To read earlier posts in this series, click here.

One morning, on a brisk autumnal day in 2015, I drove myself to the hospital in Spokane Washington. My destination was the office of an expert psychiatrist, Dr. Zimmermann.

After parking my car and finding the appropriate building, I took a long elevator ride to the top of the hospital building where my psychiatrist evaluation would commence.

I had been told that Dr. Zimmermann might be able to help with some mental, emotional and physical problems I had developed earlier in the year. Still, I was a little nervous. I liked psychologists and professional counselors—warm-hearted people who listened to your problems with infinite patience. But I was nervous about psychiatrists, who I envisioned walking around in white coats dispensing prescription drugs that merely masked over people’s real problems. Did Dr. Zimmermann fit the stereotype? I would find out in a few minutes.

As I took the elevator ride, I reflected on the events in my life that had brought me here. In the Spring of that year, I had high hopes for the second half of my life. At the age of thirty-nine, I was completing a PhD in historical theology through one of the UK’s most prestigious institutions. I was also enjoying a growing income from one of my businesses, with dozens of sales reps under me. I planned that after being awarded my doctorate later that summer, I would do postgraduate research at two different universities, one in New York and one in Cambridge, both of which had invited me to investigate how modern technology is gradually changing the way we think about the physical body.

Then everything began falling apart. It started in the summer when I learned that the two men my university had hired to review my doctoral thesis had concluded that my topic was “not an appropriate approach for a doctoral study.” The result, they announced, was that I wouldn’t be eligible for the PhD I had spent the last six years working towards. There followed an exhausting—though ultimately futile—political battle in try to force my university to get another opinion on the thesis. Then the two universities that had offered me research fellowships withdraw their offers. Shortly afterwards, my business started to become less profitable, and I watched my income steadily shrink to a fraction of what I had previously enjoyed. Not long after this, I learned that gossip was being spread about me, damaging some of my closest relationships. Some friends told me what they had been hearing about me, while others simply treated the gossip as fact. I knew something was wrong when one of my closest friends approached me and randomly announced, “You’re evil! And no, I don’t want to talk about it.”

I had always taken pride in my ability to earn money as a freelance writer, but after these struggles, I found myself unable to write. I had various publications willing to pay me for articles, but the burnout and mental exhaustion I was experiencing meant that I could barely string two sentences together. With a wife and three children to support, I couldn’t afford to take time off work, but that is exactly what I ended up doing.

In order not to be a burden to my family, I spent some time with my friends Brad and Sarah Belschner in Moscow Idaho. Every morning when I woke up, I thought, “Maybe this will be the day I’m able to work again.” Invariably, however, I ended up simply wandering around town, battling depressing thoughts and mental exhaustion.

One afternoon, while I was waiting for my friend Brad to return from work, I asked Sarah about some beads she wore around her wrist. “It’s to remind me of a prayer I do, called a breath prayer”, she explained.

“A breath prayer?” I replied. “What’s that?”

“It’s simple,” Sarah said. “You find a short prayer, or perhaps a Scripture verse, and you pray it quietly in sync to the rhythm of your breathing.”

As Sarah was explaining this to me, I remembered something my pastor, Fr. Basil, had shared during a sermon. He had been talking about an ancient Christian prayer called “The Jesus Prayer” which goes like this, “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me.” During his sermon that Sunday morning, Fr. Basil had urged members of his congregation to pray this prayer silently while inhaling on the “Lord Jesus Christ” and exhaling on the “have mercy on me.” I shared with Sarah what Fr. Basil had said.

“That’s exactly the sort of thing I’m talking about,” Sarah replied. “The key is to use the prayer to come to a place of stillness in your own heart, to quiet your busy mind so you can be receptive to the Spirit of God. Sometimes I let the prayer trail out into silence. I just take deep breaths while being in a place of mental stillness alone with God.

Sarah lost me as soon as she started talking about being still with God. I could understand about praying, because it involved words. I have always been a man of many words. But I had no point of contact with what Sarah was saying about mental stillness. You see, from as early as I can remember, my mind had always been busy. This served me well in my professional life, as clients paid me to analyze, research, debate and make new connections. Even when I was not working, my brain was a hive of activity, with thousands of thoughts every minute. When I tried to attend to one thing, I was distracted by thoughts of something else. Even if I had wanted sometimes to be still, I had no idea how.

