“You Work For Me Now”

Amber grew up in foster care, spending time with various families in Eastern Washington. Although Amber was popular at school and appeared well-adjusted to the outside world, she struggled to believe in her own self-worth. She spent time with some loving families, yet she always knew that people were taking care of her only because they were paid to.

While Amber’s school friends looked forward to growing up and going to college, Amber knew that once she reached seventeen, she would be on the street. Six months before aging out of foster care, at the bus station Amber met a man named Randy.

Randy showed a real interest in Amber and bought her some drinks at Starbucks. It felt special to have someone showing her attention, especially since she had always struggled to feel accepted. Over the next couple of months, Amber met Randy regularly. It was all innocent, and nothing in their interactions would have signaled alarm.

When Randy learned that Amber was about to age out of foster care and had nowhere to go, he mentioned that his friend Craig had a spare room where she could stay for free.

So Amber moved into Craig’s apartment. At first, everything seemed to go alright. She saw a lot of Randy, who would often come over to Craig’s apartment, and who continued to treat her as if she were special.

After a few weeks, Craig asked Amber to deliver a bag to a friend a few blocks away. Amber thought nothing of it and made the delivery. Over the next couple weeks Amber was asked to do more deliveries.

After making about half a dozen deliveries, it began to dawn on Amber that she was delivering drugs. Amber felt she couldn’t say no to Craig since he was giving her a place to stay.

Eventually, Craig and Randy introduced Amber to four other girls who “worked” for them. Everything was clear now: Randy and Craig were pimps, running a highly lucrative prostitution business.

Amber felt betrayed. She has always thought Randy loved her. The sense of being let down simply added to the feeling that she wasn’t worth anything.

Her first instinct was to leave, even though she had nowhere to go. Yet Randy threatened to tell the police that she had been delivering drugs.

“They’ll put you in prison, and the rest of your life you’ll be known as a drug dealer,” he exclaimed. “I’m the only one who can protect you from the police, so get that into your mind. You work for me now!”

The illusion that Randy cared for her was now thoroughly shattered yet Amber felt she had no option but to go along with Randy’s demands. The next thing she knew, Randy made Amber have sex with men she had never seen before. The men paid her, and she was forced to give the money to Randy. This happened about once a week.

Just when Amber thought things couldn’t get any worse, Randy took her on the road with several other girls. A typical week involved being driven along a circuit that stretched from North Dakota, to the mountains outside Coeur d’Alene, to Spokane, to the Tri-Cities, to Seattle, and then back. The women were crammed together in the back of a smelly van, without access to basic sanitation and hygiene (they didn’t stop at rest areas for fear of the girls being spotted).

“I’m Your Only Protection Now”

During Amber’s nightmare on the trafficking circuit, she met Sara. Throughout the long journeys in the back of the van, Amber gradually learned Sara’s story.

Sara’s background had been very different than Amber’s. She had come from a stable Christian family in the Idaho panhandle. When she was fifteen, Sara was invited to a friend’s house and got drunk. Sara never remembered what happened, but a week later she was approached by a stranger. He claimed to have a video of Sara taking off her clothes and asking men to touch her. Sara didn’t believe it until he showed her the video.

“We know everything about you,” the man explained, “and we have the phone numbers of your parents, and all the friends in your youth group.”

The man was Randy, the same pimp who had seduced Amber. Randy explained to Sara that he would destroy the video if Sara did some “work” for him. If she refused, he would send the video to all of her friends. The work would take only a few hours. Reluctantly Sara agreed.

In the weeks ahead, Randy continued to make demands of Sara. The deeper Sara got into Randy’s net, the stronger became the threats against her. The “work” she was asked to do gradually lowered her barriers. Her first job was being photographed topless. Once she got used to this, she was asked to take off all her clothes. Eventually, she was made to have intercourse with men as a matter of routine.

Overwhelmed with shame, Sara began taking the drugs Randy offered her as a way to cope. Eventually she did everything Randy asked her to do, just to get the drugs her system craved.

Even though Sara was living at home, her parents knew nothing of what was happening. When she went to “work” for Randy, her parents thought she was at a friend’s house doing homework. Too ashamed to tell her parents what was really going on, Sara ran away from home a month before her sixteenth birthday. Not long after that, she was put in the van and taken on the road.

A few months later, while being victimized in a rural cabin in the mountains outside Coeur d’Alene Idaho, Sara decided she wouldn’t endure it anymore. This was near enough to where she grew up that she knew she could find her way around. She would walk into town and get help. She didn’t know how she could survive without heroin, but even that didn’t matter anymore. All she wanted to do was to run to her parents and her pastor, explain everything, and ask for help.

