For eighteen years, Dr. Manette had been imprisoned in the Bastille, during which time he progressively descended into a state of chronic depression. The trauma of almost two decades of solitary confinement eventually resulted in Dr. Manette losing his mind and becoming merely a shadow of his former self. Upon his release, the doctor’s senses gradually returned to him under the gentle care of his daughter, Miss Lucie Manette. Even after being restored to health, however, he continued to struggle against the fruit of his long captivity, a struggle that involved occasional relapses. Throughout his quiet and relentless struggle, the doctor was completely absorbed with serving his family and friends, and even risking his life to meet their needs.

One evening, Dr. Manette’s elderly friend, Jarvis Lorry, came upon the doctor sleeping. Even in sleep, Mr. Lorry could see the effects of the doctor’s long struggle to remain mentally and emotionally healthy:

“Into his handsome face, the bitter waters of captivity had worn; but, he covered up their tracks with a determination so strong, that he held the mastery of them even in his sleep. A more remarkable face in its quiet, resolute, and guarded struggle with an unseen assailant, was not to be beheld in all the wide dominions of sleep, that night.”

In Dr. Manette, the battle to remain mentally and emotionally healthy was a colossal struggle. In this regard, Dr. Manette is like each one of us. Each of us face the same set of choices that he did: will we let our mind and heart be defined by the wounds we’ve suffered, or will we struggle against these assailants in order better to serve those God has placed in our life? It is in these choices that we have the power to either realize our true self, or be merely a shadow of the person we were created to be.

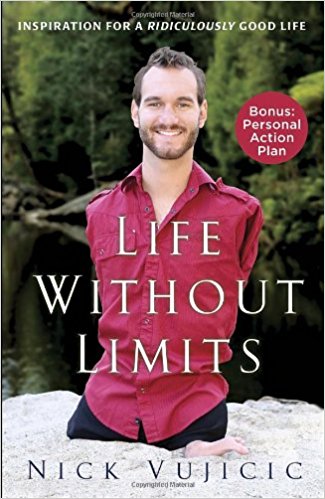

Dr. Manette is a fictional character, but the annals of real life furnish us with examples of individuals who are just as courageous in battling against inner negativity in order to realize their true selves. One example is Nick Vujicic, an Australian who was born without any limbs (no arms and no legs).

If anyone had a reason to descend into self-pity and despair, Nick did. Throughout his boyhood Nick was subject to constant bullying. He had nothing to look forward to except a life of hopelessness. At age eight Nick thought about committing suicide, while at age ten he tried to drown himself.

Observing Nick today, one would never suppose that he used to struggle with depression and hopelessness. Today he has an amazing ministry as a motivational speaker and evangelist.

Nick’s transformation began when he determined to reframe his life in positive terms. He learned to focus on the blessings he did have instead of grumbling about what he was forced to do without. Today as he travels throughout the world, Nick tells people that no suffering—regardless of how severe—has the power to rob us of the choice to embrace contentment, hope and joy. As he shared in a 2012 talk for TedX,

“We’re all looking for hope. Hope you can’t just have just because you were born with hope. No, we’re born with pain. We’re born and live through difficulties. In our life my parents always taught me that even though we don’t know why I was born this way, that we have a choice: either to be angry for what we don’t have, or to be thankful for what we do have.”

Doing What Comes Naturally

There is a notion in our culture that “being true to yourself” involves doing what comes naturally, as if virtues that arise after a process of struggle are somehow contrived and artificial. According to this widespread assumption, the best we can do is be like Elsa in the Disney film Frozen: stop trying to be the good girl everyone expects you to be, since the path to true redemption lies in learning to “let it go” and be yourself—to realize the authentic person you are inside. According to this narrative, authenticity is often associated with pursuing the path of least resistance as a person follows impulses, habits and personality traits that come spontaneously. The implication is that spending years to develop habits and dispositions that are hard work is somehow repressive, hypocritical and less “true to yourself” than following your natural impulses.

Nick Vujicic’s testimony contradicts this view of the self. The joyful love-filled person he has become did not arise naturally. He had to work at it, just like Dr. Manette had to master the unseen assailant that threatened to pull him back into the darkness. Left to his natural impulses, Nick would have continued the downward spiral of envy, self-pity and despair that characterized his early boyhood. But gradually Nick trained himself to have a different attitude towards life. In his book Life Without Limits, Nick shared how this struggle involved monitoring his thoughts, constantly battling dark thoughts and negative feelings. By retraining his attitude, Nick was able to realize God’s plan for his life and discover his true self.

Retraining our outlook on life in the way Nick Vujicic did is rather like trying to learn a foreign language. When someone first begins learning a new language, the new words and grammar may feel strange and unnatural, and it’s easy to slip back into one’s native tongue. It takes a long time, and lots of hard practice, before a person feels comfortable with the new language. However, if the person perseveres long enough, eventually the new way of talking begins to feel natural. Similarly, when we retrain our outlook on life, it often takes a long time before the new attitudes begin to feel normal.

