The hero’s journey is a central plot structure in stories—whether film, novels, myth, fairy tales, or ballads—because growing and becoming are central to the human experience. This is reflected in the story of Telemachus in the Odyssey as he matures into a man, or Cinderella’s journey from a small timid girl into a princess, or Ariel’s journey to become human in Disney’s 1989 The Little Mermaid, or Pinocchio’s journey to become a real boy, or Harry’s journey throughout the Harry Potter series into a brave and wise young man.

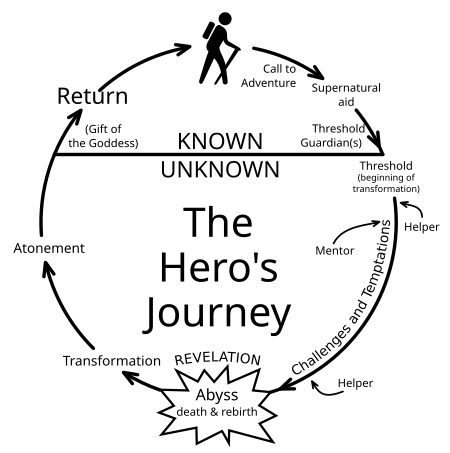

The hero’s journey is more than merely a coming-of-age narrative; it is about growing into maturity and achieving one’s rightful telos. It often begins with a Fall motif—something wrong that must be put right—and usually includes a call to adventure. That call to adventure might be anything from the sight of an enormous beanstalk lately sprung up in the garden, to letters showing up in various places, to a knock on the hobbit hole door. After heeding the call, the protagonist embarks on a journey (whether physical or spiritual, often both) that is usually assisted by a mentor or guide.

The Epimethean: Defying the Machine Through Embodied Living is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The hero typically encounters challenges along the way, including great temptation. To successfully navigate these challenges, he or she will often suffer potential or actual loss for the sake of virtue and love. For example, the cost for Odysseus to secure his rightful wife and lands and restore order to Ithaca is to turn from the possibility of immortality with Kalypso to embrace mortality. In Disney’s 1991 Beauty and the Beast, the beast restores the proper roles of everyone in his castle community only after his sacrifice of releasing Belle and facing death. In Disney’s 1989 The Little Mermaid, Ariel had to sacrifice her voice, and potentially even her freedom, to become human and win the love of Prince Eric. Her father, King Triton, sacrifices himself and his reign to save Ariel, while the prince risks his life to kill the sea witch.

The death motif is often represented in terms of a descent into the abode of the dead in the early stages of one’s redemptive journey, as when Odysseus travelled to Hades to consult Tiresias, or when Gandalf fell into the earth’s cavernous abyss when fighting the balrog, or when Dante began his journey with a descent into Hades. This death journey typically becomes a rite of passage through which the hero is reborn. In The Velveteen Rabbit, there is a literal death as a prelude to becoming real.

If these challenges are navigated successfully, the hero’s journey will culminate in a process of inner transformation and outward recovery, restoration, and resurrection. For example, in Disney’s The Little Mermaid, the sacrifices result in the restoration of order: Ariel’s quest to become human is fulfilled, her relationship with her father becomes rightly-ordered, the human kingdom is able to flourish because Prince Eric is united with his true mate, and the sea kingdom is restored to its rightful sovereign.

The hero’s journey gives coherence to stories about animals no less than humans. It is the story of Simba in The Lion King as he matures into a grown lion, or the rabbit’s journey in The Velveteen Rabbit as he journeys toward becoming real. It is the story of Mole in The Wind in the Willows as the call to adventure leads him from his underground home through a journey from childishness to maturity under the gentle tutelage of Rat and his environs, until he plays a central role in the redemption of Toad Hall.

The hero’s journey is basic to the symbolic imagination because it is the central human story. In the individual life, no less than the collective life of redeemed mankind as a whole, we are on a journey of transformation, leading to the final outworking of our salvation. But our future isn’t fixed since each one of us must ward off temptations that would hold us back, and each of us must navigate obstacles that threaten to keep us stranded in fragility and weakness. In the great myths and tales, these obstacles often take the form of monsters, enchantresses, storms, and temptation.

Each one of us must ward off temptations that would hold us back, and each of us must navigate obstacles that threaten to keep us stranded in fragility and weakness. In the great myths and tales, these obstacles often take the form of monsters, enchantresses, storms, and temptation.

