This article forms part of an ongoing series aimed to equip students at classical schools with the skills needed to research for their senior thesis. To read the introduction to the series click here. To access all articles in this series, click here.

Two Kinds of Knowledge

In his biography of Dr. Johnson, Boswell tells of a time they visited a friend. Retiring to one side of the room, Dr. Johnson began pouring over the backs of books on the shelf. This prompted Boswell to remark to a certain Sir Joshua, “He runs to the books as I do to the pictures: but I have the advantage. I can see much more of the pictures than he can of the books.”

Another man joined in the conversation and observed, “But it seems odd, that one should have such a desire to look at the backs of books.”

Hearing their remarks, Johnson replied with characteristic sagacity, “Sir, the reason is very plain. Knowledge is of two kinds. We know a subject ourselves, or we know where we can find information upon it. When we inquire into any subject, the first thing we have to do is to know what books have treated of it. This leads us to look at catalogues, and the backs of books in libraries.”

The type of knowledge that Dr. Johnson was talking about–knowledge of where and how to find information–is part of what is meant by the term “information literacy.” This article is about one aspect of information literacy, namely how to find information online when you are researching for your senior thesis.

But…Don’t I Already Know How to Find Information Online?

Most of us think we’re already pretty adept at finding information on the internet. Moreover, we don’t usually think of online information retrieval as a skill that we can refine, practice, and get better at.

I was no exception to this. In 2004, when I was fresh out of college and living in England, I saw that a political action group was advertising for an “online researcher.” I thought, “I could do that – after all, I’m pretty handy at finding information online.” So I applied for the job and was accepted. For the next nine years, with only a one-year hiatus to teach history at a private high school, I worked as an official “researcher” for this organization. Yet surprisingly, I never gave much thought to how I was researching. For me, research was putting a search query into Google and skimming whatever results came up until I found something that seemed useful. If I was really serious about the research, I might check the second or third page of search results.

Gradually, I developed an intuitive sense of which type of websites I could trust and which I could not. Yet I wouldn’t have been able to explain that to another person. Moreover, as the dark side of the internet became more sophisticated in the first decade of the twentieth-century, fake news websites began simulating the look and feel of genuine websites. Once I was taken in by a fake news story, which I almost put in our magazine before my editor spotted the mistake.

Later, when I pursued a Master’s degree in history from King’s College London, I engaged in more sophisticated research techniques using scholarly books and journal articles. Yet even so, when researching online, little changed in my approach of googling. (And yes, Google is now an official verb as well as a proper noun. In its verb form, the G is not capitalized.) And even though my Master’s at KCL was an official “research degree,” no one at the university actually trained me in basic research techniques.

My experience is not unique. Most of us think we have a pretty good knack for separating the wheat from the chaff, although we couldn’t really explain this process to someone else. For most of us, when we think of online research, we simply mean typing (or speaking) a question or a couple keywords into a search engine, and then seeing what comes up. Some of the results will include links to other pages, enabling us to “browse.”

Actually, there is nothing wrong with this approach, especially for quickly gaining entry-level knowledge of the popular discourse surrounding a topic or question. However, for doing serious research, such as working on your senior thesis, getting information for business purposes, or finding the truth on a contentious and complicated subject, something more is needed than simply googling.

I became interested in best practices for online research in 2019, when I began pursuing a Master’s in Information and Library Science through the University of Oklahoma. I had begun pursuing this degree because I hoped to become a reference librarian at an academic library. I envisioned that working at a library would be a great opportunity to combine my passion for books with my love for helping people. But I quickly found that library work is less about books than you might think. Most of a library’s resources are now online, rather than on the shelves. This means that a key part of a librarian’s training is focused around online information retrieval. As I began studying best practices for finding information online, I realized how limited my earlier toolbox of retrieval techniques had been.