Randy had an uncanny ability to sense what his girls were feeling. “You don’t want to run away,” he said to Sara the evening before her planned escape. “Idaho doesn’t have an anti-trafficking law. You know what that means, don’t you?”

“No,” Sara replied.

“It means you will be prosecuted as a prostitute.”

“But you forced me to do all of this!” Sara exclaimed angrily.

“I’m not forcing you to do anything,” Randy replied. “You’re free to walk into town if you want. But just remember, you’re sixteen, which is over the age of consent in Idaho. That means that the police will look upon you as a prostitute and a drug addict. I’m your only protection now.”

Sara relented, convinced that she would never know freedom again.

Thankfully, Sara and Amber were rescued the next day when a traffic cop spotted the suspicious-looking van on a highway in Montana. All the girls were offered care and rehabilitation while Sara was returned to her family. None of them were prosecuted.

Trafficking is Not “Prostitution”

The above accounts are a composite from the stories of real trafficking victims in America’s Pacific Northwest. They illustrate an important point about the difference between “prostitution” and trafficking. One of the common misconceptions about trafficking is that it involves kidnapping. But as the above accounts illustrate, traffickers can use a variety of coercive methods (ranging from violence to sophisticated manipulation techniques) to bring victims into their net.

In the above cases, Randy and Craig had secretly watched Amber and Sara for half a year before making their move. Both men have developed a highly sophisticated sixth-sense that enabled them to identify likely targets and know how best to manipulate them. Randy and Craig were not kidnappers in the technical sense, but they were traffickers, using a variety of means to take away the freedom of their victims.

Sadly, in some states Amber and Sara would have been stigmatized as “prostitutes,” even though they were acting under various levels of fraud, coercion, and manipulation. Pimps will often use quirks in our legal system to leverage their control over victims, convincing children that freedom is not an option.

Pornography and Human Trafficking

I became interested in human trafficking earlier this month when Salvo Magazine sent me to report on a conference at Gonzaga University on how pornography is the new drug. One of the recurring themes at the conference was the connection between porn and human trafficking. Numerous experts, including those with law enforcement backgrounds, shared evidence that pornography is the fuel that drives human trafficking. I will be sharing some of this evidence in my forthcoming Salvo article.