In Disney cartoons, the temptations are often represented musically. For example, when Pinocchio succumbs to the temptations at Pleasure Island, including false mentors that would divert him from his quest to become a real boy, his newfound pseudo-freedom is embodied in the song, “I’ve Got No Strings.” In The Lion King, the song “Hakuna Matata” offers a philosophy that, if accepted, would keep Simba from growing into his true kingly self. In The Little Mermaid, the song “Under the Sea” holds out the temptation for Ariel not to seek the human life but to satisfy her unquiet heart on merely immanent realities.

Villains Reimagined and Heroes Confused

Contemporary cinematography is filled with many wonderful stories—often in the superhero genre—that remain true to the narrative arc of the hero’s journey. But increasingly we are also seeing a plethora of stories that blur the lines between protagonist and antagonist, standing the traditional roles of hero and villain on their head. Viewers have been invited to reimagine iconic villains—including Maleficent, Cruella de Vil, the Joker and, of course, the Wicked Witch of the West—more positively.

The flipside of villain revisionism is confusion about what it means to be a hero. Is a hero someone like Penelope in The Odyssey, who remains faithful to her missing husband at great personal cost, or is it someone like Elizabeth in the 2010 movie Eat, Pray, Love, who leaves her family to go on a journey of self-discovery?

As Hollywood reimagines hero and villain, the narrative arc of the hero’s journey has subtly changed. Rather than the protagonist having to make sacrificial changes to overcome obstacles, the burden of change is placed on the society in which the protagonist’s journey is situated. Consider Disney’s 2021 animated film Encanto.

In this story, it is a little girl, Mirabel, who sees things clearly (and genuinely has a wisdom above her years) while the rest of the adults are ignorant and stuck in their ways. In front of the community, Mirabel denounces her well-meaning grandmother for her unrealistic expectations. Eventually the grandmother realizes that she was being controlled by her fears, comes to understand that Mirabel was correct all along, and apologizes. Mirabel does not have to make any significant sacrifice nor change nor go through the stages of the hero’s journey; instead it is the community around her that must change. (For a longer review of Encanto, see my article “How Disney’s ‘Encanto’ Encourages Weakness, Burdens Children With Adult-Themes, and Promotes A Disordered Relationship With Elders.”

Contemporary cinematography also subverts the hero’s journey by interiorizing the point of tension that longs for resolution, relocating it in the inner landscape of the hero or heroine’s self-doubt, unfulfilled desires, fear of not being understood, anxiety about not fitting in, etc. Viewers can ultimately see the story about themselves; the fall motif becomes vague enough to function as a grab bag into which viewers can project their own issues, with the result that the hero’s victory becomes a mechanism for vicarious self-empowerment.

Story-Telling in the Age of the “New Self”

Behind these revisions of the hero’s journey is a changing conceptual landscape in which personal transformation has been renegotiated under the hegemony of what Carl Trueman calls the “new self.”

Drawing on the work of sociologist and cultural critic Philip Rieff (1922–2006), Trueman contrasts the “old self” and “new self” as competing modes for negotiating the inner landscape. Whereas for the old self, meaning, and thus human flourishing, were rooted in realities external to the individual, the “new self” finds purpose in fulfilling obligations internal to the self, with such obligations assessed primarily through the lens of feeling. The result, Trueman suggests, is “a prioritization of the individual’s inner psychology—we might even say ‘feelings’ or ‘intuitions’—for our sense of who we are and what the purpose of our lives is… Inner psychological convictions [become] absolutely decisive for who they are.” [Carl Trueman, The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self, p. 23]

For this new type of self, authenticity is not found in growing toward maturity or assuming one’s rightful place in structures that are given and received (whether religion, tradition, revelation, morality, or even the structures of received biology), because given structures are taken as an imposition to the individual’s ability to self-construct his or her own reality. Under the reign of the new self, we can still have a process of growing into flourishing, but flourishing is correlated with the undoing of obstacles that would pose any restriction to authenticity, now conceived in terms of radical autonomy.

Under this new framework, the traditional mentor in the hero’s journey becomes merely a reflection of the self. Even if an external person, the mentor merely points the protagonist back to the self-enclosed network of autonomous individualism, through tropes such as “you do you,” or “follow your own song,” or “ignore all the voices around you and just listen to yourself.”

