I grew up in an environment of books. Not only was my father a writer and editor, but he also owned a publishing house and a bookstore.

Sometimes after school I would walk over to my Dad’s bookstore, four blocks away, where I loved spending time in the children’s section. I remember lying on the couch spending hours reading Anne of Green Gables and other books about interesting quirky people or animals. Sometimes I became so engrossed in the stories that they started to seem more real to me than the outside world. I didn’t have a lot of friends but the characters in books became my friends, and often the imaginary worlds in books started to seem more real to me than the actual world.

My mother also loved books. She homeschooled me and my brothers and was always deliberate about devoting a large part of our school day to reading aloud to us. I never thought of reading as “schoolwork,”– it was just something we did for joy.

At some point, I wanted to be literary, and so I started reading books that I thought an educated person would read. I got fixated with having to finish every book, even if I wasn’t enjoying it, just so I could say I had read that title. Add to this the fact that I wasn’t a fast reader, but slowly subvocalized every line, and the result was frustration. I began beating up on myself that I couldn’t read faster. I felt burdened about how many books there were to read, and how long it would take me to get through them all. Reading turned from a joy into a chore.

Because I always had an interest in the Big Questions, my father recommended I read C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity when I was fifteen. That opened up entire new vista of books for me, many of which were in my father’s bookstore. I began devouring Christian apologetics and philosophy, especially books by Peter Kreeft. But again, my reading was agenda based, as my engagement with books was a way to get my questions answered, to figure out the world, and to try to shore up my security in the Christian faith. In short, I read because books were useful to me.

There is nothing wrong in reading books for their usefulness. I am who I am today because of the books I’ve read. But I lost some of the early joy I had in reading as an end in itself, rather than a means. But then—also in my mid-teens—something happened to rekindle my early joy of reading. I discovered books on tape.

In the 90s there were few audiobooks around, but one day when I was at my father’s bookstore, I saw some tapes of The Living Bible from Tyndale publishers. Being allowed to grab anything off the shelves I wanted, I took the tapes home and devoured them. I decided to find out where I could get more books on tape (or, as they were sometimes called back then, “talking books”). After a little research, I discovered that there was a mail-order library of Christian books on tape for blind people. I wasn’t going to let a little thing like the fact I’m not blind stop me from accessing this treasure trove. I did a little name-dropping and mentioned to the lead librarian that I was the son of the Christian author, Michael Phillips, who was one of the most popular authors in their lending library. “Of course you can borrow some of your dad’s books on tape even though you aren’t blind,” she said. So I began acquiring some of my father’s edited editions of George MacDonald’s novels, and then went on to borrow the tapes of Treasure Island, Wuthering Heights, and others that I can’t now remember.

I don’t know why books on tape bypassed the fixation with utility that had characterized my previous reading. I think part of it may be because the narrative is a fixed speed, and so I didn’t feel the pressure to rush; hearing something read aloud forced my mind to slow down and go with the speed of the narrator. Also, being unable to underline and annotate the audio book liberated me from the feeling of consuming and using the text. Another reason I liked recorded books may have been neurological: I was diagnosed with dyslexia in my visual sequential processing (something that also impacts short-term memory) and was told, following a number of tests, that I am in the lowest 1 percentile of the population. That means that nearly every human being can remember things they see better than I can. So thank God for recorded books!

At some point in my twenties, I reverted back to my old ways and began approaching books for their utility value, now supercharged by an increased desire to be a bigwig intellectual. Gone were the days when I lost myself in a book or was reduced to tears by listening to The Fisherman’s Lady and The Marquis’s Secret (two of my father’s George MacDonald editions that had a profound impact on me). Of all the books I read in my twenties out of duty (because I thought “this is a book that I ought to read”), I cannot recall a single one except for a book on digestion, and the only reason I remember that is because of how boring the book was for me.

I also consumed articles from the internet. I remember struggling to get through a whole stack of Douglas Wilson posts I printed out, because I thought that if I was going to be an intellectual, then I would need to master everything Wilson was talking about. I can’t remember anything from that stack of printouts, only that I felt burdened by all the information I thought I needed to process in order to be “up on everything.”

The only books I remember from that period were ones I read with my children. Children naturally love books for the right reason and never have to be taught that books are to be enjoyed. Often bad teaching destroys this, and we spend the rest of our lives unlearning what we “learned” at school. Part of growing into maturity as an adult reader is to recover the joy books gave us when we were young.

I went through so many good books with my children—some that we read aloud, and some that we listened to on tapes from the library. Some of the favorite books I shared with my children were books by A. A. Milne, G. A. Henty, Tolkien (not only his stories about Middle Earth, but his delightful Letters From Father Christmas), Rosemary Sutcliff (especially her retelling of the Iliad and Odyssey for children, illustrated by Alan Lee), William Nicholson’s The Wind Singer, George MacDonald’s The Princess and the Goblin, Richard Adams’s Watership Down, retellings of great classics by masters of English language Howard Pyle and Roger Lancelyn Green, retellings of fairy tales by Andrew Lang, and on and on. But probably our favorites were C. S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia and Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows. Who could fail to be totally captivated by the unwavering loyalty of the four friends: the infuriating toad, the no-nonsense badger, the unassuming mole, and the amiable rat?

