Last week, on Monday November 22nd, a 187-year-old statue of Thomas Jefferson was removed from the New York’s City Council chamber. A crew took down the 884-pound statue after the council unanimously voted that it had to go. Council member Inez Barron expressed the consensus by saying Jefferson should not be in “a position of honor and recognition and tribute.”

As the author of the Declaration of Independence and a key progenitor of American conceptions of liberty, Jefferson holds enormous significance for the United States. His removal from New York City, together with calls to dismantle the Jefferson Memorial, are symbolic of the left’s abandonment of classical liberalism, and the unraveling of the liberal order on which America is based.

The Religious State as the Problem

To understand the classical liberalism represented by Jefferson, we have to go back to the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648). This deadly dispute, which saw a greater percentage of European deaths than WWII, brought the religious conflicts of the previous century onto the battlefield. Even after the war ended with the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, religion continued to be the single most polarizing political problem for Europeans.

Well before the close of the 17th century, war-weary Europeans were ready for something new. This set the stage for various philosophers in the 18th century (Voltaire, Diderot, Rousseau, etc) to agitate for the separation of religion and politics. Thus was born the idea of the modern idea of the secular state.

The Secular State as the Solution

In popular language, “secularism” has come to be virtually synonymous with anti-religion. But when historians use the term, they are referring to the practical outworking of the aforementioned political philosophy which maintains that government should be neutral towards religion.

Voltaire incapsulated the idea of the secular state in his little book Letters on the English. While exiled in England during the years 1726 and 1729, Voltaire had been impressed by what he saw, which was very different from his native France. Voltaire wrote his Letters to educate the French on what they could learn from England.

In Voltaire’s sixth letter, he turned his attention to London’s Royal Exchange, which was the 18th century’s equivalent of Wall Street. Significantly, Voltaire saw the market as England’s true religion, a place where people of all nations and denominations “meet for the benefit of mankind.” For Voltaire, the commercialized state—as embodied in the Royal Exchange—offered hope, since it was here that the practitioners of various private faiths could come together for the public good of economic exchange.

For Voltaire, relativism in religion and secularism in society were solutions to the protracted religious wars that had plagued Europe since the Reformation. A state structured around the new religion of buying and selling would enable Jews, Muslims, and the various Christian sects to put aside their hatred of one another and unite in a common cause. In the Royal Exchange, all religious believers could adopt a neutral position, interacting towards a common goal.

The basic idea—that the private economy of religion contrasts with the public economy of the market—has become the hallmark of modern secularism. Secularism is quite tolerant of religion, as long as the latter stays in its lane, leaving public life to be defined by the liturgies of the market. But if the state and its economic transactions should be neutral towards religion, should they also be neutral towards virtue?

The Secular State and the Privatization of Virtue

Throughout the 18th century, virtue followed the itinerary of religion in becoming increasingly privatized. In his book Heavenly Merchandise: How Religion Shaped Commerce in Puritan America, Mark Valeri showed that by the 1740s and 1750s, American clergy and merchants alike had come to see virtue, not in terms of the goodness of certain actions in the visible world, but in terms of invisible inner qualities. Over the course of the 18th century, New England merchants reconstituted their moral languages so that by mid-century, pious merchants worried about the corruption of personal inclinations yet expressed no reservations about business practices of which their Puritan ancestors would have disapproved. By the early nineteenth-century, virtue had collapsed almost entirely into a matter of domesticity and personal interiority, what historian Mark Noll described as “a much more private quality, a standard of personal morality.”

The basic narrative came to be that the state can only concern itself with matters of economic and sociological rationality, which is a realm independent of the purely private and personal realm of virtue and morality. But because politics is inescapably teleological (oriented towards good ends), the expulsion of virtue merely created space for surrogate forms of morality to emerge disguised in the language of scientific rationalism (hence the 19th and 20th century fetish with the social sciences).

Christian communities were swept up in these secularizing processes. What Voltaire believed about the market—that Christians could leave their faith behind when they entered the Royal Exchange and operate according to the principles of religious neutrality—has not only achieved widespread acceptance, but has come to define the self-understanding of most Christians. Believers have been willing to cede to the secular the entire realm of creation, including art, education, media, law and government, agriculture, food, psychology, business, technology and innovation, etc. It is not that Christians have withdrawn from involvement in these arenas, but that the assumptions of secularism largely define the terms of their engagement. In particular, the uber-assumption of secularism—that there can be a rigid division of life into separate spheres—has been left unquestioned and unchallenged.

Classical Liberalism and Secularism

The theory of the secular state is closely related to the idea of Classical Liberalism. At the risk of oversimplification, Classical Liberalism is a political philosophy prioritizing the rights and liberties of the individual. Classical liberalism was opposed to despotic forms of rulership and favored governments structured along constitutional and republican lines. Classical Liberalism served as the impetus for the collapse of nearly all the European monarchies from the late 18th to the 20th century, which gave way to various forms of self-government rooted in the logic of maximal autonomy.