Equally significant, the role of sacrifice in the hero’s journey becomes ambivalent even at the level of personal struggle. In the older tradition, we grow into our true nature through friction and hardship. Accordingly, the hero’s journey involves numerous choices where the hero must turn away from the easy path for a harder road that will result in the character, resilience, and virtues necessary for successful completion of the journey. For example, the majority of the obstacles Odysseus faced on his homeward journey involved the temptation of a life of comfort without struggle. At Circe’s house, the land of the Lotus Eaters, the Sirens, and the Island of Kalypso, the primary temptation was for him to abandon the life of struggle for one of ease. But only through struggle can Odysseus come into the rightful inheritance that is natural to him as a husband, father, and king.

The Teleological Crisis in Modern Story-Telling

To talk about what is “natural” to a character is, of course, to have some idea of his or her proper telos. Crucially, however, one’s natural end is given, nor arbitrarily constructed. In The Wind in the Willows, Toad’s true telos is to grow in the virtues that will enable him to be a good steward of his estate, preserve the inheritance left by his father, and not to bring his loyal friends into disrepute. But to achieve his raison d’etre, Toad must embrace the struggle of self-limitation and virtue-formation. When Toad will not voluntarily embrace this struggle, his three friends forcibly impose limits on him in the hope of helping him reach his natural telos.

For the modern self, virtues that arise after a process of struggle and sacrifice are often perceived as contrived and artificial, and most certainly not natural. Accordingly, the best we can do is be like Elsa in Frozen where the path to redemption lies in learning to “let it go” and be yourself—to realize the authentic person you are inside without sacrifice and struggle, even without the struggle of trying to be good. Significantly, Elsa’s iconic song “Let it Go” associates freedom with lack of struggle. The restrictions of trying to “be the good girl you always have to be” are correlated with repressed feeling (“conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know”) and fear (“and the fears that once controlled me can’t get to me at all”). The solution is an amoral world of freedom – “to test the limits and break through / no right, no wrong, no rules for me / I’m free.”

The song, “Let it Go,” is the complete opposite of Ariel’s “Part of Your World,” and exemplifies the difference between the old self and the new: the latter is about freedom being found in the journey of the unquiet heart toward transcendence, while the former is about freedom being found in self-complacency and the existential burden of self-creation.

Elsa’s choice to let go is not presented as an unmitigated good. As a consequence of her radical autonomy, she inadvertently creates ice monsters and plunges her sister’s kingdom into eternal winter. According to the traditional hero’s journey, one would expect redemption to come through Elsa making a sacrifice, perhaps giving up her abilities to save the kingdom and then receiving her powers back in a resurrected form. Elsa does, in fact, save the kingdom, and her powers do become benign, but not through any sacrifice or virtue, but through “an act of true love” when she hugs her frozen sister. The “act of true love” is a convention taken from prince-princess stories where, as in Disney’s Sleeping Beauty, the prince must be willing to put his life on the line to conquer obstacles before the curse can be undone and the princess resurrected with an act of love. But Elsa does not undergo any sacrifice for the curse to be undone and for her own restoration to be complete.

The 2022 Disney animated film, Turning Red, goes even further than Frozen. While Elsa’s rebellion against “the good girl you always have to be” is tinged with ambiguity, Turning Red unabashedly situates teenage rebellion on the moral high ground. The heroine, a 13-year-old Chinese-Canadian named Mei, goes on a journey toward self-acceptance during the upheavals of puberty. In the process, Mei finds herself clashing with her traditional parents, who run a Chinese temple dedicated to ancestor worship. The conflict between the generations becomes paradigmatic of the internal conflict within Mei, who has to choose between being true to herself vs. submitting to the norms around her. This choice is encapsulated in an opening monologue where Mei states, “Be careful, honoring your parents sounds great, but if you take it too far, you might forget to honor yourself.” Mei’s journey to honor herself involves, not a process toward maturity, but a process of becoming increasingly rude, disobedient and dishonest to her parents, who are portrayed as critical, overbearing, and hypocritical. Ultimately, Mei must come to accept her inner beast. At the conclusion of the movie there is a voiceover with Mei saying, “We’ve all got an inner beast. We’ve all got a messy, loud, weird part of ourselves hidden away. And a lot of us never let it out. But I did. How about you?” This move beast-ward is the true inversion of the hero’s journey. Whereas in Beauty and the Beast, redemption is correlated with the beast (along with the teapot, the mantel clock, etc.) being restored to humanity as the culmination of a journey from self-absorption to maturity, in Turning Red, redemption happens when the human learns to accept the beast within, the culmination of a journey toward greater self-absorption.