This mental hyperactivity was playing a large part in my sickness at the time. After the troubles in my life, my energetic brain had turned to rumination, as I suffered from an incessant influx of anxious and stressful thoughts. My brain was like a non-stop radio that I could never turn off.

I used electronic devices as a way to distract me from the inner turmoil I was feeling. I kept a tablet at my side at all times, making it possible for me to constantly check for new messages or status updates, keeping my brain a buzz of movement. When I wasn’t checking my messages I would use my tablet to listen to audiobooks and podcasts, saturating myself in a constant stream of information. But this coping strategy merely masked over the pain I was feeling and exacerbated my mental exhaustion. What I had trouble doing was connecting to the present moment.

Realizing my problem, my friend Sarah referred me to a video where a Christian speaker was talking about stillness. In the middle of the video the speaker asked his audience to just stop for five minutes and breathe deeply, rejecting the impulse to follow every thought that entered the brain. As I watched the video, I thought to myself, This must be some type of a joke – does he really expect me to sit in front of my computer for five minutes and be still? Nevertheless, I decided to give it a try. Every time a distracting thought came into my head or I was tempted to check my email, I let it go, focusing on my breath and the Jesus Prayer. It was hard work and I didn’t particularly enjoy those five minutes. However, as it didn’t seem to do any harm, I decided to try it again the next day. For the rest of the week, every day I took five minutes just to be still in the presence of God while breathing deeply.

Gradually—at first imperceptibly—these times of stillness began to increase my capacity for attentiveness. Many of my lifestyle choices up to that point (i.e., giving in to continual distractions and shifts in focus, letting myself be victim of ruminations) had diminished my ability to be attentive, especially to attend to the still small voice of God. I even thought of attention as something outside my control. “After all,” I would often think, “if my brain decides to attend to distractions or toxic thoughts, what can I do?” What Sarah had offered me was invaluable, because it suggested that I did have possible to regain control of my attention. I did not need to be subject to all the disordered thoughts that entered my brain.

I continued to find my attention scattered amid an array of toxic thoughts. But at least I began to realize that I wasn’t completely powerless. By setting aside times to be still, and using those times to intentionally reign in my wandering brain, I found I was able to strengthen my capacity for attentiveness. After doing this for about a week, I began to realize that throughout the day it was becoming a little easier to direct my attention to things that were healthy and life-giving instead of depressing and stress-inducing.

I didn’t get better overnight. Given my continued battle with burnout and chronic exhaustion, well-meaning friends were perfuse in their advice to me. The problem is that various friends were divided in their counsel. One colleague from work, who I will call George, said I was clearly mentally ill and needed immediate psychiatric treatment. Another friend, who I will call Elizabeth, gave the exact opposite advice. “You’ve had a lot to deal with this year, Robin. It’s obvious that your problems have been caused by the difficult circumstances you’ve had to face, not because you’re abnormal or need medication.”

Not knowing who to believe, I decided to consult the experts. I talked to a number of professionals, all of whom shared Elizabeth’s perspective. One person, quoting Viktor Frankl, reminded me that “an abnormal reaction to an abnormal situation is normal behavior.” Notwithstanding, every time I saw George he was relentless and continued to pressure me to find a doctor or psychologist who would refer me for a psychiatric examination. So I visited two psychologists, two professional counselors and a doctor, and none of them would refer me for psychiatric treatment. Instead, they urged me to begin having cognitive behavioral therapy.

Thus it was that I began regular sessions of CBT with a counselor named Samee. Samee was an unassuming woman that was old enough to be my grandmother. Initially, I hoped that Samee might be able to help me change my life. Instead, she offered me something far more valuable: she taught me how to change the perspective I was bringing to my life. Moreover, Samee encouraged me to continue the habit of contemplative breathing and to increase it to ten minutes a day.

