In an earlier article I explored how some high school teachers are abandoning writing as a teachable skill. Why require students to master the craft of essay writing when ChatGPT can produce content so much better? I responded to that question by offering some reasons why it would be disastrous to abandon the craft of writing in high school.

But given that ChatGPT should not be used as a substitute for high school writing, does it follow that it has no place in the classroom? What about using AI as a research tool? Those who are involved in Christian schools (whether day schools or homeschools) may be particularly curious whether there is value in using chatbots for information retrieval. Is ChatGPT simply the contemporary equivalent to an encyclopedia or database, or should it be completely eschewed?

Currently such questions are hypothetical because ChatGPT is not very accurate in providing factual data. But if chatbots ever achieve high levels of factual accuracy, we may begin to think that consulting them is no different from consulting Wikipedia. Is that okay?

To address this question, let’s begin by taking stock of the larger philosophical landscape.

Present Epistemological Challenges

Our culture is currently undergoing an epistemological crisis. Having access to so much information, it is increasingly difficult to separate the wheat from the chaff, let alone differentiate between information, misinformation, and disinformation. While greater access to information has led to more knowledge, it has not led to greater wisdom. In fact, the current glut of information has resulted in widespread confusion. Amid so many competing voices, many are completely giving up on objective knowledge and lapsing into some form of post-truth epistemology, whether relativism, skepticism, cynicism, or hive-mindedness.

We are, in fact, quickly approaching the situation described by former KGB spy, Yuri Alexandrovich Bezmenov, when he spoke with G. Edward Griffin in a now-classic 1984 interview. Bezmenov described a key strategy the Soviets used for psychological warfare, designed to demoralize a population until they begin to internalize lies.

Exposure to true information does not matter anymore. A person who was demoralized is unable to assess true information. The facts tell nothing to him. Even if I shower him with information, with authentic proof, with documents, with pictures … he will refuse to believe it, until he is going to receive a kick in his fat bottom. When the military boot crashes his balls, then he will understand, but not before that. That is the tragedy of the situation of demoralization.

We do not yet live in the type of military dictatorship Bezmenov feared, but we are quickly approaching demoralization. One primary reason for demoralization is that we are bombarded with more information than we can assimilate. Amid so many competing voices, can we even know what’s true anymore? Is it even possible, let alone practical, to perform objective due diligence on all the information claims we encounter?

For many, the answer to this last question is no, at least according to what I found in a series of interviews from 2020 to 2021. I discovered that even conservative Christians are giving up on the possibility of objective research, and instead adopting various tropes that have become paradigmatic of our post-truth moment, including, “it all comes down to who you choose to believe,” or “see if it feels right” or “the difference between real news and fake news is just a point of view.”

Into this state of affairs enters generative pre-trained transformers. It is not hard to see how these epistemological problems are about to be intensified. Soon every ideological tribe may have their own version of ChatGPT. One chatbot customized for Republicans, one for Democrats, another for Catholics, evangelicals, Muslims, hippies, crunchy moms – you name it. Everyone can enjoy information exactly customized to his or her own preferences.

This is the situation we are quickly approaching, and it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see that this will only intensify the existing epistemological challenges. Faced with so many conflicting information sources, can we even know what’s true anymore? Or will we merely collapse into the type of demoralization that Bezmenov warned about where the only information we can take seriously is a military boot crashing our fat bottoms?

The Solution to the Epistemological Crisis

Thankfully there is a solution to the looming epistemic disaster, and it’s called information literacy.

The term “information literacy” emerged in the 1970s among scholars working in Library and Information Science. It refers to the skills, dispositions, and habits constitutive to sound judgment when retrieving and working with information. In digital contexts, to be information literate is to possess practical competencies at retrieving, understanding, evaluating, and working with information. As with other forms of literacy (i.e. reading literacy, financial literacy, etc.), the term can refer both to an academic domain studying a certain phenomena, as well as to skills that are taught.

You may never have heard of information literacy. Even if your children go to Christian schools, college prep schools, charter schools, or classical schools, there is a good chance they have never been taught information literacy. I don’t know why this is, but most of the time when teachers require students to undertake research projects (for example, a senior thesis), they often just say, “Go research,” without ever giving students the skills for how to be a good researcher. As a result, students attending some of the best high schools in our nation are often unable to answer basic questions like the following:

- How do you know if a website is reliable?

- What steps would you perform when conducting due diligence on an information claim?

- What are some digital tools you could use for verifying or falsifying contested information claims?

- What type of information-needs are best suited for an internet inquiry and which type are more suited for books?