In 2014 when I was 38, I decided to use money from a tax refund to buy a tablet, having been a holdout against hand-held devices until then. For me, the really attractive feature of tablets, and later smartphones, was that they could play audiobooks. Probably more than anything else, that helped in my rediscovery of reading as an end rather than a means, a joyful activity and not a merely dutiful one. I began devouring novels and have never stopped, often combining listening to books with my love for the outdoors and hiking.

In addition to revisiting some of the books I enjoyed with my children, I discovered new writers and genres, including new children’s authors (Jill Paton Walsh, Josephine Tey, Susan Cooper, Katherine Paterson, Cynthia Voigt), delightful Greek playwrights (Aristophanes, Sophocles, Euripides), 18th and 19th century novelists (Jane Austen, Herman Melville, Charles Dickens, Charlotte Bronte, Alexandre Dumas, Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Elizabeth Gaskell, Leo Tolstoy, Bram Stoker, H. Rider Haggard), historical fiction writers (Sigrid Undset, Pearl Buck, Eugene Vodolazkin), journalistic storytellers (Sebastian Junger, Malcolm Gladwell), writers of comedy (P. G. Wodehouse), writers of memoirs (James Harriot, Oliver Sacks, Bill Bryson), writers of science fiction with a spiritual twist (C. S. Lewis, Charles Williams, Stephen Lawhead, Tim Powers, Walter M. Miller, Jr.), 20th century novelists (G. K. Chesterton, John Buchan, George Orwell, Jack London, Dorothy Sayers, Thornton Wilder, Graham Greene, Evelyn Waugh, Umberto Eco) and living authors (P. D. James, Muriel Barbery, Shūsaku Endō, Kazuo Ishiguro, Wendell Berry).

The books that have stuck with me the most are those with characters who defy neat and tidy categories and moralism because they reflect the same complexity and ambiguity as people in the real world—characters who often have to work through pain without any clear resolution yet whose lives nevertheless reflect God’s grace in out-of-the-box ways. I think here of Maurice in Greene’s, The End of the Affair, or Kristin and Erlend in Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter, or Charles in Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, or Sebastiao in Endō’s Silence. Through these and other books I have experienced what C. S. Lewis described in the Epilogue of An Experiment in Criticism: “We want to see with other eyes, to imagine with other imaginations, to feel with other hearts, as well as with our own.”

I have also derived almost indescribable joy from memorizing poetry, something I also like to combine with walks. If the advantage of audiobooks is that they slow you down to the speed of the narrator, memorizing a poem slows one down even more, because you have to spend hours, sometimes even days, on just one stanza. For me, this is a joy because it gives me an opportunity to really soak in the language, and I feel like the poem becomes part of who I am.

As I think back over my life as a reader, I’m reminded of Dr. Johnson’s remark that “A man ought to read just as inclination leads him; for what he reads as a task will do him little good.”

Of course, children must have their inclinations trained so they come to enjoy good quality literature. As I have pointed out on this website before (see here and here), learning to enjoy goodness and beauty can be hard work. But that’s precisely the point: we want our children to learn to enjoy beautiful literature for its own sake, and not simply what it can do for them. Reading is a means for becoming a well-rounded person, yet ironically, in order to leverage reading as a means, we often have to first approach it as an end. As Gracy Olmstead has observed,

“The goods that result from reading—such as deeper understanding of greater cognitive focus, for instance—only come when we fully commit ourselves to the text for its own sake, and not for its side effects.”

The same principle applies to many other areas. Affection within marriage is good for the brain, but if a man holds his wife’s hand merely to leverage neurological benefits, we would be correct in calling this perverse. Saying your prayers before going to bed helps you have a better sleep, but if you say your prayers merely to sleep better, that is a wrong use of prayer.

Paradoxically, in order to reap the benefits of reading, one must approach reading as a joy and not merely as a beneficial activity. As I will be explaining in an upcoming article about reading that will be at my Salvo column next week,

In the contemporary world, we like things that work, and we have never recovered from the fixation with utility wrought in the cultural disruption of the industrial revolution. Consider that even when we revive antient practices that might offer a corrective to the fixation with utility, we often merely leverage these practices for their instrumental value. For example, it is common to practice mindfulness for its health benefits, to listen to Mozart because it’s good for the brain, to hike in order to lose weight, etc. Even beautiful literature and art falls into the orbit of the utilitarian mindset. As C.S. Lewis reflected in An Experiment in Criticism, “The many use art and the few receive it.”