Through my studies at the University of Oklahoma, I began to develop a toolbox of simple but effective techniques that might have saved me dozens of hours if I had known about them earlier. I often compare these techniques to screwdrivers. The difference between researching online with best practices vs. researching online in a hit-and-miss way is like the difference between a manual screwdriver and an electric screwdriver. Anything you can do with an electric screwdriver can also be done with a regular screwdriver, but it might take you three or four times as long.

As I began to learn the best practices for finding information online, the thing that impressed me was how simple most of these techniques actually are. These are not the types of techniques a person needs a Master’s in Information and Library Science to know. In fact, many of these information retrieval tricks are simple enough for children to learn.

So why doesn’t everyone know about these techniques? Part of the answer is that our school systems spend an inordinate amount of time imparting knowledge to students while spending comparatively little time on knowledge-acquisition skills. This is like giving someone an abundance of fish but never teaching them how to bait, cast, and reel.

This emphasis on finding information online should not deny the importance of reading books. I take it for granted that anyone researching for their senior thesis will be reading relevant books on their chosen field. However, finding the best books, locating reviews, learning how key books are integrated into the discourse on a subject – this will all largely depend on your competency as an online researcher. Just as there are skills necessary for being a strong reader – skills like focus, patience, and attentiveness – so there are skills involved in finding, evaluating, and using information from the internet.

But what is the internet?

What is the Internet?

Most of us think we know the answer to this question. Our conception of the internet usually goes something like this: “the internet is what you access when you type (or speak) a search query into Google, or some other search engine.” Some of us might give a more sophisticated answer, perhaps noting, “The internet is the vast web of interconnected computer networks, available to anyone who has an internet connection.”

These answers are only half correct. The reality is that all the websites that are publicly available on “the net” or “the web” are one part of the internet. But there is a second part of the internet, and it’s this second part that is crucial for researchers.

This second part of the internet is known by various names, including the “deep web,” the “licensed web,” and the “proprietary web.” Whatever you choose to call it, this is the part of the internet that includes all the online journals, databases, and scholarly publications that form the backbone of academic research, and which you can typically only access through university libraries.

Here’s a basic definition of these two parts of the internet:

- The Open Web = everything that is publicly available online.

- The Licensed or Proprietary Web = the part of the internet that can only be accessed by fee-paying institutions.

This is a distinction I discuss further in my tutorial video below.

How Does the Licensed Web Work?

Most of us know how the open web works, at least from the user’s perspective. But how exactly does the licensed web work?

The best way to answer this question is to take a fictional example.

Professor Tilby has spent the last year and a half in the jungles of Madagascar studying how a spider, known as Darwin’s bark spider, is able to create webs that can span up to 25 meters (these spiders can really do this, by the way, even though Dr. Tilby is fictional).

When Dr. Tilby is ready to publish his article on the spiders, he sends it to the scholarly journal, Academic Biology. After a process of peer review in which the journal’s team of scientists check over Dr Tilby’s work, the editors decide to publish his piece in their Spring edition.

It costs money to produce Academic Biology, just like it costs money to publish a book. Thus, the publishers of the journal do not just make their issues available for free. Instead, they sell subscriptions to libraries. Many academic libraries (the libraries attached to colleges and universities) subscribe to this journal. Of these universities, some subscribe to the print version of the journal, but most save shelf space by simply buying electronic access.

As soon as the Spring edition of Academic Biology comes out, Dr. Tilby’s article is automatically accessible to those libraries that have digital subscriptions to the journal. This means that his article can be accessed from any computer terminal in these libraries. The journal can also be accessed by students and faculty who have login credentials for remotely accessing the library’s online resources.

Now what is true of the journal Academic Biology is also true for tens of thousands of online resources that university libraries subscribe to: these resources are not available to the public, but can only be accessed from the computers at the library, or by members of the university who have remote login access (typically all faculty and students). Many scholarly journals are available on the open web, and this is called “open access,” but most are not.