- What are some methods for setting up an effective Google search, and how does this differ from search strategies appropriate for academic databases?

Lacking these information literacy skills, students become susceptible to demoralization, relativism, cynicism, radical skepticism, emotivism, hive-mindedness, etc.

If lack of attention to information literacy is a problem now, it will be intensified ten-fold after AI-based research methods have become the primary digital retrieval tool in the developed world.

The solution I have put forward—teach information literacy—comes with a hard pill that many AI-skeptical Christian teachers will understandably find difficult to swallow. For it means actually bringing ChatGPT into the classroom.

Teach Information Literacy Using ChatGPT

Very soon the Google search will likely be replaced by more powerful AI-powered information delivery systems. AI may become so adroit at delivering desired content and images (if not entire websites immediately generated for the customized needs of a single user) that surfing the web will become a thing of the past. The very ease with which pre-packaged customized information will be delivered to each user makes it imperative that students receive AI-based information literacy instruction.

Since most students will soon be using AI information-retrieval systems outside the classroom, it behooves Christian teachers to teach their students to approach these systems with wisdom, similar to how Christian educators teach students to think critically about popular music or the smartphone. Here we may draw on the wisdom of C.S. Lewis who remarked, “Good philosophy must exist, if for no other reason, because bad philosophy needs to be answered.” Similarly, good habits for using AI must be taught if for no other reason than bad habits must be addressed and mitigated.

What might this type of AI-based information literacy instruction look like? Though AI is still in its infancy and will likely pose challenges we cannot currently foresee, I will venture to suggest four areas where Christian educators can prepare to teach AI.

Information Retrieval. Christian educators can prepare to teach students how to effectively use AI as a research tool in a God-honoring way. This includes studying questions like:

- What type of research is AI suited for? What type of research is AI not suited for?

- What are the most effective ways for setting up an effective AI-based information query?

- How can we practice AI-based retrieval methods in a way that aligns with and even strengthens our God-given intelligence?

Information Evaluation. It is imperative that Christian educators teach students how to evaluate bot-generated content, especially when that content reflects certain worldviews and agendas that may not be obvious on the surface. This would include exploring questions such as:

- How are neural networks produced and how do they function? How should this inform evaluation of bot-generated content?

- What are the best practices for fact-checking auto-generated content?

- Do chatbots reflect the secular worldview of their human programmers? If so, how can we engage with auto-generated content without being naïve or unnecessarily dismissive?

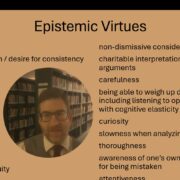

- What epistemic virtues are important when performing due diligence on material produced by a chatbot?

Information Behavior. Christian educators can prepare to teach students to work with bot-generated content in a way that is consonant with the goals of Christian education. This includes addressing questions like:

- Is it ever appropriate for students to incorporate bot-generated content into a writing project? What about getting a bot to help produce an outline, or edit a draft?

- Is it plagiarism or cheating to take bot-generated content and rewrite it in one’s own words?

- When we have identified that bot-generated content is reliable and helpful, how do we avoid merely mimicking it instead of synthesizing it into larger schemas of personal knowledge?

Information Habits. Christian educators should prepare to teach students the types of habits constitutive to flourishing with bot-generated content. This would include questions like the following:

- What are the primary temptations when using AI as an information retrieval tool, and what habits help buffer us from these temptations?

- What epistemic virtues are conducive to good information habits when working with AI?

- What types of offline behaviors help one to be virtuous when interacting online with AI?

To address these questions, students need more than simple instruction on information literacy; rather, they should be guided to perform exercises on systems like ChatGPT, Bard, Bing, etc. That is where bringing these systems into the classroom becomes imperative. This will give students the opportunity to see that different bots give different answers, that bots are not worldview-neutral, that bots can be helpful for certain types of queries but downright misleading for others. (See my earlier article on philosophical bias in ChatGPT.) Students can also be guided to reflect on the character traits necessary for performing due diligence on bot-generated content with virtue and wisdom. There is, in fact, no end to the types of exercises Christian educators can do with chatbots in the classroom.

Conclusion

To return to my earlier question, should we bring ChatGPT into the classroom? Not if we are using it as a substitute for writing and reasoning. But to teach next-generation research skills and information literacy – absolutely.

I will go even further: the consequences of not teaching AI-based information literacy will leave our students defenseless against the type of demoralization that Bezmenov warned about.

We are in the midst of an intensifying epistemological crisis. Christian teachers, get ready.

This article originally appeared in my column at Salvo Magazine and is reprinted here with permission.