It is our choices—the thousands of tiny decisions we face every day—that ultimately determine what attitudes and behavior comes to feel natural to us. The theologian Tom Wright talked about this principle when Trevin Wax interviewed him about his book After You Believe: Why Christian Character Matters. Wright explained that there is something to be said for “doing what comes naturally”, but only when we appreciate that what comes naturally to each person is the result of thousands of small choices over many years.

“…for many in the West, all that matters is ‘doing what comes naturally’. That is an attempt to acquire instantly, without thought or effort, what Christian virtue offers as the fruit of the thought-out, Spirit-led, moral effort of putting to death one kind of behavior and painstakingly learning a different one…. I remember Rowan Williams describing the difference between a soldier who has a stiff drink and charges off into battle waving a sword and shouting a battle-cry, and the soldier who calmly makes 1,000 small decisions to place someone else’s safety ahead of his or her own and then, on the 1,001st time, when it really is a life-or-death situation, ‘instinctively’ making the right decision. That, rather than the first, is the virtue of ‘courage’.”

The same principle applies to other virtues besides courage, including the virtues that Paul mentioned in his discussion of the fruits of the spirit in Galatians 5. The apostle wrote that “the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, longsuffering, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control.” (Galatians 5:22-23) What are the means the Holy Spirit uses to cultivate these virtues in our hearts? Part of the answer is found in one Paul’s first letter to the Christians in Corinth. When discussing the freedom we have in Christ, Paul declared, “But I discipline my body and bring it into subjection, lest, when I have preached to others, I myself should become disqualified.” (1 Corinthians 9:27) In the Greek text, Paul is literally saying that he pommels [upopiazo] his body [soma] to subdue it. In the Greek lexicon the word “pommel” means “to strike one upon the parts beneath the eye; to beat black and blue, hence to discipline by hardship, coerce.” The word for body is “soma,” referring to the body itself, rather than the word for the “flesh,” or “old man,” which is “sarx.” Since even after his conversion Paul found the spiritual life hard work (Romans 7: 15-19), his spiritual struggle is compared to “pommeling” his body in order to receive the prize and not be disqualified. We even see this in the example of Christ Himself who, on the night in which he was betrayed, struggled to embrace the Father’s will. Developing the fruit of the Spirit is a struggle! But the good news is that the more we engage in this struggle, the more natural these virtues becomes to us.

As we read about Christian heroes and saints who instinctively did the right thing in extraordinarily difficult circumstances, and who endured martyrdom and even torture with extraordinary heroism, we mustn’t imagine that they were just naturally good, or that they had stronger willpower than you and me. On the contrary, great acts of heroism are usually the culmination of a life of thousands of small choices. The way to develop the type of love that is strong enough to sacrifice your life for somebody else is to spend every day sacrificing your own needs and desires to serve those God has placed in your life. The way to remain patient in the midst of severe persecution is to begin practicing patience in ordinary life with sundry annoyances. The way to remain grateful in the midst of severe suffering is to begin practicing gratitude for the mild inconveniences that disturb us every day. It is through these choices that we either become our true selves, or just a shadow of who we were meant to be.

How to Be True to Yourself

But what does it even mean to find your true self? It is on this point that there exists much confusion.

A walk through the mall might suggest that our true self lies in having the right material possessions. Various movies and television shows implicitly suggest that we need a soul-mate in order to become fully ourselves. Still others suppose that the price tag to self-actualization lies in a successful career, the good opinion of others, or achieving a level of wealth, fitness, education or leisure time. Accordingly, the modern self has come to be an incredibly fragile self, since our fundamental identity hinges on a constellation of mercurial conditions. The fragility of the modern identity ushers us into a life of constant stress, which the Christian psychologist, Raymond Lloyd Richmond, compares to the stress a dragon might feel guarding its treasure:

“As long as you derive your identity from the world around you, you have to be concerned about losing it. Like a dragon sitting greedily on its hoard of treasure, your entire being will be caught up in defending what you are most afraid to lose…. So the more you let go of your ‘identity’—the more you die to yourself in perfect humility—the less you have to defend; and the less you have to defend, the less reason you have for anger.

“From all the things that appeal to us in the world, we create images of how we want to see ourselves, and then we set about making ourselves ‘seen’ in the world so our images can be reflected back to us through the desire of others. Whether it’s business suits or purple hair and pierced lips, an image is an image. Some persons desire to be desired with such desperate intensity that you can actually see in their eyes the inner emptiness they seek to fill.