Now suppose you are considering writing your senior thesis about the webs produced by Darwin’s bark spider. You’ve read on Wikipedia that the bark spider’s webs are “the toughest biological material ever studied” and “ten times tougher than a similarly-sized piece of Kevlar” (a strong synthetic fiber used as a replacement for steel in racing tires). Intrigued, you want to learn more. Dr. Tilby’s research would actually be very useful to you at this point. The problem is that you don’t know that a spider scientist named Dr. Tilby exists, and you don’t know that his article has just been published in the Spring edition of Academic Biology. You could spend hours on Google, but Dr. Tilby’s article would still not come up because it is not part of the open web; it belongs to the proprietary part of the web that universities pay to access. If you were lucky, you might find a reference to the title of his article somewhere on the web, and maybe even an abstract of it, but the entire article would not be available for free.

To access Dr. Tilby’s article you would need to go into a library that has an electronic subscription to Academic Biology. Once in the library, you could access the article from one of their terminals. Depending on how their subscription is set up, you might even be able to download the article as a pdf and save it to your Google jump drive, or a flash drive.

But…we are getting ahead of ourselves. Remember, you don’t even know that Dr. Tilby’s article exists. So how are you going to find out about it, let alone find out which university libraries have access to it?

Here we must learn about another important thing about academic libraries that is crucial for a researcher. Just as there are search engines like Google that search the open web, so there are also search engines that comb through the licensed web. These are called databases and they are usually subject-specific.

For example, there are databases for searching the licensed web in biology, history, business, education– you name it. In addition to subscribing to journals, university libraries pay large fees to subscribe to these various databases to help researchers get connected to the journal articles they need. (Sometimes it can get more complicated, as some publishers of content double duty as database publishers, while some databases give full text access and others merely share abstracts, but these are details that need not concern us here.)

Here is a tutorial video where I introduce students to some of the most common databases.

Now let’s put all of this together to see what it looks like in practice.

You walk into a university library and go up to the reference desk. At the reference desk you explain to the librarian that you are looking for information on Darwin’s bark spider. (Don’t be afraid to ask for help—reference librarians love helping people.) The reference librarian can then point you to the right database, perhaps even helping you in the search. By searching through the database, you would likely come across Dr. Tilby’s article, and many other helpful resources.

The same applies for any research project: an academic library will have access to a wealth of resources that are unavailable to the open web and unavailable to most public libraries. Anyone can use the resources in an academic library, even if you are not a student of that university. While you would not be able to check out books without being a member of the university, you can often download journal articles as pdfs and email them to yourself using one of the library’s computers. Many libraries also let you save proprietary articles onto a flash drive, or print them.

Let’s review everything we’ve learned so far.

- The internet is not one place but two: (1) the open web that is available to anyone with an internet connection; (2) the licensed web where content is made available to fee-paying institutions.

- Most published research is never put on the open web, but is part of the licensed web available on a subscription basis.

- University libraries pay to subscribe to many journals on the licensed web, as well as subject-specific databases that search these journals or aggregate journal repositories.

- When going into a library to research, your first stop should always be the reference desk. The librarian at the reference desk will be able to help point you to the right database, or some other resource. Bring a flash drive.

Why Scholarly Publications Are Important for Researchers

At this point, you may be wondering, “Why would I want to go into a library to do research? Isn’t the open web good enough?”

Sometimes the open web is good enough, which is why the next article in this series will be entirely devoted to techniques for searching the open web. But remember the example of Dr. Tilby: his article went through a process of peer review before it was accepted by Academic Biology. Most of the articles on the proprietary web have gone through a process of peer review before being accepted for publication. This means that other experts in the field reviewed Dr. Tilby’s research before giving the green light for publication. Nearly all the scholarly journal articles on the licensed web have gone through a similar process of peer review.

So that is Reason #1 that academic journals are important for researchers: they have been written by experts and have been reviewed by scholars prior to publication.