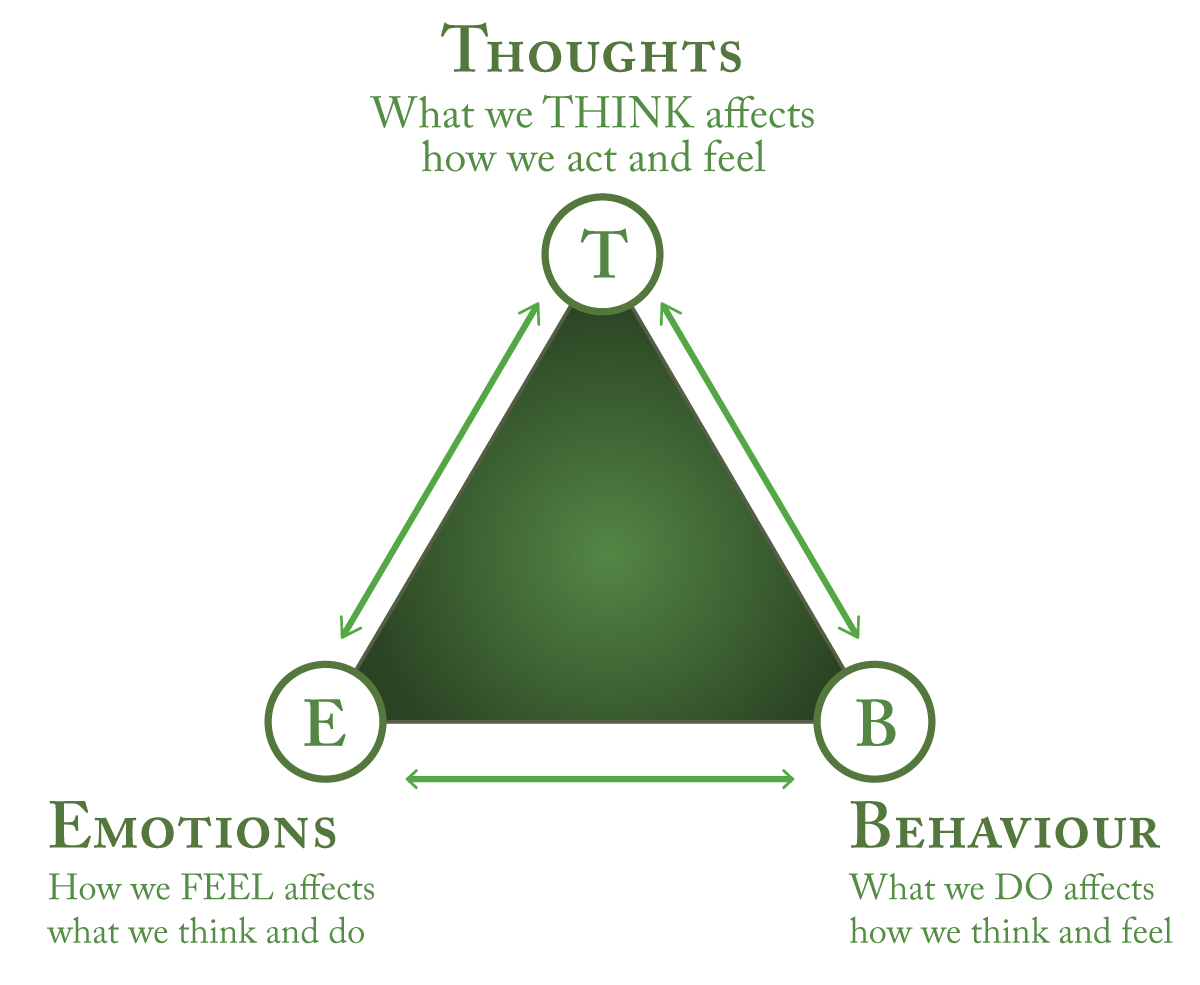

Cognitive behavioral therapy is based on the ancient Christian understanding that there is a web of reciprocities linking how we think with how we behave with how we feel. (For research on ancient Christian approaches to CBT, see Alexis Trader’s book Ancient Christian Wisdom and Aaron Beck’s Cognitive Therapy: A Meeting of Minds ) This is represented by the CBT triangle which has the three points occupied by Thoughts, Emotions and Behavior respectively, with arrows running in all directions.

These arrows indicate that what we think affects how we act and feel, how we feel affects what we think and do, and what we do affects how we think and feel. What happens in many people’s lives is that these interconnections become conduits of toxic spirals: for example, disordered cognitions (a fancy term for bad thoughts) lead to unhealthy emotions and wrong behavior, and the unhealthy emotions feed more disordered thinking and wrong behavior. The purpose of CBT is to reverse this and create healthy spirals. By working to bring a person’s thought-life into alignment with objective reality, and by cultivating rightly ordered behaviors, a person’s troubled emotional life can begin positively to be influenced. We tend to think we have no control over troubled emotions, and often that is often true if we start with the emotions themselves. Often what we need to do instead is to start with the factors that are influencing our emotions, such as our thoughts and behaviors. Troubled emotional states do not arise in a vacuum, but are continually being fashioned by our thoughts and behavior.

