The philosophy behind Common Core goes back to one of the greatest educational reformers of the twentieth-century, the pragmatic psychologist B.F. Skinner (1904-1990). Skinner took the factory mindset of American pragmatism and applied it to school children, dehumanizing them in the process. Skinner was to the classroom what Frederick Winslow Taylor had been to the factory.

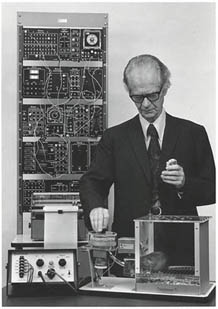

Skinner is famous for inventing the prototype of the Skinner Box, an operant conditioning chamber to study animal behavior. But Skinner didn’t stop at rats and mice: he wanted to take what he learned from rodents and apply it to the education of American school children. (Skinner acknowledged no ultimate distinction between men and animals, having declared “To man qua man we readily say good riddance.”) He wanted, in his own words, to bring “the results of an experimental science…to bear upon the practical problems of education.”

Skinner is famous for inventing the prototype of the Skinner Box, an operant conditioning chamber to study animal behavior. But Skinner didn’t stop at rats and mice: he wanted to take what he learned from rodents and apply it to the education of American school children. (Skinner acknowledged no ultimate distinction between men and animals, having declared “To man qua man we readily say good riddance.”) He wanted, in his own words, to bring “the results of an experimental science…to bear upon the practical problems of education.”

In his 1984 essay ‘The Shame of American Education,’ Skinner delighted that “with teaching machines and programmed instruction one could teach what is now taught in American schools in half the time with half the effort.” (Like Frederick Taylor, Skinner seems to have also been haunted with the idea of a time deficit.)

The same principles that applied to teaching children also applied to animals, leading Skinner to boast “I could make a pigeon a high achiever by reinforcing it on a proper schedule.”

Echoing the hyper pragmatism of Frederick Taylor, Skinner evacuated all questions of ultimate meaning from consideration and applied himself only to the question “What works?” He cared little about finding ways for human nature to flourish, nor did he care about finding ways to help draw the soul of students towards a love for the good, true and beautiful. (Skinner believed that both human nature and the soul did not exist). Rather, what mattered was facilitating what he called “cultural engineering” by “programming” students to become the type of citizens that would help contribute to a better society, conceived in collectivist terms.

Before we can appreciate Skinner’s influence on Common Core, we must consider the type of education Common Core presents and how this contrasts with how education has traditionally been understood.

In laying out their standards, the architects of Common Core have spoken candidly about what they see the goal of education to be, and it is not education at all, but training. What our elites want from the next generation is not better humans but better workers, and Common Core offers the environmental conditioning for achieving this.

This differs greatly with traditional classical education. America’s founders understood that a healthy democracy requires that citizens learn to think critically, to ask questions and to be endowed with a well-ordered reason and imagination. It was a vision of education that Tracy Lee Simmons has described as being able to preserve the riches of our cultural heritage through “inculcating the ways of sound thinking.” This was the same vision articulated by Plato, who argued in The Republic that the highest goal of all education is knowledge (by which he means a deep acquaintance with) the Good.

By contrast, when the architects of Common Core came to trying to describe the goal of education, they found themselves unable to rise any higher than “college and career readiness” and “21st century literacy” for a “global economy.” To them, students are little more than units for a future workforce in the mad scramble for America to compete with emerging economies like China and India. AsEmmett McGroarty and Jane Robbins warned on the Catholic Vote website, Common Core “is a workforce-development scheme that treats the individual as human capital, to be shepherded where needed in aid of a centralized, corporatist economy. Schools are factories where children are trained, and the teachers are their supervisors.” The cultivation of the soul that Aristotle and Plato understood to be the proper focus of education gets lost beneath Common Core’s political agenda and its exclusive focus on the itemization of skills.

I suspect Skinner would be pleased with this, as he eschewed the classical and Christian vision of enlarging human experience by pointing to realities higher than human experience, believing there is nothing higher than human experience to inspire our ethical endeavours. He was one of the signatories to the Humanist Manifesto II, which states that “moral values derive their source from human experience. Ethics is autonomous and situational needing no theological or ideological sanction.”

In the following post in this series, I will show how the pragmatism of Common Core assaults the imagination.

Further Reading