It is just as important to emphasize what this does not mean. This does not mean that all the articles on the licensed web are trustworthy, let alone that they are free from bias. In fact, many articles on the licensed web have been discredited, while some articles contradict other articles. In the licensed web you will be exposed to a wide range of viewpoints that require critical thinking, but those viewpoints are within the realm of what we call “scholarly.” Again, by “scholarly” we mean that the articles have been written by experts (usually professors or professional researchers) within a given field, and reviewed by their peers prior to publication. If you are writing a paper and your teacher asks you to cite “two journal articles,” it is these types of scholarly publications that the teacher is referring to.

Another reason that scholarly publications are important is that the authors will usually use footnotes to reference their claims and quotations. Following these footnotes can be a rewarding task for the researcher, pointing you towards other sources to track down within the licensed web. This is the scholarly equivalent to browsing through hyperlinks on the open web.

This is Reason #2 that scholarly journals are important for researchers: they are a portal to additional research.

If you are doing research in the humanities, footnotes can be particularly useful in tracking down the original source for quotations or references. The open web contains numerous quotations that are mis-attributed to historical figures, but which have been repeated so frequently that millions of people (including authors of books) have come to believe that so-and-so said such-and-such. One example is the famous quotation that is routinely attributed to Edmund Burke, “All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.”

This quotation has been attributed to Burke thousands of times, but if you read through his entire corpus, including his letters, you won’t find it. The quote actually comes from John Stuart Mill, who noted in an address at the University of St. Andrew on February 1867, “Bad men need nothing more to compass their ends, than that good men should look on and do nothing.”

Here is a tutorial video where I discuss the importance of using scholarly publications in your research.

Leveraging Someone Else’s Literature Review

Another reason that scholarly or “peer-reviewed” articles can be useful for researchers is that most of them begin with some type of literature review. That is, the author will survey the existing scholarship in the field before advancing a new claim or theory. By paying close attention to the sources the author refers to, both in the literature review and in the bibliography at the end of the paper, you can get a good idea of the wider scholarly discussion surrounding the particular issue. If you are wanting to become familiar with the literature on a given topic, piggybacking off someone else’s literature review can save you hours and hours of time. If you are writing a paper, showing familiarity with the literature on a topic will greatly help your credibility. Moreover, as you review the literature, you may find that ideas that you thought were original to you have already been advanced by scholars in the field. This has happened to me many times. Then, instead of reinventing the wheel, you can work to improve the wheel.

Keep in mind that most of the time a high school student goes online to do “research,” he or she is only researching in a qualified sense. Even when researching for the senior thesis, what the student is really doing is accessing the research that other people have conducted and published. Even when you have something original to contribute to a field (for example, by organizing material in a new way or providing a new interpretation of something), you will likely be building on scholarship that has already been done. Thus, the more familiarity you have with existing literature, the better your own research will be.

This is Reason #3 that academic journals are important for researchers: by attending to an article’s literature review, you can become informed on a subject quickly and save hundreds of hours.

As an example of a typical literature review, consider an article that was published by the journal Computers in Human Behavior in 2016, titled “The relationship between metacognitive experiences and learning: Is there a difference between digital and non-digital study media?” I came across this article a few years ago when I was researching to see if there were differences in learning outcomes between students who read material from a screen vs. students who read physical materials. The article begins with the following literature review on the subject:

“In today’s society there is an increased use of digital equipment, with PC’s and tablet devices now being used more frequently also in educational settings. This has opened up new ways of learning, both at an individual level but also at a group level. For instance, there is currently a large interest in the development of collaborative e-learning environments and multidisciplinary learning groups (e.g., Dascalua, Bodea, Lytras, Ordoñez de Pablos, & Burlacua, 2014), and technology is also seen as an important element of knowledge management (e.g., Zhao & Ordóñez de Pablos, 2011). This development calls for more knowledge about if and to what extent cognition is influenced by digital versus non-digital presentation format (Carr, 2010). In an educational context, digitalization has resulted in an increased emphasis on students’ digital competence. In parallel, there is an additional focus in today’s schools on students’ ability to engage in self-regulation, defined as the extent to which the learner is “metacognitively, motivationally and behaviourally active participants in their own learning process” (Zimmerman, 1986, p. 308). The combined focus on digital competence and self-regulation necessitates more knowledge about the relationship between learning and self-regulation in digital compared to traditional paper-based learning.”