A few months into my CBT sessions with Samee, George started pressuring me again to get psychiatric treatment. “If therapy is helping, I’m sure not seeing evidence of it! I think you need to just have the courage to admit that you’re mentally ill and find someone who will refer you for a psychiatric evaluation.” Finally, I made an appointment with a new psychologist, while continuing my sessions with Samee. Unlike the five experts I had consulted earlier, this one agreed: he would refer me for a psychiatrist evaluation and possible treatment.

I reflected on all this as I took the long elevator ride to the top of the building where Dr. Zimmermann practiced. He had better be good, I thought, given that he’s charging me $200 an hour.

After finding my way to the waiting room, I was given paperwork to fill in while I waited for him to become available. After a few minutes I heard a voice calling me, “Dr. Zimmermann will see you now.”

Waiting in the doorway of his office, Dr. Zimmermann greeted me and motioned to sit down. He didn’t seem like a stereotypical psychiatrist, but more like a friendly uncle you would go fishing with. He had a gentle and unassuming manor and wasn’t afraid to make reference to his Christian faith. Even so, Dr. Zimmermann was a little unnerving: as he asked me questions about my life, he seemed capable of reading inside of me and sensing every time I wasn’t being completely honest.

After forty-five minutes of penetrating questions, Dr. Zimmermann looked at me reflectively and said, “The depression and mental burnout you’re experiencing seem like a normal and understandable reaction to what you’ve been through in much the same way that PTSD is normal for those who have experienced the trauma of war. And even though I think your symptoms are non-psychiatric, I could still give you some medication to help you deal with things. But I think you need something better. It’s a simple matter of learning better to pay attention. When you’re in stressful situations, pay attention to what you’re paying attention to. If your attention is hijacked by rumination, or if your thought-life gravitates to negativity, self-pity and anxiety, this will drag you down and your symptoms will become worse. But if your thoughts are filled with peace, gentleness and love, you will feel better and be a positive impact to those around you. Again, pay attention to what you’re paying attention to.”

That simple but profound bit of advice—pay attention to what you’re paying attention to—was worth the $200 I paid him for the appointment.

Is Your Attention under Attack?

Before I visited Dr. Zimmermann, I had done a lot of work on how technologies distract and scatter our attention. After I visited Dr. Zimmermann, I began to realize that perhaps the greatest distraction-machine is not the TV, Facebook, or even the smartphone. The greatest distraction-machine is the human brain itself. Through my reading and conversations with others, I found that the type of negative rumination I had been suffering from is quite common. Many people complain that their brain is like a non-stop radio that won’t turn off however hard they try. This creates stress, which depletes the immune system and uses up valuable resources and energy. Here are some common types of ruminations:

- obsessing over threats to our social needs, including wondering what other people might be thinking about us;

- imagining how we will respond to various future scenarios;

- mentally rehearsing everything we need to do;

- worrying whether our emotional needs are being met;

- focusing on what we will do next instead of paying attention to what we are doing right now;

- replaying in our minds regretful things we said or did;

- thinking about sex, food or finances;

- focusing on everything that is wrong about ourselves or other people;

These types of ruminations wear us down, leaving us with less resources for creativity, prayer, gratitude, empathy and love. Moreover, these types of ruminations often seem to take on a life of their own, as they run through our brain almost involuntarily, disrupting inner-stillness and scattering our ability to focus.

Rumination is rooted in our survival instincts, propelled by the part of the brain that regulates our fight, flight or freeze responses. When we assume (perhaps without even realizing it consciously) that our wellbeing depends on ourselves rather than on God, then we become constantly vigilant to potential threats to our social and emotional wellbeing. Like an animal that continually shifts its focus, scanning its environment for threats, our brain scans our experience for actual or potential problems. Then, as soon as we find a problem, we fixate on it. These types of primordial survival mechanisms are at the center of most stress.