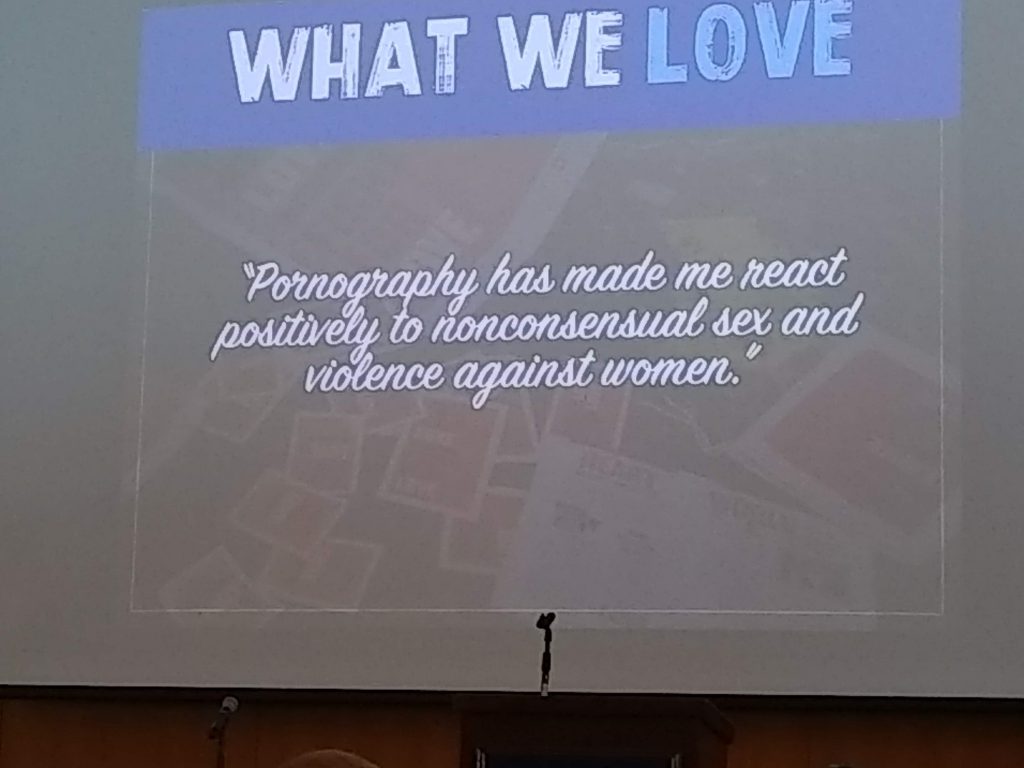

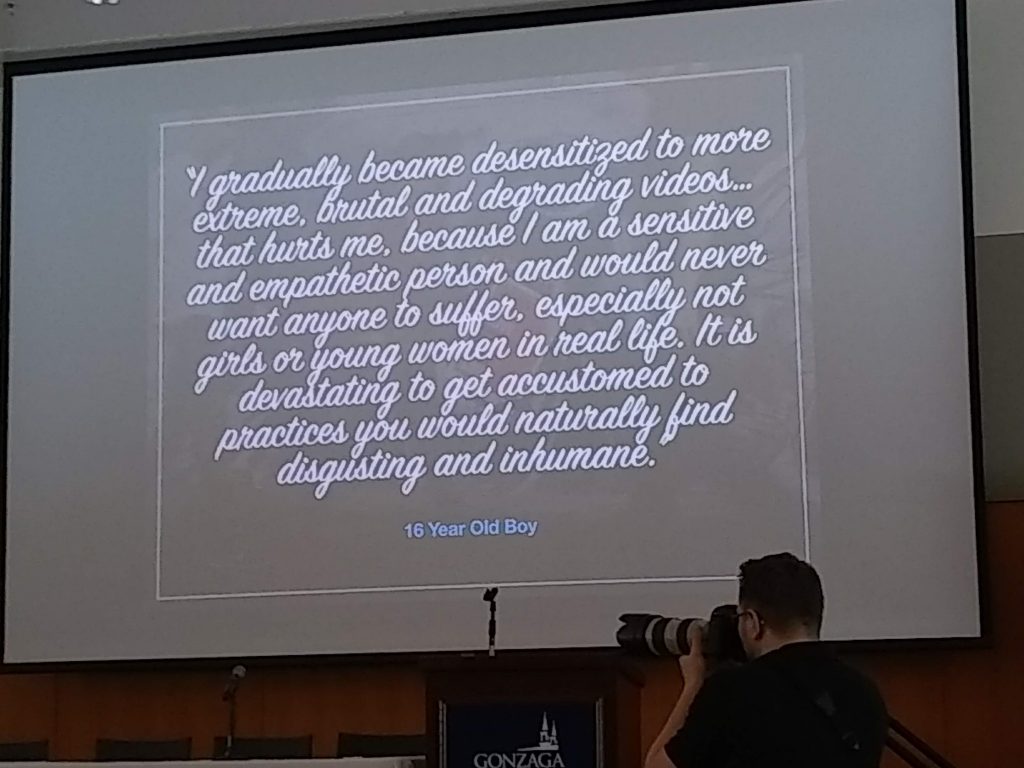

Below are pictures I took from slides at the conference, quoting some of the typical statements that pornography addicts make on the connection between porn and violence.

It is this appetite for violence–and particular the fusion of violence with sexual pleasure–that is sustaining the market for human trafficking in the Spokane area, and throughout all of the United States.

It can hardly be emphasized enough that violence against women has become a systemic part of the pornography industry. 84% of porn sites that have been reviewed show some form of physical violence or verbal abuse against women. If we add global abuse then this figure becomes 90%. According to some FBI estimates, some 25% of actors in porn videos are under coercion in some way. But even when porn does not involve explicit violence, the very essence of pornography is inseparable from treating women as mere commodities–objects to be used rather than persons to be respected, honored and loved. Accordingly, the commodification of women via porn is creating the psychological, neurological and sociological pathways for violence towards women in a range of activities, including trafficking activities.

One of the ways that girls have their barriers lowered is by watching movies that romanticize prostitution and sexual abuse. In her presentation at the Gonzaga conference, Gail Dines drew attention to the way Hollywood films have helped to normalize misconceptions about what it means to be a true man or woman. During her presentation at Gonzaga, Dines pointed out that of the twenty-six Oscar nominations for women who played prostitutes, fifteen won. Of these fifteen, all but one of them portrayed the “happy hooker” image, which offers a romanticized view of prostitution. Through these types of Oscar-winning films, our culture is grooming girls to participate in degrading activities, to become the playthings of unscrupulous men.

The Fight For Freedom

As part of the follow-up research for my upcoming Salvo report, I spent some time doing fieldwork in Spokane. I wanted to learn more about human trafficking and its shadowy links with the pornography industry.