Notice that this paragraph cites five sources. The next three paragraphs in the article are also part of the literature review and continue surveying the landscape of scholarship on this issue. Based on the description of these articles, I was able to get a quick idea of which articles I wanted to track down and read for myself. The same would be true for any topic one might be researching: most scholarly articles will start off by reviewing the current literature on that topic. This is a quick way to come up to scratch on a topic.

But be careful when piggybacking off someone else’s literature review. As a high school student, it can be tempting to simply cite an article without actually looking it up for yourself. But scholars do not always accurately represent their sources, or they may cite something in a misleading way. For example, in the above literature review, the authors cite Nicholas Carr’s 2010 work. From the article’s bibliography I learn that this is a reference to Carr’s book The Shallows: What the internet is doing to our brains. Let’s look again at this brief description in the literature review. “This development calls for more knowledge about if and to what extent cognition is influenced by digital versus non-digital presentation format (Carr, 2010).” Based on this description, we might think that the purpose of Carr’s book is to call for more research, perhaps lamenting the lack of research in this field. But in fact, Carr’s book The Shallows argues that there is already a substantial body of research available on how cognition is influenced by the format. Although their description of Carr’s book is technically correct, it gives a misleading impression concerning the book’s topic and scope. So always look sources up for yourself before referring to them.

Another thing to be careful about is not assuming that a literature review reflects the most recent scholarship on a question. An article that was published a few years ago may offer an accurate summary of the current state of scholarship that persisted at the time the article was published, but it obviously cannot take into account everything published since then. Also, there may have been further research to discredit the article you are reading, and there may even have been retractions. So cross-check what you find with other articles, especially recent ones.

Let’s summarize what we have seen so far.

- Journal articles from the licensed web are particularly useful if they start off with a literature review.

- By attending to references and citations, including those given in a literature review, you can find out about other relevant literature in the given field. This can save an enormous amount of time.

- Always check references for yourself.

More About Research Databases

As we have already seen, much of this research is aggregated into subject-specific databases. Here are some popular databases.

- PsycINFO. Covers psychology and related disciplines in the behavioral sciences. Materials indexed include journals, book chapters, books, and dissertations. Some full text available.

- Academic Search Premier. A powerful database covering social sciences, humanities, education, physical and life sciences, and ethnic studies.

- ERIC. A database covering education.

- Alexander Street. A database aggregating various videos and documentaries.

- Library Literature & Information Science. A database for research in library science.

- ARTstor. A database that stores over two million images that include collections from a wide variety of civilizations, time-periods, and media.

- ABI/INFORM Trade & Industry. Provides in-depth news and analysis of industry trends, companies, products, executives, and developments through over 4000 sources including journals, market reports, industry reports, magazines, and newspapers. Major industries covered include telecommunications, computing, transportation, construction, petrochemicals, food & drink, pharmacy, insurance, and finance.

- PubMed. Provides access to the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) digital archive of biomedical and life sciences journal literature. Some full text available.

- Web of Science. Multidisciplinary index covering topics in the sciences, social sciences and humanities. It is the electronic equivalent of the Arts & Humanities Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index, and Science Citation Index. Some full text available.

- GeoRef. International database of geoscience literature of the world. Materials indexed include journal articles, books, maps, conference papers, reports and theses. Covers the geology of North America from 1785 to the present and the geology of the rest of the world from 1933 to the present. The database includes references to all publications of the U.S. Geological Survey. It is the electronic equivalent to Bibliography and Index of Geology.