On the other hand, if we truly believe that God is competent to take care of us, and if we truly believe that the hard providences of life are orchestrated for our spiritual benefit, then we can relax in His protective arms. No longer do we need to live from a place of survival and rumination, since we can trust that the Lord is in charge of our wellbeing. We can become like a child who is fully secure in the love of his or her parents.

Attention and Neuroplasticity

As I struggled towards a healthier use of my attention, I was encouraged by discoveries in contemporary neuroscience, many of which are showing that the capacity for attention is like a muscle that grows stronger or weaker based on how we use it.

Scientists use the term “neuroplasticity” to refer to the malleability of our flexible brains. Our brains are not hardwired but soft-wired, since our neuro-connections continually change based on our behaviors, thoughts and emotions. The darker side of neuroplasticity is that researchers have discovered that many of the activities we take for granted as part of our noisy information-saturated culture—activities like multitasking or constant access to technologies that bombard with continual streams of incoming digital stimuli—actually cause the parts of the brain that regulate attention to shrink. But the research also shows that there are things we can do to strengthen the brain’s capacity for attentiveness.

One activity to strengthen your attention is simply to begin focusing on what you’re thinking, feeling and imagining. Whenever you catch your mind going down a certain path, stop and ask, “is this thought drawing me closer to Christ or further away from Him? Is this thought helping me to develop love, forgiveness and inner prayer, or is it increasing my tendency towards anxiety, negativity and rumination?”

Psychologist and author Rick Hanson explained about the importance of this type of meta-attention, suggesting that our very self is continually shaped by what we choose to focus our attention on.

“Moment to moment, the flows of thoughts and feelings, sensations and desires, and conscious and unconscious processes sculpt your nervous system like water gradually carving furrows and eventually gullies on a hillside. Your brain is continually changing its structure. The only question is: Is it for better or worse?

“In particular, because of what’s called ‘experience-dependent neuroplasticity,’ whatever you hold in attention has a special power to change your brain. Attention is like a combination spotlight and vacuum cleaner: it illuminates what it rests upon and then sucks it into your brain – and your self.”

The Ten Most Important Moments of Your Life

It’s time to get more specific about some of the contemplative breathing exercises I found so helpful in my own attentiveness journey. Doing these exercises for just ten minutes every day can be enormously powerful in drawing draw your attention back to the present moment and helping you connect to the peace of Christ. Moreover, because of neuroplasticity, these exercises will help increase your capacity for attentiveness and mental peace, as you literally forge new connections in the brain.

First of all, find somewhere quiet and comfortably, being careful to leave any electronic devices behind. Then start doing some contemplative breathing. Here are four of my favorites types of contemplative breathing. The key is not to get too caught up in specific techniques, but to find whatever works best to connect you with the peace of Christ.

- Five breaths a minute. In this exercise you slow your breath down to five breaths a minute. First you get a clock that you can hear ticking every second, so your ear can keep track of time without having to stare at a device. Then breathe in for four seconds, hold it for another four seconds, and breathe out for four seconds. If you keep doing this for sixty seconds, then you will have gone an entire minute on only five breaths. At the end of the minute you likely won’t feel short of air: in fact, you will feel incredibly revitalized.

- Breathe out the tension. Another breathing technique is to make your exhales longer than your inhales, and as you exhale, visualize all the stress and tension gently leaving your body and soaking into the ground.

- Mindful breathing. Breathe deeply, letting all your attention be focused on your breath—the feel of the air as it enters through your nostrils, the feel of your diaphragm as it fills and contracts. Focusing on your breath like this is a powerful way to tether your attention to your body and hence to the present moment. (Sometimes I will combine this with diffusing essential oils, so the air I’m breathing is sweet and calming.)

- Breath the Jesus Prayer. Try synchronizing your breathing to a prayer such as the ancient Jesus Prayer (“Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me.”) This prayer comfortable fits into the rhythm of gentle inhales and exhales.