In addition to advocating principles such as limited government, representation, and civil liberties, classical liberals joined Voltaire in looking favorably upon secularism, on the assumption that religious liberty can best be preserved by a government that does not interfere in spiritual matters. Thus, Classical Liberalism is closely wedded to secular notions of religious neutrality as a means for securing the autonomy of citizens and preventing a repeat of the 17th century wars of religion.

The American system was formed at the intersection of secularism, Classical Liberalism, and Christianity. While various founding fathers held a range of views on the relationship between religion and politics, none encapsulated the secularist strain better than Thomas Jefferson. In his 1785 text Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson declared that previous Christian forms of government created “religious slavery,” insofar as “the operations of the mind, as well as the acts of the body, are subject to the coercion of the laws.” He went on to specify the necessity of government remaining religiously neutral:

“The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others. But it does me no injury for my neighbour to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.”

The American system came to embody the spirit of Jefferson’s Notes, especially the concern that statecraft should be a realm of spiritual neutrality. This can be seen in the fact that the Constitution made no appeal to God, not even a rhetorical one, even though the Articles of Confederation and the Declaration had. The Constitution also prohibits any religious test for office, despite the fact that it was widely accepted at state-level that atheists could be excluded from public office. The significance of these moves is not that the Constitution embodied irreligious sentiment so much as that it reflected an attempt to achieve the ideal of a value-neutral state, or what Alasdair MacIntyre called “the privatization of the good.”

In the two hundred years since the Constitution, the theory of the value-neutral state has become the taken-for-granted background for thinkers on both the left and the right. In the last gasp of the theory’s credibility, it received a gallant recapitulation in the writings of British political theorist Michael Oakeshott (1901-1990). Oakeshott’s hugely influential 1947 essay, “Rationalism in Politics,” rewrote Burkean conservatism for a 20th century context, retaining Burke’s practical wisdom but stripping it of the latter’s teleology, reconfiguring it within a value-neutral context. In Oakeshott’s model of “liberal conservatism,” politics is essentially adverbial: it cannot tell us what ends to pursue, it can only tell how individuals should pursue their own private ends. Contra ancient tradition, both classical and Christian, statecraft is not oriented towards the Good or any substantive notion of human flourishing, and thus it collapses into a closed system with no goal, no final principle, and no destination. Oakeshott famously described this by asserting that,

“In political activity . . . men sail a boundless and bottomless sea; there is neither harbour for shelter nor floor for anchorage, neither starting-place nor appointed destination. The enterprise is to keep afloat on an even keel; the sea is both friend and enemy, and the seamanship consists in using the resources of a traditional manner of behaviour in order to make a friend of every hostile occasion.”

It is not clear how the political enterprise can even achieve coherence if there is no acknowledged end or goal towards which human society is oriented. But this is precisely the paradox of attempting to construct a political order on value-neutral premises. To pursue the common good independent of any conception of the Highest Good is to collapse the political enterprise into self-referentiality.

The Collapse of Secular Classical Liberalism

From our historical vantage point in the 21st century, it is easy enough to deconstruct the cluster of assumptions behind Classical Liberalism and its bedfellow, the secular state. It is now clear that economic exchange does not coordinate for “the benefit of mankind,” as Voltaire argued, but can be just as oppressive and divisive as religion. And few people would still view commercialism in such a positive light as Voltaire (who, after all, was writing before the dehumanizing factories of the industrial revolution).

It has also become abundantly obvious—contra Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia—that there is no religiously neutral idea of religious neutrality. The very attempt of secular governments to delineate what constitutes “religion,” and to keep “religion” thus defined separate from “politics,” cannot be undertaken without, at some level, smuggling in certain metaphysical and even spiritual assumptions. For example, before a secular state can presume to be neutral towards religious questions, they must first have some idea what religion is, and what space is properly the province of the spiritual; but the definition and scope of religion is not a non-religious question, and there is no way to address this problem without, at some level, taking sides—whether explicitly or implicitly—on a range of theological issues.

But even apart from questions of coherence, the theory of religious neutrality has proved unworkable, since a state that assumes authority over religion, even in the limited context of defining and demarcating the latter’s scope, will not be above policing beliefs deemed to be incompatible with secularized notions of the good life. We saw this begin playing out in America during the second half of the twentieth century, when the space allowed for religion in public began steadily to shrink.

It has also become clear that the fiction of a value-neutral state merely created conceptual space for surrogate forms of morality to emerge, such as what we are seeing now with recent calls from progressives to use the strong arm of government to enforce a new pantheon of “woke” virtues.

It has also become clear that the classical liberal emphasis on self-government is quickly collapsing into a much broader ideology of atomized individualism, in which the state must underwrite individualism through validating personal desire. This is both deeply oppressive and deeply unsatisfying. It is oppressive in this way: as the logic of maximal autonomy is increasingly applied not just to citizenry in the aggregate (i.e., the right of citizens to elect their rulers, for example), but to individuals and their lifestyle choices (i.e., the right of citizens to have their personal desires secured by the state), society is reduced to a zero-sum contest between winners and losers. As Sohrab Ahmari put it in a much-discussed 2019 article, the logic of maximal autonomy requires society to give as wide a berth as possible to anyone wishing to redefine what is good, true, and beautiful, even if that means creating a society that is deeply unsatisfying and unfree.