- HistoricalAbstracts. Covers the history of the world from 1450 to the present. Materials indexed include abstracts to books, journals, and dissertations.

Each of these databases includes a wealth of information, and we could spend pages discussing their features. And these are only a handful of the hundreds of databases that are available.

It’s important to understand that the techniques for searching research databases are different to the techniques we use in search engines like Google or Bing. Although the structure and vocabulary of databases may seem confusing, with a little practice they can easily be mastered. Once you know how to use databases, you will find that for many types of searches they are actually easier than searching on Google. The first thing you need to know is the difference between keywords and subject terms.

The Difference Between Keywords and Subject Terms

Databases do not use natural language searching like Google does. Instead, you have to know exactly the right vocabulary to use. Articles are indexed in databases according to subject terms. Subject terms are terms that the database assigns to a source to describe what it is about. Sometimes called “descriptors,” these are the words the database uses to index its content. Often these are terms you wouldn’t have thought of yourself because each database has its own controlled vocabulary or jargon to describe the topics covered in articles. A list of these subject terms sometimes appears near the article’s abstract, and sometimes at the end of the article.

For example, the geology database GeoRef has information on a 1988 article ‘Earthquake hazard in Jordan,’ which used historic data to try to predict the type of earthquakes that could be expected in the Kingdom of Jordan. Here are the subject terms (or “descriptors,” as they are called in this particular database) associated with this particular article:

- Asia;

- Dead Sea;

- Dead Sea earthquake 1202;

- Dead Sea earthquake 658;

- earthquakes;

- engineering geology;

- faults;

- geologic hazards;

- Hauran earthquake 1151;

- Hauran earthquake 1182;

- history;

- Jericho earthquake 1160;

- Jericho earthquake 1250 BC;

- Jericho earthquake 1546;

- Jericho earthquake 1927;

- Jericho earthquake 31 BC;

- Jericho earthquake 746;

- Jordan;

- Jordan Valley earthquake 1973;

- Karak earthquake 1834;

- Karak earthquake 2150 BC;

- Karak earthquake 362;

- magnitude;

- Middle East;

- modified Mercalli scale;

- probability;

- Safed earthquake 1759;

- Safed earthquake 1837;

- Safed earthquake 419;

- Safed earthquake 759 BC;

- seismic intensity;

- seismology;

- statistical analysis;

- strong motion;

These subject terms are not the same thing as a keyword. A keyword is any term you use in a search. It could be the type of media you are searching (e.g., video, book, magazine), or phrases that might appear in the content of the article. Keywords are what we use when we search with Google, or when we perform natural language searching. Keywords have not been predefined like subject terms have, and thus they tend to lack the specificity of subject terms. For example, if you remembered reading part of a sentence in an article but couldn’t remember the title, that sentence fragment would be a keyword or key-term. By contrast, “subject terms” or “descriptors,” such as those in the above list from GeoRef, are the controlled vocabulary of a particular database that serve the purpose of linking similar pieces of information.

The cash-value of subject terms within the information retrieval process is that they can form the basis for a new search. Unless you are a specialist in a certain field, it may not be immediately apparent which terms the database indexes articles under. For example, you might spend hours searching for “thirteenth-century earthquake in the Dead Sea,” when you really need to search “Dead Sea earthquake 1202.” You might be searching for PTSD when the articles you need are indexed under “post traumatic stress disorder.” By becoming familiar with the controlled vocabulary of a particular database, you can execute searches with more efficiency.

When Leah was working on her senior thesis, she was trying to find articles on journalistic integrity in the digital age. She searched and searched and couldn’t find anything. Finally, she found one article that seemed relevant, and when she looked at the subject terms she saw that it was indexed under “journalistic ethics,” among other things. Once Leah became aware that this type of article is indexed under “journalistic ethics,” she was able to conduct a new search using this subject term and found numerous other helpful articles. Some databases have a thesaurus function to help the researcher become familiar with the database’s controlled vocabulary. The researcher will put a term like “journalistic integrity” into the thesaurus, and it will return the subject terms corresponding to that, such as “journalistic ethics.”