Barbie and the Journey of Self-Creation

Perhaps the best example of how the shift between the old self and the new self subverts the hero’s journey is the 2023 box-office phenomenon Barbie.

On one level, this is a story about the longing to be human, in the same genre as Beauty and the Beast, Pinocchio, The Little Mermaid, etc. Although Barbie lives in the pristine and ageless world of Barbie Land, she experiences internal conflict when she discovers both that she is aging and that her unquiet heart longs for something more—longs, in fact, to be human. This is the initial call to adventure that starts her hero’s journey. Barbie’s internal conflict is set against a backdrop of social conflict between the sexes, represented by exaggerated gender stereotypes that play out in tensions between her and Ken. This is the Fall motif in the story that moves toward resolution.

If the narrative followed the hero’s journey, Barbie’s growth to become human would involve making a sacrifice that would result in a restoration of the rightful inheritance, which in this case would be harmony between the sexes in general, and harmony between her and Ken in particular. And in a sense, this is what the movie gives us. After all, Barbie does eventually become human, and this involves the sacrifice of embracing mortality, and thus aging and death. Moreover, the tensions between Barbie and Ken are solved, pointing toward the possibility of harmony between the sexes. In this sense, Barbie preserves key elements of the hero’s journey. Yet it is a “new self” coming-of-age narrative that subverts the hero’s journey in significant ways.

Consider, at the center of the conflict between Barbie and Ken is his longing to share the dream house with her, and to exist in a relationship of interdependence. As he sings, “I wanna know what it’s like to love, to be the real thing.” Barbie not only rejects Ken, but she problematizes his need for her, dismissing his desire to live in interdependence as immature. As Annie Crawford observed in her review of the film for Salvo,

[Barbie] shames him for his longing to have a relationship with her. She shames him for being a man who wants to do things for her and earn her affection, to find his identity and purpose through mutual loving relationship with a woman. Barbie lectures Ken on existentialism and the necessity of defining himself relative only to himself. She asks men to do the impossible: “figure out who you are without me.” While Ken wanted to understand his identity through love, Barbie is committed to total autonomy.

This tension between Ken and Barbie is ultimately solved, but not through love, self-giving, or sacrifice, but through both recognizing they don’t need each other, that each is fully complete and autonomous on their own. While the film seemed to be leading up to a bittersweet ending where Ken loves Barbie enough to let her go like the beast released Belle in Beauty and the Beast, Ken’s final act of letting go involves no sacrifice because he has ceased to need her; rather, his existential redemption occurs through becoming as autonomous as Barbie herself, as embodied in his new t-shirt that reads “I am Kenough.” This self-enclosed independence is the final solution to the disharmony between the sexes that is the film’s leitmotif: each one of us can create our own autonomous reality of self-determination. This quest for total autonomy was the driving force in Barbie’s desire to become human, even at the cost of her own immortality.

Thus, while the story is superficially similar to The Little Mermaid, Pinocchio, and Beauty and the Beast, what drives the protagonist’s final transformation into a real woman is not in a quest for greater reality or transcendence, but the desire for increased self-sovereignty. Again from Crawford:

Ultimately, Barbie chooses to leave Barbie Land for the real world because she wants to be the one who makes meaning, not the thing that is made…. All the movie ends with is a vague gesture toward meaningless female empowerment. To be a woman is to be anything you want to be, which is really to bear the existential burden of perpetually creating and sustaining yourself…In the end, Barbie is the story of Peter Pan and the failure to grow up. Barbie stepped out of a world of exaggerated gender stereotypes and into a world not of sacrificial love for others but of self-centered independence.

Even though Barbie is a Peter Pan story of perpetual immaturity, it still superficially preserves the traditional narrative arc of the hero’s journey. As a result, Barbie’s eventual transformation into a real woman feels hollow, in much the same way as it feels hollow at the end of Frozen when Elsa’s superpowers suddenly become benign.