The thing to remember is that these techniques are not ends in themselves but simply tools to bring your heart and mind to a place of stillness. On a physiological level, slow breathing does the exact opposite of what happens when your body is hijacked by survival instincts. Perhaps you’ve noticed that whenever you’re confronted by danger, or sometimes when you simply think an anxious thought, the rate of your breathing automatically speeds up. This makes sense: faster breathing is the body’s way of getting ready to fight or flee. But it also works the other way round: when you slow down the pattern of your breath, you send a message to the body that you are safe. Slow breathing helps connect us to the objective reality of our situation, namely that as sons and daughters of God, we really do have nothing to fear. As the Psalmist said, “Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for you are with me; your rod and your staff, they comfort me.” (Psalm 23:4)

By letting our scattered attention rest on our breath, or with a simple prayer that we can synchronize with our breathing, we commit to embrace the safety of stillness. The stillness of slow breathing proclaims that our survival does not depend on following every distracting thought that enters the brain. The stillness involved in contemplative, mindful breathing recalls our wandering minds from the past and the future and tethers it to the present, which is the only place where we can truly be alone with God. Moreover, contemplative breathing is the ultimate assertion that you can relax because God, not yourself, is in charge of your survival. To embrace the stillness of contemplative breathing is to acknowledge that your heavenly Father knows your needs and is taking care of you exactly as He promised.

When I first began doing contemplative breathing for ten minutes a day, it was so difficult, a kind of eat-your-greens type of activity. Moreover, stillness doesn’t always feel safe. Embracing the stillness of slow breathing can be frightening because it removes all the props and distractions that keep us from truly knowing ourselves. As I continued this activity, I found that it began to be liberating. Now it has become the highlight of my day and something it would be hard for me to live without.

If you commit to doing contemplative breathing for ten minutes every day, you may find these ten minutes becoming the most important minutes of your life.

I liked how Hieromonk Maximos Constas described the importance of contemplative breathing in his talks on attention, prayer and distractions.

“If the mind focuses on the breath that means the wandering mind, which has been outside of the body, is now united to the body, and that’s a huge first step, because so often we’re absent from the present moment. You can live your whole life without actually having lived it. Focusing on the breath is important because it brings the mind back to the body, and also because the breath is the one thing that we have that is unambiguously in the present—right where and right now. If I can get my mind to focus on the breath I’m not only entering into my body but I’m also entering into the present. It is so tremendously powerful to be in the present. It can be frightening because it’s a place we’re not familiar with, and I think that’s one of the reasons we run from it. It can be overwhelming.”

Don’t Feed the Monsters!

As soon as a person begins contemplative breathing, they quickly discover that their brain is their own worst enemy. It’s typical to have hundreds of random thoughts arise in your mind, one after another. As this happens, try not to take up the thoughts, but also try not to judge them; just observe. Even if thoughts arise in your brain that aren’t necessarily bad, just observe the thoughts as something outside of yourself and let them go, quietly returning to a place of stillness.

As you begin observing your own thinking in this way, be prepared for a shock. You’ll be surprised to see how much garbage goes through your mind every minute. This is like a person who decides to start watching the food going into his or her mouth. After years of someone eating anything that looks good without ever reading the ingredients, it can be a real eye-opener to start paying attention to what he’s eating. Similarly, once you start paying attention to your own thoughts, you may be horrified to see all the garbage that comes into your brain every minute. When this happens, the temptation is to begin condemning yourself, or judging and arguing with your thoughts, especially those that are toxic. But this is self-defeating. The goal is to simply observe your thoughts as something outside yourself, and to pay attention to your present-moment experience non-judgmentally.

In his book Christ The Eternal Tao, Abbot Damascene explained about the importance of this type of present-moment non-judgmental observations of our thoughts:

“When thoughts come, we should not attempt to get involved or argue with them, for such struggle only binds us to them. As Fr. Sophrony’s Elder, St. Silouan, affirms, “The experience of the Holy Fathers shows various ways of combating intrusive thoughts but it is best of all not to argue with them. The spirit that debates with such a thought will be faced with its steady development, and, bemused by the exchange, will be distracted from remembrance of God, which is exactly what the demons are after—having diverted the spirit from God, they confuse it, and it will not emerge ‘clean.’”…

A thought cannot exist for long under the light of direct, objective observation. If we do not align our will with it, it naturally disappears…. We do not validate the thought by giving it any more attention…. In observing thoughts, we should not focus on them, but rather defocus from them. We should not try to analyze them, for analysis involves us in the very thing from which we are seeking to separate ourselves. Once again, it means we are trusting in our own powers rather than in God’s power. Therefore, we should be simple: just watch the thoughts disappear under the light of observation, as if we were an objective, disinterested spectator; they will pass one by one.”