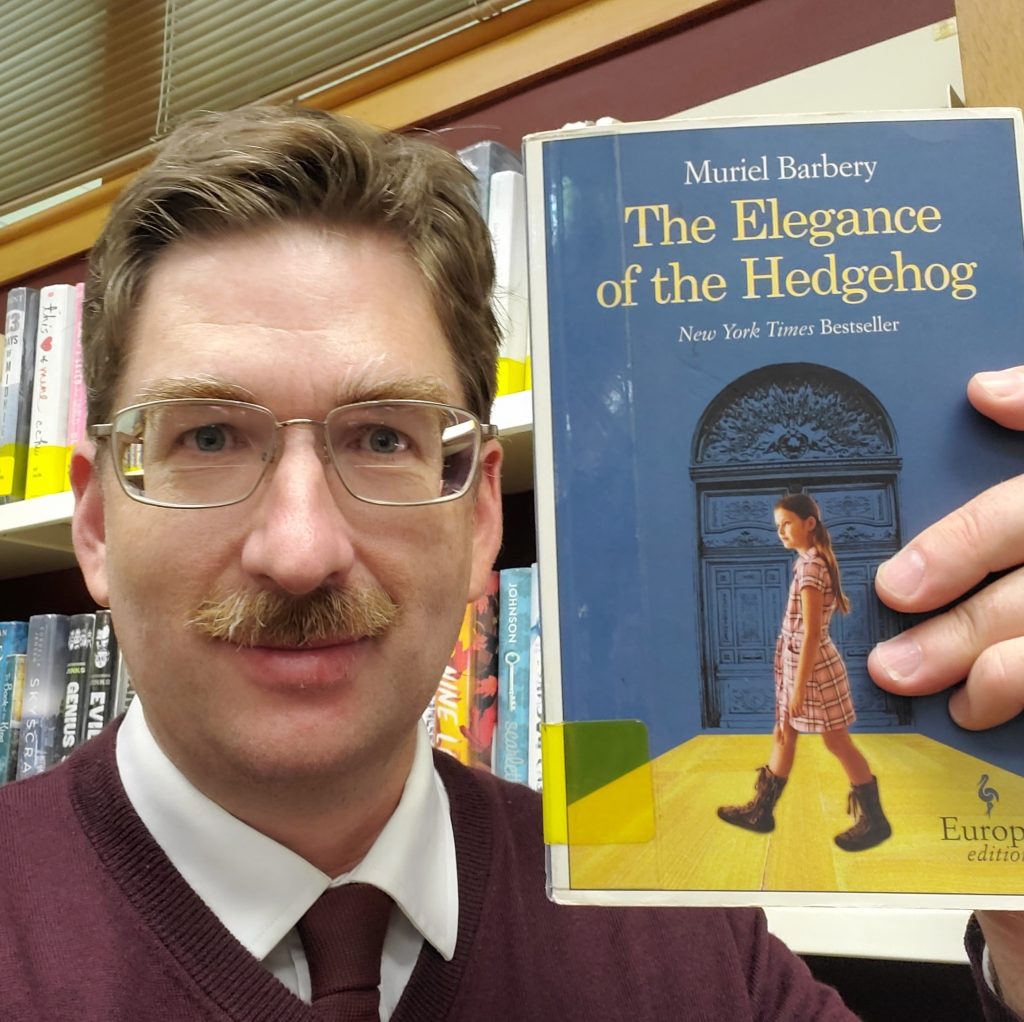

Before ending this post, I want to share about one book that has meant a lot to me and was part of my rediscovery of leisure reading: The Elegance of the Hedgehog, by Muriel Barbery.

Barbery’s French-language novel centers on the parallel stories of two individuals living in the same block of luxury apartments in Paris. One character is a cynical, overweight widow named Renée Michel, who works as a concierge for the rich families in the block. To the outside world, Renée is a typical working-class woman, yet she harbors a well-kept secret. She spends every minute of her spare time indulging her secret passion for the liberal arts, especially literature, philosophy, art, film, and history. Renée goes to elaborate lengths to disguise her passion from the building’s rich inhabitants, for whom learning and the arts are merely tools for advancement and

ostentation.

Renée’s story develops simultaneously with that of Paloma Josse, a twelve-year-old girl whose family lives in one of the luxury apartments where Renée works. The various members of the Josse family are intellectuals, yet for them the liberal arts are a means to pretension, snobbery, and political gain. Overwhelmed by the emptiness and artificiality of her family’s life, as well as her own sense of life’s meaninglessness, Paloma plans to commit suicide on her 13th birthday.

The turning point occurs when a Japanese businessman named Kakuro Ozu moves into one of the apartments and asks Renée about the Josse family. Renée replies briskly, “Every happy family is alike.” Kakuro immediately finishes the quotation from the opening of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina by adding, “But every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” In this sudden moment of recognition, Renée’s secret is out, leading to a series of events in which the lives of Renée, Paloma, and Kakuro become intertwined and transformed.

The Elegance of the Hedgehog is a novel about love, curiosity, sadness, transformation, vulnerability, and the ultimate questions of life. Through the lives of Renée, Paloma, and Kakuro, the reader is invited to celebrate the role that art, literature, history, and philosophy play in human flourishing. These characters see the liberal arts as intrinsically valuable, rather than possessing a merely instrumental value to serve personal agendas. Through the various other characters in the luxury apartments, who serve as foils, we also see how the liberal arts can be subverted when instrumentalized to purely pragmatic ends.