything has been orchestrated by our Divine Lover. His reflections culminated in this marvelous passage:

And he must believe that nothing happens apart from God’s providence. In God’s providence everything is absolutely right and whatever happens is for the assistance of the soul. For whatever God does with us, he does out of his love and consideration for us because it is adapted to our needs. And we ought, as the Apostle says, in all things to give thanks for his goodness to us, and never to get het up [sic] or become weak-willed about what happens to us, but to accept calmly with lowliness of mind and hope in God whatever comes upon us, firmly convinced, as I said, that whatever God does to us, he does always out of goodness because he loves us, and what he does is always right. Nothing else could be right for us but the way in which he mercifully deals with us.[12]

To believe in God’s promises in the way St. Dorotheos describes does not mean you will never feel confused, lonely, vulnerable, anxious, or insecure. Rather, it means that you can turn to God in and through these difficult conditions. The more you turn to God, the more you can begin seeing all that happens to you as organized by Divine Love for your benefit. Consequently, you can believe that there must be a positive purpose to even the most challenging circumstances. You can begin to see all trials as opportunities instead of obstacles (James 1:2–3).

Remembering God in Our Suffering

Even though God arranges all trials for our benefit, we do not always understand how. In most of the trials we face, the ultimate purpose remains hidden from view. That is where it is so stabilizing to place confidence in God’s promises rather than in our own reason. God’s promises assure us that there must be a positive purpose to even the most difficult trials, regardless of whether or not we understand it. When Joseph was sold into slavery by his brothers (Genesis 37) and later thrown into prison (Genesis 39), he had no idea how the Lord was using it for good. It was only much later, after he was in a position to deliver his family from famine, that he was able to reflect back and say, “God meant it for good, in order to bring it about as it is this day, to save many people alive” (Gen. 50:20).

A New Testament example of the same principle occurs in John 11, where we read the story of Lazarus’s sickness and subsequent death. Before his death, his sisters sent for Christ. Given that Jesus particularly loved this family (John 11:5), one might naturally have expected Him immediately to depart for Bethany to heal His friend. But instead, Jesus delayed. When He showed up four days after Lazarus’s death, Martha exclaimed, “Lord, if You had been here, my brother would not have died” (John 11:21). The sisters were suffering, not just because they had lost their brother, but also because they felt let down by Christ. Where was He when they needed Him the most?

Most of us can relate to Martha. Often our sufferings are increased by feeling that God has let us down, that He has forgotten about us and our loved ones. At the time, Martha and Mary could not possibly have imagined the greater glory Jesus had in mind to accomplish through the delay. In hindsight, Christ’s delay in helping the family makes total sense. After all, the miracle of raising Lazarus from the dead became a pivotal turning point in His ministry, leading to the conversion of hundreds.

But usually the reasons for the Lord’s work remain obscure and even confusing. Why didn’t He save Deitrich Bonhoeffer from hanging? Why didn’t He save six million Jews from the gas chambers? Why doesn’t He save us from whatever suffering we are currently experiencing that feels overwhelming and crushing? We don’t have the answers to these questions, and this often compounds our suffering. Like Mary and Martha, we feel that the Lord has let us down or even betrayed us for no apparent reason. In these times of confusion, Jesus’ response to Mary and Martha is comforting. When Martha shared her feelings with Jesus (John 11:21), and later when Mary did the same (11:32), He did not rebuke them for complaining and feeling confused. Instead, He identified with their pain, even weeping with them, while gently directing their attention to God’s presence (John 11:35, 40–41).

Imagine a child who is lost and confused, and then suddenly his father appears on the scene. Even though the child may still be confused about where he is, the presence of his father causes him to be flooded with a sense of incredible peace. That is how the remembrance of God can be for us: when we turn to Him in our difficulties, we can experience a peace that is not dependent on understanding where we are, where we are headed, or how everything will eventually work out. In God’s arms, we can be like a little child whose entire experience is bathed in his parents’ love.

This remembrance of God’s presence, combined with a childlike faith in His promises, sustained Fr. George Calciu through decades of imprisonment. Father George knew that whatever might happen to him, the Lord was there with him. Convinced that everything he experienced was part of God’s perfect plan for his life, Fr. George was able to see obstacles as opportunities for spiritual growth. Even when anticipating his own untimely death, he took courage in God’s promises and His care. This enabled Fr. George to view everything that happened as a manifestation of God’s love. Father George did not understand what was happening, nor was he able to explain why God was allowing so much suffering; yet he knew it was somehow part of God’s perfect plan for his life.

Endnotes

[1] George Calciu, Father George Calciu: Interviews, Homilies, and Talks (Platina, CA: Saint Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2010), 228.

[2] Calciu, 228.

[3] Ibid., 34.

[4] To learn more about responding to stress as a voluntary challenge, see my online article “Positive Self-Talk and Anxiety” at www.robinmarkphillips.com/anxiety/.

[5] Calciu, 84.

[6] Ibid., 91.

[7] Ibid., 44.

[8] Frederica Mathewes-Green, Introduction in Calciu, 11.

[9] Saint Paisios, cited in Trader, Ancient Christian Wisdom and Aaron Beck’s Cognitive Therapy, 52.

[10] Orthodox Eastern Church, A Manual of Eastern Orthodox Prayers (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1945), 67.

[11] St. Theophan the Recluse, The Spiritual Life (Platina, CA: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 1995).

[12] St. Dorotheus of Gaza, Discourses and Sayings (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1977), 192.