Abbot Damascene’s point about not attacking disordered thoughts was illustrated with a helpful analogy in Chade-Meng Tan’s book Search Inside Yourself. He compares unwanted thoughts to monsters. If your house happens to get overrun by monsters, you have three choices. Either you can feed the monsters, in which case they will stick around and get bigger. Or you can fight the monsters, in which case you may get clobbered and defeated as the monsters become stronger. Or you can do your best to simply observe the monsters without being drawn into their world. If you choose to ignore the monsters, maybe they will keep sticking around or maybe they will go away; however, it ultimately doesn’t matter, because even if they stick around, you will have learned to treat them with the contempt they deserve. The monsters will have lost their hold over you.

It’s the same way with unwanted thoughts. If we fight unwanted thoughts head-on, then we are focusing on the very thing we want to rid ourselves of, leading to a phenomenon that psychologists have called “ironic process theory” or “the white bear problem.” This problem was described by Fyodor Dostoevsky in his ‘Winter Notes on Summer Impressions’ when he wrote “Try to pose for yourself this task: not to think of a polar bear, and you will see that the cursed thing will come to mind every minute.” Researchers have found that trying to directly suppress unwanted thoughts is about as successful as telling someone not to imagine a polar bear, since the very act of trying not to imagine a white bear inevitably recalls the white bear to mind. Similarly, the very act of struggling against unwanted thoughts is likely to fuel them even more. What tends to work much better is to treat unwanted thoughts with the contempt they deserve, and that means that we don’t feed them and we don’t fight them; instead we simply observe the thoughts as things outside ourselves and gently draw our attention back to where we want it to be.

Peace is Coming

I’d like to close by sharing a message I got from my friend Ruth earlier this year. Ruth is the sister of Sarah, who first introduced me to mindful breathing in the summer of 2015.

Ruth understands the value of breathing in a way most of us do not. The reason Ruth appreciates the beauty of breathing is because she is progressively losing the ability to breathe, as her lungs are being progressively compromised by cystic fibrosis. For Ruth, every breath is becoming an effort. In her email to me, Ruth shared how the constant noise of her oxygen machine, combined with continual breathlessness, makes it a struggle to focus on anything: reading, listening, even having a conversation. Ruth explained how simply getting through each day is becoming more and more of a challenge as she endures the final stages in a protracted process of suffocation.

Faced with such suffering, most of us would simply be struggling for breath. But Ruth shared that she is also struggling for gratitude.

Over the years I’ve talked a lot with Ruth and her husband David about gratitude. Through things they’ve said, but mainly through their example, they’ve helped me to see that it’s possible to strive for peace and gratitude even when everything is going wrong. They have helped me to see that peace and gratitude are not things you either have or don’t have; rather, these are virtues each and every one of us can struggle towards regardless of what is happening in our life. The struggle we face is not to be grateful for extraordinary things that it’s easy to feel thankful for; rather, the struggle is to be grateful for the ordinary things in life that we so often take for granted.

Like breathing.

Breathing, stillness, silence—for those of us who are not struggling with a terminal disease, these gifts are always available to be received with gratitude and joy. Yet often we take these gifts for granted. For Ruth, these blessings are no longer available. Her message to the rest of us is to appreciate the gifts that what we have, even simple things like being able to suck in deep breaths of air.

“I long for people to understand, enjoy and be thankful for the simple blessings they have” Ruth shared in her email with me. But she also shared how so few people are willing to engage with this part of her journey. Sometimes it takes someone who is dying to remind us just how blessed we are for ordinary things in life that we take for granted—things like being able to sit in silence, being able to take a walk with a friend, or being able to withdraw into a quiet room and do nothing but breathe deeply for ten minutes.

I’d like to close by sharing a comment Ruth put on Instagram next to a picture she found meaningful. The picture, which depicts two people walking in the snow with a dog, encapsulates the hushed stillness of a snowy winter afternoon.

“The last few weeks have been hard. Breathing is a struggle and uses enough of my mind to make it difficult to focus properly on anything else. My oxygen flow rate is higher and so the soundtrack to my days is the whistling and blowing of air into my nose. Silence is something I remember but no longer experience. But this isn’t the end. I found this artwork on eBay and love it. It captures my idea of bliss. Winter, the peace and stillness that comes with snow everywhere, walking with my favourite person and our goofy dog through the trees. That has never happened and probably won’t in this lifetime. But it makes me long for the next even more. Pain is not the end. Peace is coming.”