But a state that presumes the vocation of underwriting personal desire becomes not only oppressive, but deeply unsatisfying, for it perpetuates the conceit that we can ignore the roles of non-governmental institutions (family, church, fraternity associations, neighborhoods, guilds) inescapably play in human flourishing. We saw this conceit on full display with President Obama’s “The Life of Julia” campaign, which walked us through a fictional woman’s life, from birth to death, showing how government-dependence enabled Julia to achieve a near fairy-tale existence without reference to any relationships or community (with the exception of a “community garden”). If any good has come out of the rise of identity politics and tribalism, on both the right and the left, it has been to expose the vacuity of atomized individualism, reminding us that humans are inescapably communal creatures.

What Next?

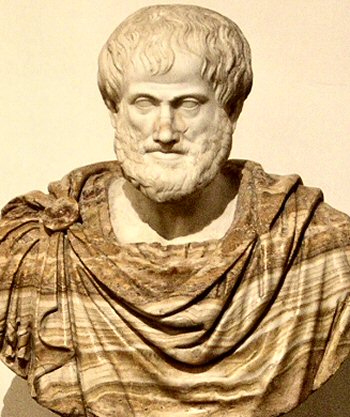

Classical Liberalism was like a marriage you know will eventually end in disaster, yet you genuinely wish it well. Maybe you even want to try to patch things up for as long as possible because you know the inevitable unravelling will be messy. Thomas Jefferson is an important figure in this heroic attempt to keep Classical Liberalism together. He represented all that is best, bad, and inconsistent in the secular liberal order, including a kind of fragile stability: a place where the left and the right, Edmund Burke and Thomas Paine, David Barton and Barack Obama, could all come together in a type of fragile synthesis. But the Jeffersonian synthesis is quickly breaking down.

It is not clear what will replace the classical liberalism on which America was based. It is not clear whether the United States can even survive the collapse of the Jeffersonian synthesis. And it is not clear what philosophy or set of principles conservatives should adopt as the old tropes of Classical Liberalism are disintegrating.

Sohrab Ahmari, op-ed editor of the New York Post and a former editor at the Wall Street Journal, would have us move away from small-government conservatism and leverage the power of the state to crush progressives, even if it means abandoning the procedural norms of liberal democracy. Ahmari joins Harvard’s Adrian Vermeule in advocating “integralism,” a political philosophy in which the state is, in some sense, subordinated to the Catholic Church.

Other thinkers, like the political commentator David French and many associated with The National Review, would like to continue the legacy of conservative “fusionism” by working within the framework of the secular liberal order. This means mounting what French calls a “zealous defense of the classical-liberal order,” while using the arguments and conventions of the secular state to defend socially conservative values. The neoconservative political writer, William Kristol, incapsulated the vision of this synthesis when he called for “a new conservatism based on old conservative—and liberal—principles.” This fusion of liberal and conservative principles is also a feature of figures like the Missouri Republican Senator Josh Hawley, whose folk conservatism draws on the legacy of Rousseau to offer a liberal-conservatism as an alternative to progressive-liberalism.

Still others are urging American conservatives to join what they call “the new right,” or “the post-liberal right” modelled on Viktor Orbán’s Hungary and its open renunciation of democratic norms. This is the position of Rod Dreher, who spent four months in Hungary on a fellowship from the Danube Institute and now recommends that America should adopt the Orbán model.

As conceptual space is opening up to move beyond the procedural norms of liberal democracy, how far are thinkers on the post-liberal right willing to go? This is not clear, but their thought is increasingly peppered with rhetorical appeals to militancy that remain ambiguous. Michael Anton, who served as a senior national security official in the Trump administration and is now one of the leading thought-leaders in the post-liberal right, had a two hour conversation with Curtis Yarvin last May in which plans were discussed for how an American Caesar could seize dictatorial powers.

Meanwhile, the conservative populace is willing to invoke militancy without any of the rhetorical ambiguity of their thought leaders, as evidenced by a recent poll from American Enterprise Institute found that 4 in 10 Republicans say political violence may be necessary. This number is likely to increase as there emerges a growing contingent of younger conservatives who are as disaffected with the political status quo as they are with traditional religion. Many of these young people on the right are turning towards the type of Nietzschen solutions advocated in the wildly popular self-published book Bronze Age Mindset.

For Patrick Deneen, Professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame, the answer lies in returning to the conservatism of figures like Burke and Disraeli, but rooted in the Aristotelian concept of the human person. In an interview last year with Yoram Hazony, Deneen said that Burke’s response to the Enlightenment’s political project provides a template for a conservatism that moves beyond the folk conservatism that is “really just a variant of liberalism.” Deneen echoed Ofir Haivry and Yoram Hazony who wrote a 2017 piece calling for a renaissance of pre-liberal Anglo-American conservatism.

It may be that all such questions prove to be purely academic, as events outside our control begin rapidly to unfold. But one thing remains certain: there can be no going back to the secular liberal order of Jefferson. Statues and monuments will continue to fall, and the secular liberal order will continue unraveling. But let us not go gently into the coming night. After all, it was an heroic experiment.