“You might go to great expense to project an image into the world. You might explain yourself in endless detail to others so they will get the ‘true’ picture of you. You might offer your identity to the world as if it were a bowl of jewels. But you’re offering only a plate of stones.”

To tell if you are living out of your true self or your false self, ask yourself the following question: what do you need in order to be truly you, to be able to express who you actually are? If the answer is that you need anything of this world before you can be truly you, then there is a good chance that your true self may have been hijacked by your false self (also known as the ego-self). For many Christians throughout the centuries this has meant physical death through martyrdom. But regardless of whether we are called to face martyrdom, we are all called to die to the false self—the self that needs the things of this world to survive like a car needs gasoline. Sometimes the Lord strips us of all the props we use to support our sense of self precisely so we can come to the point of anchoring our identity in Him alone (1 Cor. 2:2). Even good things (being useful for others, being appreciated by our family members or colleagues, being needed, having an intimate relationship) can all become idols when we begin defining our sense of self by these conditions.

The paradox of Christianity is that we find our true self, not by grasping good things for ourselves, but by giving our self away (Luke 9:24). The message of the gospel is that we become more truly ourselves when we strive to fulfil the needs of others, preferring other people’s wellbeing to our own (Romans 12:10; Matthew 20:16). This is what Nick Vujicic learned through his struggles growing up without any arms and legs. He learned the Biblical truth that the secret to finding yourself is to pour everything you have into serving others. In Life Without Limits, Nick talks about the importance of self-love and self-acceptance, but then adds how true self-love involves giving yourself as a sacrifice to others.

“The kind of self-love and self-acceptance I’m advocating is not about loving yourself in a self-absorbed, conceited way. This form of self-love is self-less. You give more than you take. You offer without being asked. You share when you don’t have much. You find happiness by making others smile. You love yourself because you are not all about yourself. You are happy with who you are because you make others happy to be around you….

“When Jesus was asked to name the most important commandments, he said the first was to love God with all your heart, soul, mind and strength, and the second was to love your neighbor as yourself. Loving yourself is not about being selfish, self-satisfied, or self-centered; it’s about accepting your life as a gift to be nurtured and shared as a blessing to others.”

Nick believes that modern society continually lies to us about what constitutes human flourishing. We are led to imagine that “we need to have a certain look, a certain car, and a certain lifestyle in order to be fulfilled, loved, appreciated, or considered successful.” Although this may be a particularly modern problem, throughout history humans have struggled with the temptation to view the good life in terms of temporary goods, especially food, sex, power and wealth. These temptations lure us away from the reality that ultimately, the only thing you need to be fully you is God Himself.

When we begin living in the reality that all we need for our ultimate wellbeing is Christ Himself, then the good things of this world can move us closer to Him as we can see all that is good, true and beautiful as a shadow of His beauty and love. But also, by living in the reality that Christ is enough for our ultimate wellbeing, then when the good things of this world are taken away from us—whether through suffering or voluntary self-denial—that too propels us on the journey toward Him. As we journey closer to Christ, we similarly journey closer to becoming more truly ourselves. The Christian thus finds himself in a win-win situation.

Often Christians wrongly conceive the spiritual life as if it were a type of “zero-sum game” between God and ourselves. A “zero-sum” transaction is when the gains of one side are correlate to losses on another side. It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that the spiritual life is like this, that what we give to God is that much less left-over for ourselves. I know I used to think of the spiritual life in this way. Although I would never have expressed it as such, I essentially thought something like this: In order to flourish, I need good things of this world. But God gives me rules to follow that sometimes get in the way of me being able to live a fulfilled life. I have to obey these rules because I don’t want God to get upset at me, and more fundamentally because it is simply right to do so. But these rules often stand in the way of being able to flourish and achieve full well-being. Through reading the Church Fathers, especially St. John Chrysostom (c. 349–407), I began to see things differently. Instead of conceiving the spiritual life as a zero-sum transaction, St. John Chrysostom challenges us to see virtue as something that actually enables us to become more fully human, in order to plug back into our Life-Source so we can flourish as we were originally intended. God’s commandments are not mere prohibitions preventing us from fully flourishing in our humanity; rather, they provide insight into the very nature of what it means to live, love and function as rightly ordered human beings. God’s commandments are life-giving (Psalm 118) because they show us how to become more fully ourselves.

Understanding the spiritual life in this way changes how we think about sin and idolatry. An idol is not something that simply tempts us to sin; the real problem with idols is that they present rival images of human flourishing. An idol captures our imagination with an image of the Good Life that is not rooted in Jesus Christ. When sin happens, it is often because we have first believed the lies our idols have told us about what actually constitutes a flourishing human life. For example, in the book of Exodus when the children of Israel were on their way to the Promised Land, they were enticed with the memory of the pots of meet in Egypt. When they rebelled against Moses, this was because their hearts had first believed the lie that Egypt, not the Promised Land, is where they could truly flourish. In our world, we are bombarded with an endless array of enticements that present rival visions of human flourishing. Whether these rival visions of flourishing come from television commercials, glossy magazines, or the local mall, they attack us at a gut-level, inculcating in our imagination the notion that wellbeing lies in material possessions, or youth, or vitality, or sex, or food, or popularity, or beauty, or having sufficient space to express our individuality.