Let’s take another example to understand the difference between keywords and subject terms. In 2017, a learning company hired me to research the effectiveness of using mindfulness practices in the classroom. At the time, I didn’t have access to the ERIC database, which is the largest source for information on education. But now I do have access to ERIC and I want to review what scholarship has been published since 2017. Yet all I can think to search is “mindfulness AND classroom.” These are keywords and they will retrieve all articles that are about both mindfulness and classrooms. (Had I searched “mindfulness OR classroom,” then the search would have been even broader, bringing up results that have either of these subject terms but not necessarily both.) This is very broad, but it is still a good place to start because if I find even one highly relevant article, then I can review the subject terms and incorporate that into my next search.

So I put this search into the ERIC database. After browsing the results, I found one that is very relevant to my needs, a paper published in 2019 by the journal Beyond Behavior. Sure enough, ERIC gives the following list of subject terms (or “descriptors,” as they happen to be called in the ERIC database).

- Student Behavior,

- Behavior Problems,

- Behavior Modification,

- Emotional Problems,

- Metacognition,

- Perception,

- Teacher Role,

- Classroom Techniques,

- Intervention,

- Human Body,

- Physiology,

- Elementary Secondary Education

These terms, or some of them at least, can be useful in forming my new search.

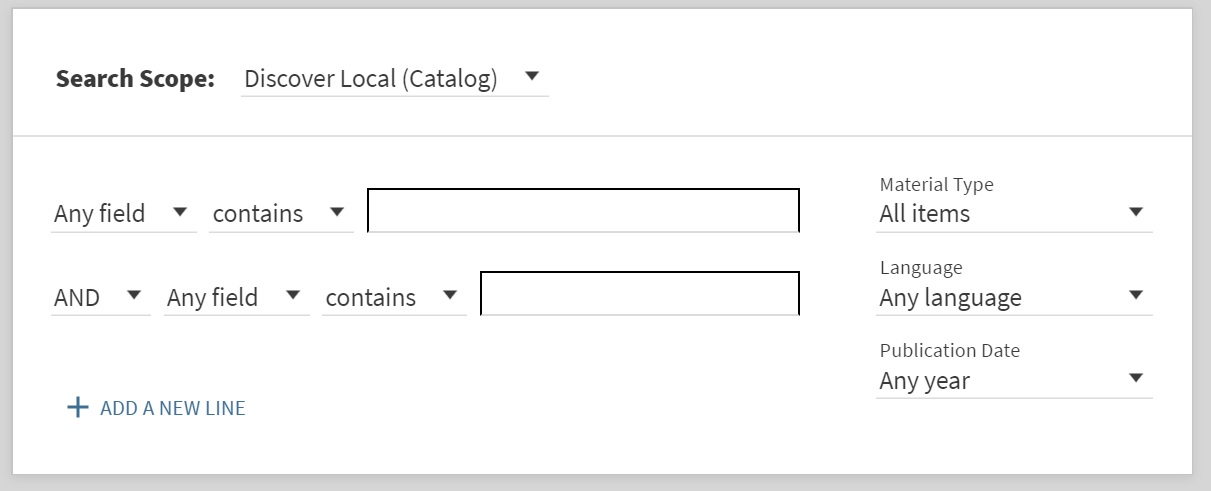

Most databases have fields that enable you carefully to distinguish between subject terms and keywords. For example, on the website for the University of Oklahoma Libraries, they give you the option of having one search field for subject terms, and another field for putting in keywords or other types of information.

Google is Your Friend

But what if you can’t get into a library to check their databases? That’s where Google comes in handy. Google is a powerful research tool, but only if you know how to use it wisely. That will be the topic of our next article in this series.

Further Reading