During my research I also learned that traffickers have been preying on the 4,000 plus population of homeless kids in Spokane County. They use these children in a trafficking belt that runs from Seattle to the Tri-Cities to Spokane, along I-90 into Idaho and on to the Dakotas. Many children are removed far from the area, where there is greater risk of them being spotted, and taken to San Francisco, Los Angeles, or San Diego.

One afternoon while I was in Spokane doing fieldwork, I spoke to school children about the issue of trafficking. One person I spoke with was a high school senior name Mirielle Milne. For the last three and a half years, Mirielle has been a Jonah Project advocate, working to raise awareness of trafficking in the city. On March 9th I attended a student-led rally where Mirielle was one of the speakers.

Mirielle gave me permission to publish part of what she shared at the rally.

“One weekend, almost three years ago, I was living at the first safe house the Jonah Project had. A new resident had just come to stay with us. For the most part she was quiet that day. We ate dinner together at the table, we sat in the living room together and colored, and we watched some shows on Netflix. Then I found myself sitting across from this girl listening to her story.

This young lady had been trafficked, as well as abused physically, sexually and emotionally since her childhood. But she didn’t consider that the saddest part of her story. The saddest part was not when she was at the point of going back to her abusers because of being homeless and starving. Nor was the saddest part of her story that she had only been found and come to the safe-house because of being arrested for having drugs in her system—drugs that someone had forced her to take.

That night, she told me with tears in her eyes, that the saddest part of her story was having to watch the evil men in her life abuse her little sister. She was physically and emotionally denied the comfort and peace of mind to protect her little sister from this abuse. That was her deepest heartbreak.”

Mirielle and other students like her are urging the city and state to devote more resources to the fight for freedom. Mirielle is also helping to raise money for The Freedom Railroad, which is a ministry of The Jonah Project to build a series of safe houses that will offer support and protection to trafficking victims. I encourage all of my readers to donate at least $5.00 a month to this worthy cause.

Here is a video I took at the student rally, where students and parents join in a “freedom cry.”

One of the issues that these students are championing is the importance of avoiding the language of “prostitution,” which implies that the victims have a choice. But as I observed above, even when pimps have not technically kidnapped a victim, they use various levels of force, fraud and coercion (including forced drug addiction and threats of violence) to persuade women to “work” for them. Labeling these victims as “prostitutes” shifts the blame away from the criminals who have coerced them.

A Ready Supply of Girls

As part of my fieldwork, I spoke with Scott Jones, former prosecutor in child sex cases, who is now running for the office of Kootenai County Sheriff.

“People have idea this idea,” Jones explained, “that child sex trafficking is about containers of young girls being brought in from Thailand. But that’s not what’s going on, because the traffickers don’t need to do that. Everywhere in America there is a supply of 14-year old girls with home issues and substance issues. Every teenage runaway girl is a potential victim.”

“Fundamentally,” he continued, “what all the trafficking approaches have in common is they find a kid who lacks something—someone who is socially isolated, who doesn’t have friends at school, who doesn’t feel like they’re attractive—and then the pimps offer to fill that void. They’re pretty good at figuring out a girl’s needs and then meeting them. Then at some point in time they tell the girl she has to go to work for them.”

“Typically the longer the relationship goes on the higher the demands become, and the more fear there is of what will happen if she doesn’t meet the demands. There aren’t a whole lot of beatings on the first day, but that starts a few months into it.”

As I spoke with Scott Jones, I asked him why the trafficking victims don’t just run away.

“Imagine you’re a 15 or 16 year-old girl,” he answered. “You’ve met a guy in Spokane, and he takes you to Portland and San Francisco. You make money for him as he sells your services, but he pays for everything and takes care of you. The logistics of running away are difficult for a 15-year old, especially when you add in the psychological connection the traffickers create with their victims.”

I asked Jones about the role of porn in the trafficking culture. “In my work as a prosecutor,” he said, “I review the correspondence between the victims and the traffickers. When looking at the text messages and Facebook messages they exchange, I’m often shocked at how sexualized these victims were at an incredibly early age. That may be because the universe of porn is available to any 11 or 12-year-old with a laptop. So kids are being sexualized far earlier than they would naturally, despite their parents’ best efforts.”

More to Come

For more about human trafficking in the Pacific Northwest, watch for my upcoming article in Salvo Magazine. This article will report on the recent Gonzaga conference on pornography. It will also share more of what I learned from my fieldwork concerning the connection between porn and trafficking in the Pacific Northwest. Also, feel free to browse my archives on porn and immodesty.

Update: the aforementioned article for Salvo Magazine has now been published and is available online.