The issue is not that the good things of creation are bad, but that we get cheated when we see the Good Life being defined by these things, rather than being defined by union with Christ. I love how John Piper discusses this in Desiring God, and also C.S. Lewis in various places throughout his writings. Both these authors have followed St. Augustine in showing that all idolatry is a misfiring of the heart’s basic orientation to hunger after God. Our underlying spiritual problem is one of disordered love. Listed to the way Piper describes this principle in his book A Hunger For God:

“The greatest enemy of hunger for God is not poison but apple pie. It is not the banquet of the wicked that dulls our appetite for heaven, but endless nibbling at the table of the world. It is not the X-rated video, but the prime-time dribble of triviality we drink in every night. For all the ill that Satan can do, when God describes what keeps us from the banquet table of his love, it is a piece of land, a yoke of oxen, and a wife (Luke 14:18-20). The greatest adversary of love to God is not his enemies but his gifts. And the most deadly appetites are not for the poison of evil, but for the simple pleasures of earth. For when these replace an appetite for God himself, the idolatry is scarcely recognizable, and almost insurable.”

The Path to the True You

“We become what we love” writes Dr. Caroline Leaf, who has spent over thirty years studying the brain, both in clinical practice and as a neuroscience researcher. Her fascinating work testifies to the Biblical truth that we can change who we are—both on a spiritual and physiological level—by what we love and what we choose to focus our attention on.

In her book Switch on Your Brain, Leaf shares recent discoveries in neuroplasticity which have established that “as we think and imagine, we change the structure and function of our brains…. Our brain is changing moment by moment as we are thinking. By our thinking and choosing, we are redesigning the landscape of our brain.” A similar process occurs at the level of DNA and epigenetics, whereby DNA can “change shape according to thoughts and feelings.”

Leaf cited one study conducted by the Institute of HeartMath which revealed that “when we make a poor-quality decision—when we choose to engage toxic thoughts (for example, unforgiveness, bitterness, irritation, or feelings of not coping)—we change the DNA and subsequent genetic expression, which then changes the shape of our brain wiring in a negative direction.” But the same study also held out hope of healing for those whose brains have been ravaged by toxic thoughts: “the most exciting part of this study was the hope it demonstrated because the positive attitude, the good choice, rewired everything back to the original healthy positive state. These scientists basically proved we can renew our minds.”

Leaf’s research shows that by consciously choosing to renew your mind and engage in acts of metacognition (watching your brain to weed out toxic thoughts) you do more than simply build a healthier brain for yourself: you also become the “Perfect You.” The Perfect You is the particular reflection of the image of God that is unique to you, what C.S. Lewis called “a curious shape…made to fit a particular swelling in the infinite contours of the divine substance.”

The “Perfect You” can be sabotaged if you let false images of the self—rival visions of the Good Life—pull you away from your vocation to reflect God’s glory in your unique and individual way. As Leaf explains in her book The Perfect You: a Blueprint for Identity,

“We will become whatever we focus on the most. The Israelites exchanged their glories (their Perfect You as image bearers of God) for the image of the golden calf, and we too can lose ourselves trying to be what we are not called to be (Exod. 32:4; Rom. 1:18-25). We become what we love, so we must learn to love our God by seeing his incredible piece of eternity inside of us.”

Sometimes the idols that lure us away from realizing our own “Perfect You” can be something as seemingly benign as comparing ourselves to others instead of being content with the unique person God created us to be. For example, think back to Nick Vujicic—the Australian born with no arms and no legs. If he had continued to compare himself to others, defining the blueprint for his life by other people’s abilities, he would not now be reaching tens of thousands of people with the message of hope and salvation. It was when Nick made the choice to accept who he was, independent of all external condition and obstacles, and to use who he was to serve others, that he began the journey of self-realization.

Further Reading

“The kind of self-love and self-acceptance I’m advocating is not about loving yourself in a self-absorbed, conceited way. This form of self-love is self-less. You give more than you take. You offer without being asked. You share when you don’t have much. You find happiness by making others smile. You love yourself because you are not all about yourself. You are happy with who you are because you make others happy to be around you….

“The kind of self-love and self-acceptance I’m advocating is not about loving yourself in a self-absorbed, conceited way. This form of self-love is self-less. You give more than you take. You offer without being asked. You share when you don’t have much. You find happiness by making others smile. You love yourself because you are not all about yourself. You are happy with who you are because you make others happy to be around you….