No Heroism, No Wickedness

Our world is deeply confused about what makes a hero because we are confused about the virtues that constitute heroism. As a result, we not only struggle with the hero’s journey, but we also struggle to understand the antithesis to heroism, namely wickedness.

In the recent film adaption of the 2003 musical Wicked, now the highest-grossing Broadway musical film in the history of cinema, the traditional roles of hero and villain are stood on their head. In this revision of the characters from The Wizard of Oz, Elphaba is no longer an evil antagonist but, rather, a victim whose life is full of moral ambiguity.

Villain origin stories could offer a rich opportunity—following in the tradition of tragedies like Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex—to explore the relationship between nature and nurture, free will and fate, or the relation between dispositional and situational factors in determining character. But that would require an understanding of character, and thus virtue, morality, and ultimately the Good. Given that we are deeply confused about all these elements in the era of the “new self,” the best villain origin stories can do is merely to read things upside down, reversing hero and villain in the classic tradition of Blake’s reading of Paradise Lost. For example, in Wicked, Elphaba (the supposedly “wicked” Witch of the West) is compassionate and has no actual character defects while Galinda (the supposedly “good” Witch of the North) is gossipy, materialistic, self-conscious, and manipulative (traits that become more overt in the musical’s second act). Rather than answering the question musical poses—“Are people born wicked, or do they have wickedness thrust upon them?”—the narrative merely inverts the roles of protagonist and antagonist, making the traditional villain not really all that wicked after all. That is why villain origin stories like Wicked not only fail in telling a good hero story, but fail even to rise to the level of good tragedy.

The moral confusion in Wicked reflects the larger confusion in a society that has lost its way in understanding good and evil, and thus heroism. As Germán Saucedo observed in First Things,

The “sympathetic villain” genre is a symptom of a society that disagrees on what is good and what is evil, or that tries to explain evil away as trauma, psychopathy, or pathology. But to identify and avoid evil, we must first learn to recognize the good. The insistence on subverting villains is a sign we have lost confidence in our belief that we can know what heroism looks like, a heroism that displays the good that would oppose their unrighteousness. In a world without any moral certitude or any agreed upon system to define true virtue, what is wickedness anyhow? It would be just a matter of perspective.

The Power of Story-Telling and the Crisis of Heroism

Ultimately, the hero’s journey is about transcendence, which is why heroes often have a god-like stature. But that transcendence—whether represented by a peasant becoming a princess, a mermaid becoming human, a beast becoming a prince, a human becoming a god, or an ordinary person transcending brokenness and fragmentation to attain wholeness and integrity—is reflective of the primal Story at the center of the universe. As the ultimate Protagonist, Christ inhabited the death-resurrection pattern and then achieved transcendence when He united humanity with divinity at the Ascension.

True hero stories serve as foreshadows or derivations of this primal Story at the heart of the cosmos. When a hero’s journey story is told well, it is deeply true—true to the type of creatures we are, true to the type of world we inhabit, and true to the story of the universe. In the real world, monsters can be defeated, there is always hope, and everyone’s true nature is eventually revealed. In the real world, we discover ourselves, not through a process of self-making but through humility, virtue, and the arts of self-limitation. In the real world, selfishness leads to loss and division but virtue leads to restoration; pride leads to folly but humility leads to wisdom; true love is found not in consuming and devouring but in self-giving and sacrifice. Ultimately, we live in a world where sacrifice leads to redemption and death culminates in resurrection and transcendence.

Good stories provoke emotional sympathy with these rightly-ordered patterns, and often more effectively than mere didactic instruction, for they can navigate past the mental roadblocks that might otherwise stand in the way of heartfelt resonance with the Good. But conversely, a story can provoke an unconscious sympathy with what is disordered. When stories subvert the hero’s journey pattern, they are deeply untrue and malform our emotions—especially the emotions of children—in a type of reverse catechesis.

We understand the world and ourselves through stories, and we become the stories we tell and love. Ultimately, stories help each of us answer the questions that are crucial to our own hero’s journey. What does flourishing look like? What am I being called to sacrifice in order to bring about a better world? Who are the true mentors in my life? How can I become truly human? If we are to navigate these questions with wisdom and virtue, we need good stories. And that means recovering the power of the hero’s journey.

This post originally appeared on my Substack and is republished here with the generous permission of the author, namely me.